Markman Ellis introduces his talk for the Immigrants of Spitalfields Festival – ‘A Tea-Drinking Nation: How Britain Came to Identify with a Migrant Alien in the Early Eighteenth Century’ on Monday 20th June 3pm, Hanbury Hall, Hanbury St, E1 6QR. (Click here for tickets)

Richard Collins’ ‘The Tea Party’ (c.1727), Courtesy of Goldsmiths’ Hall

Britain has been celebrated as ‘a tea-drinking nation’ since at least the late eighteenth century and a nice cup of tea remains one of life’s most comforting rituals. Tea-drinking has associations with hearth and home, and is emblematic of wider British ideas of both polite society and humble domesticity. How did this little leaf, a migrant from half-way round the world, come to such prominence in Britain?

Although tea-drinking has been almost ubiquitous in Britain for over two hundred years, tea itself is both a migrant and a relative newcomer. Tea first arrived in London in the mid-seventeenth century – too late for Shakespeare ever to have had a cuppa, for example. All tea in the eighteenth century was grown and manufactured in China and Japan. In the nineteenth century, tea growing extended to India and Sri Lanka, and later to Africa. Commercial tea plantations even exist in Britain today, but tea was at first an exotic rarity. Imported by merchants and adventurers, tea was a strange hot drink made from a pale grey-green leaf, producing a subtly-flavoured brightly verdant liquor – aromatic with grassy vegetable aromas – with the ability to aid wakefulness.

Tea-drinking was transformed in the course of the eighteenth century. At the beginning, the migrant leaf was scarce, luxurious and ruinously expensive. At up to ten pounds a pound, it was the equivalent today of about ten thousand pounds a pound. But by the seventeen-eighties – only a century later – tea was ubiquitous in Britain, retailed in every town and city with the cheapest varieties selling for a shilling a pound – still a substantial amount – but within reach of all but the poorest. Tea had become essential to the British way of life.

The East India Company was central to this transformation, just as tea was central to the East India Company. The company had begun as a corporation specializing in the importation of silk and spices from India. The trade in tea began with small and irregular parcels, sent almost as an afterthought, in the seventeenth century. But in the eighteenth century, the East India Company began to find a ready market for tea. Establishing a trading factory in Canton (now Guangzhou) in the early eighteenth century gave the Company access to a steady supply of tea and imports increased exponentially through the rest of the century.

In London, the tea was offloaded from the Company ships and stored in a series of vast warehouses near their headquarters in Leadenhall St, both those in New Street off Bishopsgate St, and those running down towards the Thames, in Crutched Friars and Mincing Lane. Some of these warehouses can still be seen in Devonshire Sq, just south of Spitalfields, though these huge buildings are Victorian replacements. The tea was sold in the vast Sales Room at East India House for distribution though the networks of tea-merchants and grocers. Moving all this tea around employed thousands of men as porters and warehouse men – tea was big business in Shoreditch.

Eighteenth-century tea was different to the beverage normally consumed in Britain today. We are now used a dark and tannic brew, which stains the water quickly, usually made from a teabag, and is consumed with milk. Early eighteenth-century tea was almost always one of various forms of green tea (with names like ‘bing,’ ‘hyson,’ and ‘imperial’). But there was also ‘bohea,’ a form of red or brown tea now identified as a Chinese Oolong tea. All tea is made from the same plant, Camellia sinensis, and the difference between kinds of tea reflects growing conditions and manufacturing process. For darker teas, the leaves are allowed to oxidize before being cured or roasted.

Being green or at most the delicate reddy-brown of an Oolong, eighteenth-century tea was usually consumed without milk. Sugar, when available, was preferred. Richard Collins’ conversation painting ‘The Tea Party’ of 1727 shows an English family taking tea at home, displaying their cultured prosperity through their elaborate display of tea-things. On their lacquered tea-tray is an English silver tea-set, comprising a teapot on a stand, a water jug, a tea canister, a sugar bowl, a pair of sugar tongs, a spoon boat with three tea spoons, and a slops or waste bowl. The mother is dressed in a lustrous black silk gown with a gold apron, with delicate lace cuffs, handkerchief and cap. Her husband relaxes in an unbuttoned shirt and a soft turban-like cap known as a ‘banyan,’ proclaiming his status as a gentleman at leisure. Sheltering under an arm of each parent is a child, with loose hair and dressed in plain clothes. The tea is consumed in fine blue and white china cups and saucers. As was conventional in this period, the teacups are without handles. The family displays the various polite ways to hold a cup of scalding hot tea. The painting depicts three Chinese commodities central to the East India Company -silk, porcelain, and tea. Even in a simple quotidian activity like taking tea, eighteenth-century Londoners participated in the globalized economy.

Collins’ painting of this unnamed English family is a kind of showing off, advertising their success as a prosperous family in the middle stations of life. Tea was the perfect emblem of their success, a status symbol at the center of a complex social ritual. When tea became British, it was associated with both luxury and good health – although it was of course a highly habit forming drug, it did not inebriate. Tea-drinking was further associated with the polite forms of sociability practiced by high-status women, especially the queen and her maids of honour.

Even when tea became ubiquitous in Britain in the second half of the eighteenth century, it retained this association with more refined forms of human interaction – with conversation, with family and with good manners. Tea-drinking seemed to express most clearly a preference for enlightened forms of social behavior, for civic values, for domestic virtue, for tolerance and kindness. Tea, even though it was an alien and exotic commodity, came to express those qualities that British people most admired about themselves.

Morning by Philippe Mercier, 1758 (Courtesy of Yale Centre for British Art)

Camellia Sinensis, engraving by J Miller, 1771 (Courtesy of Wellcome Library)

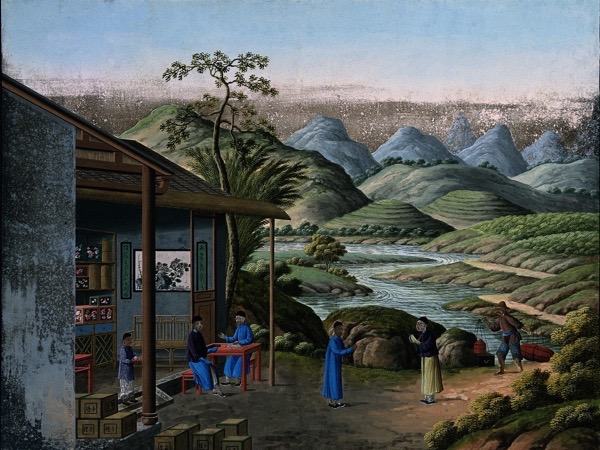

A tea plantation in China with workers packing the tea into boxes (Courtesy of Wellcome Library)

East India Company warehouses in New St, Spitalfields

Sale Room of East India House by Augustus Charles Pugin & Thomas Rowlandson from the Microcosm of London, 1809 (courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

Trade card of Robert Fogg (courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute)

Trade card of Raitt’s Tea Warehouses (courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library, Yale)

The Tea Phrensy by M Smith, 1785 (Click this image to enlarge)

Markman Ellis is co-author (with Richard Coulton & Matthew Mauger) of Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf that Conquered the World. They teach eighteenth-century studies at Queen Mary University where they blog at Tea in Eighteenth-Century Britain.