This is an extract from my article in the current issue of Design Exchange magazine.

One of the most popular posts of recent years has been THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM. Now I have written a book which is a gallery of the most notorious facades and a humorous analysis of facadism - the unfortunate practice of destroying everything apart from the front wall and constructing a new building behind it – revealing why this is happening and what it means.

There are two ways you can help me publish the book.

1. I am seeking readers who are willing to invest £1000 in THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM. In return, we will publish your name in the book and invite you to a celebratory dinner hosted by yours truly. If you would like to know more, please write to me at spitalfieldslife@gmail.com

2. Preorder a copy of THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM and you will receive a signed and inscribed copy in October when the book is published. Click here to preorder your copy

Please suggest other facades I should include.

The Duke of Cambridge was built in 1823

It is rare that you cannot believe your eyes, yet that such was my response when I first saw this chimera. When I examined the proposal for facading of The Duke of Cambridge in Felix St, Bethnal Green, in the planning application for a development by Heath Holdings, designed by Guy Hollaway Associates, I was astonished and appalled at how a new building appeared to have been forceably inserted into an old building to create such a hybrid monster.

At the time, I dismissed it as a dystopian fiction because I could not believe it would ever get built, but the reality is so much worse than the proposal. Such is the ugly conflict between the old and the new, you can almost feel the humiliation and pain of the original building. The experience is akin to your dear old grandpa with the Father Christmas physique having his trousers stolen and you find him wandering bereft in the street, tricked out in a pair of garish lycra shorts as the only option available.

It makes you wonder. How can anyone have thought that this treatment of a gracious nineteenth century pub was sympathetic? Or imagined that the finished result is acceptable as architecture? It stretches my imagination to grasp the aesthetic which permits an architect to arrive at such a disastrous compromise.

On his website, the architect describes it thus – ‘A dynamic glazed box of ‘reglit’ glass tubes juts out of the top of the brown and red brick façade of the original building, creating a relationship between old and new.’ This statement set me thinking about the nature of this relationship.

Guy Hollaway’s new structure crouches like an incubus on top of the old, expressing antipathy for the building it inhabits and denying the potential of any resolution of the diverse elements into a satisfactory architectural whole, which ought surely to be the object of the exercise.

Firstly, the scale, proportion, colour and idiosyncratic placement of the windows in the extension ignore the form of those in The Duke of Cambridge, which now have clunky new frames inserted that differ from the originals, dividing the windows in half laterally and compounding the inelegance.

Secondly, the ‘reglit’ glass tubes with their strong vertical emphasis give the extension the effect of being extruded from the building below. The industrial modernity of these glass tubes is alien in this context, disregarding the brickwork of the pub and mitigating against any integration of the elements into a whole.

Thirdly, the former mansard roof of The Duke of Cambridge was raked, tilting away from the walls beneath and held in place visually by the symmetrical flourishes of the Dutch gable on the front of the building, but the new extension does not resolve the form of the building below. Instead, by avoiding any acknowledgement of the Dutch gable, this crudely disproportionate rectangular box exists in conflict with the rest of the structure to discordant effect.

There is no reason why an architect could not use modern materials in such a project, if the proportion and form of the building unified them within the design. Similarly, I can see that by using traditional materials an architect might extend a building successfully in a form that contrasted with the pre-existing structure. The problem with The Duke of Cambridge is that the choice of form and the materials for the extension are both at odds with what is already there. It is these decisions by the architect not to engage with the old building that deliver a visual eyesore.

I feel disingenuous pointing this out because I would like to think that architects are blessed with a sensitivity for these essential concerns of their trade. I would like to imagine that the architect who chose to put the glass tubes on top of The Duke of Cambridge believed the luminosity of this material might impart a levity to the extension, as if it hovered above its predecessor like a cloud of light, or the beacon of a lighthouse. Yet, even if this were the case, they have failed miserably.

The explanation of why The Duke of Cambridge has been degraded in this way must lie with the two huge new buildings which are part of a larger development by the same architect and developer on the other side of Felix St. Out of a total of more than two hundred dwellings in these buildings, just around 25% are ‘affordable.’

These vast curved blocks possess no relationship in form or scale with the brick terraces of the Hackney Road or the dignified Guinness buildings constructed as social housing a century ago on the opposite side of Felix St. Such is their generic nature, they could equally be placed in Minneapolis or Milton Keynes because stylistically they do not belong anywhere, raising the suspicion that the form is dictated solely by an imperative to maximise volume and financial return rather than entertain any dialogue with the existing urban landscape. It is disappointing to witness how the current housing shortage has delivered a field day for exploitative development across the capital, rather than attempting to address the real needs of Londoners.

