Last week, I published Steven Harris‘ candid memoir of his childhood at Great Eastern Buildings off Brick Lane and today I present his poignant account of two local shopkeepers, one universally beloved and the other notorious by reputation, yet both well-known Spitalfields personalities at that time.

Everyone I ever spoke with recalled Great Eastern Buildings in affection and, without exception, everyone also knew and loved Harry Fishman, owner of the newsagent on the corner of Quaker Street and Brick Lane. Harry was a legend in his own lifetime who commanded a significant degree of respect and reverence, even though we local kids were forever pinching comics, sweets and even small coins from his shop.

In my childhood, Harry was already in his sixties, around 5’ 8”, a bit chubby and with a receding hairline. He existed as a kindly granddad figure who seemed to have an easy-going attitude and a constant smile on his face, always avuncular and jovial, in contrast to my own granddad, Knacker, who was a mean old goat. We children felt a sense of empathy with Harry despite our small scale pilfering. He was never angry or said anything bad about anyone. Accordingly, we always looked forward to visiting his store, run down as it was. My friend Sheila Bell remembers his generosity and how, in the fifties, she would go to Harry’s, hand over her halfpenny and get a whole cone of sweets. By the mid-sixties, inflation meant our halfpennies only bought four black jacks (chewy liquorice sweets) or fruit salads (multi-coloured chewy sweets) – nothing like a coneful.

Harry was married to Marion who was short and round, and not nearly as easy going as Harry. She was far more aware of our ‘tea leaf’ tendencies and more than willing to challenge us, as Sylvie Pattern confided to me, recounting how Marion gave her a dressing down for the activity of her sons, Stephen and Keith, nicking sweets. Fortunately, Marion was not a regular presence in the shop which permitted us to benefit from Harry’s largesse, turning a blind eye to our pilfering. Though how he managed to ignore one of the local kids, Snudge, once nicking seven large bottles of pop is beyond me.

Harry even rewarded us sometimes. ‘Harris, want to do a bit of work?’ he would occasionally call out to me and whichever other kid was nearby, offering the opportunity to earn maybe a shilling or a big bar of chocolate. Harry was not the greatest at house keeping and neither was Marion who, rumour had it, preferred to keep company with the local brewery workers. So cleaning up his place was a golden opportunity to pry. My Cousin Jackie once claimed to have stumbled upon a supply of pornographic mags, as sold in the shop, while someone else confessed to have eaten several bags of crisps discovered in an open box. Whatever the truth of these tales, it was our chance to poke into Harry’s private life and be guaranteed a reward too.

Harry lived on the two floors above the shop. The place was a mess and he left us with the simple instruction to ‘Get on with it,’ so we did just that. ‘What’s in here?’ was a constant exclamation, with the rejoinder ‘Dunno, better have a look.’ Much of what we found was a mystery to us – invoices, bills and bank statements – exciting things that never seemed to come our way. Whenever we thought he was due to arrive, we rushed about tidying and cleaning to create the impression of working and ensure a good pay out. On one occasion, I got one shilling and sixpence for my efforts but, on another day, only a medium-sized bar of chocolate which drew the verdict of ‘tight bastard’ when I had left the premises. Cousin Jackie once earned half a crown, though I strongly suspect she had actually done some work to earn it, unlike lazy little me.

Harry was generally well-liked in Great Eastern Buildings, allowed credit to the adults and even splitting up packets of cigarettes so people could buy them individually. Rather naughtily, he would also sell single cigarettes to children. Back then, this was simply ‘business’ and smoking was not considered the serious health risk that it is today. Hence, after one or two coughing fits up on the roof of the buildings, I was convinced it was not a good idea. Yet for my cousins Kevin and Leslie, this was the introduction to years of smoking in adulthood.

On most days, you could usually find a packet of five ‘Weights,’ which were the cigarette of choice, on the back shelf at Harry’s, reduced to just two or three fags. If money was tight, then cobbling together one from dog ends was not unknown. God knows the strength of toxins within, thus illustrating the truth of the expression ‘dying for a fag’!