Which brings me back to The Duke of Cambridge – because the anachronistic materials and forms which blight this formerly elegant structure, the ‘reglit’ glass tubes and the idiosyncratic window placing, are prominent features of the development across the road. In other words, The Duke of Cambridge has been adulterated in an attempt to unify it with the new housing blocks resulting in a dysfunctional conversation between incompatible languages.

Although The Duke of Cambridge closed in 1998, I am informed there were those who wanted to reopen it and give it new life, which would not have been impossible in this burgeoning neighbourhood. It might have functioned as the place where the residents of the Guinness social housing and the inhabitants of the new development could meet. But the opportunity of providing a public space for fellowship, as the pub had done for the previous one hundred and seventy-five years, was denied by the developer for the sake of cramming in a few more flats, thereby consigning it to the past and retaining the lettering on the facade as a mere historic relic reminding us only of a life that has gone.

We confront the fundamental question of how the financial imperative driving such ill-conceived developments may be reconciled with our need for a city we want to live in, and which serves the needs of all Londoners. The treatment of The Duke of Cambridge incarnates a metaphor of this conflict vividly and the ugliness of the outcome is a pertinent slap in the face, reminding us how blatantly any concern for quality of life or good architecture is being sacrificed for the sake of greed. This disastrous hybrid is an unfortunate totem of where we are now, an object lesson for architectural students of what not to do, and we may be assured future generations will laugh in horror and derision at the folly of it.

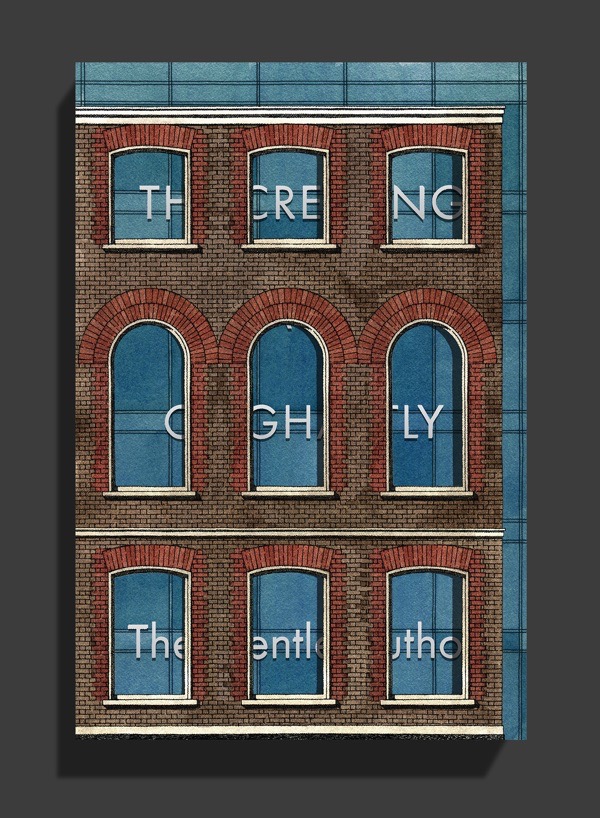

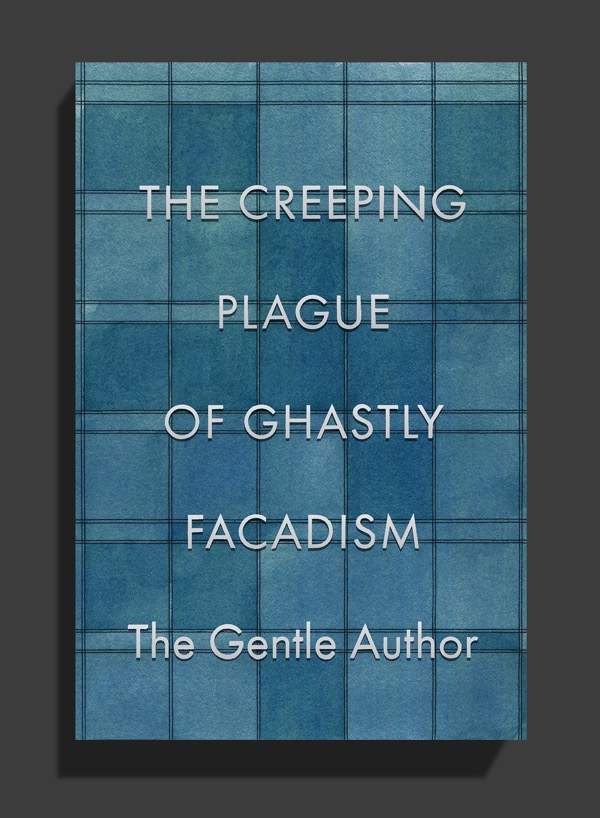

The exterior cover of the book…

…which opens to reveal the title.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A COPY OF THE CREEPING PLAGUE OF GHASTLY FACADISM