Harry’s goodwill was widely appreciated and he was invited to the weddings of the Harris children when they grew up. I believe he passed away in the mid-eighties, shortly after his shop was compulsorily purchased by the local council for a pitifully low price. By everyone that lived in Great Eastern Buildings, Harry Fishman is warmly remembered to this day.

If Harry was the nice guy of the local retail trade, as far as we were concerned his alter-ego was Leon, a greengrocer who had a small corner shop one hundred yards in the opposite direction down Quaker St. Leon was a short and squat man, no more than 5’ 4” tall and almost equally wide, and we found him simply unpleasant. Unlike Harry, he evinced no humour, no sense of brotherhood or commonality, or even sympathy from the residents of Great Eastern Buildings

When I was reunited with my mother decades later, she recalled how Leon would often try to slip a hand around her waist. He was always trying it on with me until I slapped him, and then I stopped going there,’ she admitted to me. Perhaps wisely, Leon limited the number of kids entering his shop to two at a time. ‘Keep your hands to your sides,’ was his universal greeting barked upon our arrival. I cannot deny our sticky-fingered behaviour yet, equally, he was distinctly threatening to us. He head-butted my school friend Sui Wong, after being informed erroneously that Sui has scratched his car. Perhaps Leon’s hostility was the result of being frequently robbed? I know the Wheler House kids, Willy and Benny Norris, delighted in pilfering his store.

I heard that Sylvie Pattern once got credit or ‘tick’ off Leon but never paid him back, even though he came to her door to collect it. Yet, if Sylvie Pattern had managed to con Leon out of a little credit, he was not averse to such actions himself. Paul Ramsey recalled how his mother sent him to buy groceries and gave him a ten quid note, but Leon only gave him change for a five pounds. Despite Paul’s protests, Leon insisted only a fiver had been passed over yet Paul’s mother had shrewdly made a note of the serial number. When she arrived at Leon’s, there was no ten pound note in the till, although he admitted he had one in his wallet. Once she produced the serial number and matched it with the note in Leon’s wallet, the game was up. Leon grovelled in apology and, by compensation, he gave her a packet of twenty Weights. Leon retired sometime in the late seventies and no one knew what happened to him yet neither – I suspect – did anyone care. Poor Leon, he was never invited to any of our weddings.

Harry Fishman photographed by Clive Murphy, 1987

Harry Fishman’s shop on the corner of Brick Lane and Quaker St photographed by Clive Murphy, 1987

Leon’s shop photographed by Philip Marriage in 1967

Leon’s shop photographed by Alan Dein in the eighties

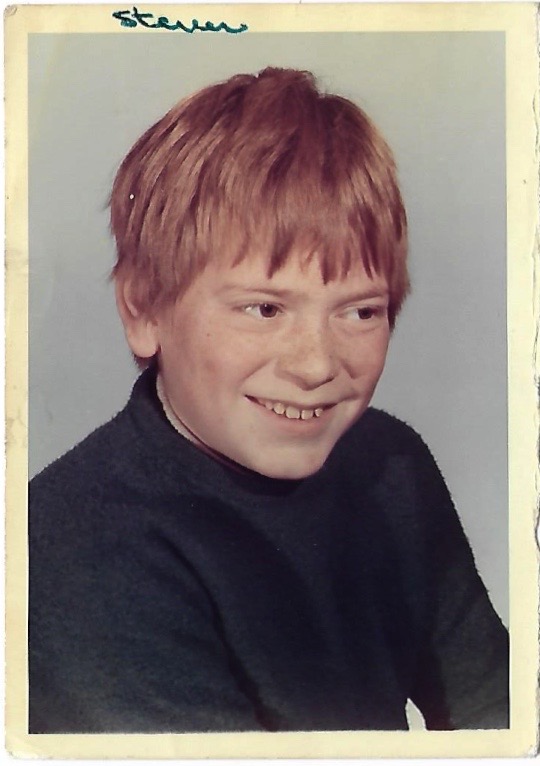

Steven Harris, aged twelve

If you remember Harry Fishman or Leon the Greengrocer, please add your memories in the comments

You may also like to read Steven Harris’ memoir