The distinguished historian Ruth Richardson makes a last-minute plea for the complex of historic buildings on the site of the listed eighteenth century Cleveland St Workhouse, revealing the participation of Florence Nightingale in the creation of the Nightingale Pavilion Wards added when the Workhouse became a hospital in the nineteenth century.

![fnightingale]()

This Thursday evening, 6th July, the Planning Committee for the Borough of Camden will meet at Camden Town Hall to discuss an application for the redevelopment of the Dickens Workhouse, the Nightingale Pavilion Wards and their attendant buildings in Cleveland St, Fitzrovia, W1.

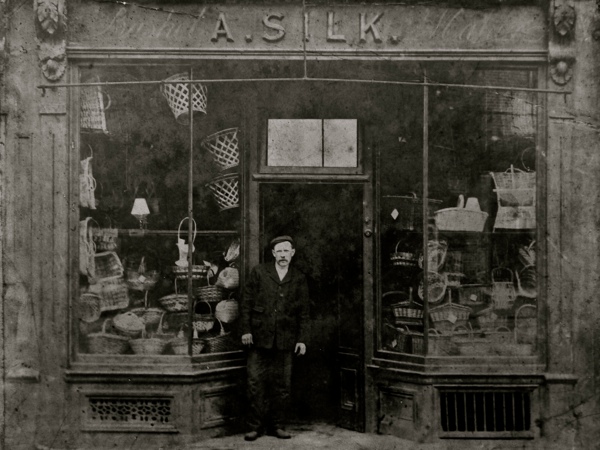

Readers of Spitalfields Life will already be familiar with the discovery that Charles Dickens lived in the same street and the knowledge that, while he was writing Oliver Twist, there was a shop opposite the Workhouse run by a certain Bill Sykes. The story of the poor murdered Italian Boy has also been told in the pages of Spitalfields Life and through him we remember the thousands of Covent Garden parishioners buried in the consecrated burial ground surrounding the Cleveland St Workhouse. Yet the Nightingale Pavilion Wards tell an equally important story of Florence Nightingale’s involvement in the evolution of compassionate medical care in this country towards the National Health Service that we cherish today.

I photographed the site recently and discovered the buildings entirely populated by property guardians, as illustration – if such were needed – of the suitability of all these properties for conversion to residential use rather than the needless and wanton destruction proposed by the developers.

We hope that Camden Council will make a good decision and we want to see the Workhouse, the Nightingale Pavilions, and the other buildings refurbished as housing for local people, because this historic site deserves preservation.

You can see the relevant Planning Applications here:

2017/0415/L - The gutting of the Workhouse at 44 Cleveland St and redevelopment into flats

2017/0414/P - The obliteration of everything else on the site and the erection of an eight-storey tower at 44 Cleveland St

Comments are still being accepted by the Planning Officer (who is recommending the developer’s plans to the Planning Committee for approval). PLEASE CLICK HERE TO MAKE YOUR COMMENT. Quote the numbers of the Planning Applications and be sure to make it clear if you are objecting.

ALTERNATIVELY, you can write direct to Kate.Henry@camden.gov.uk – be sure to quote the numbers of the Planning Applications and your postal address and make it clear if you are objecting

Click here to read the Council for British Archaeology’s letter of objection

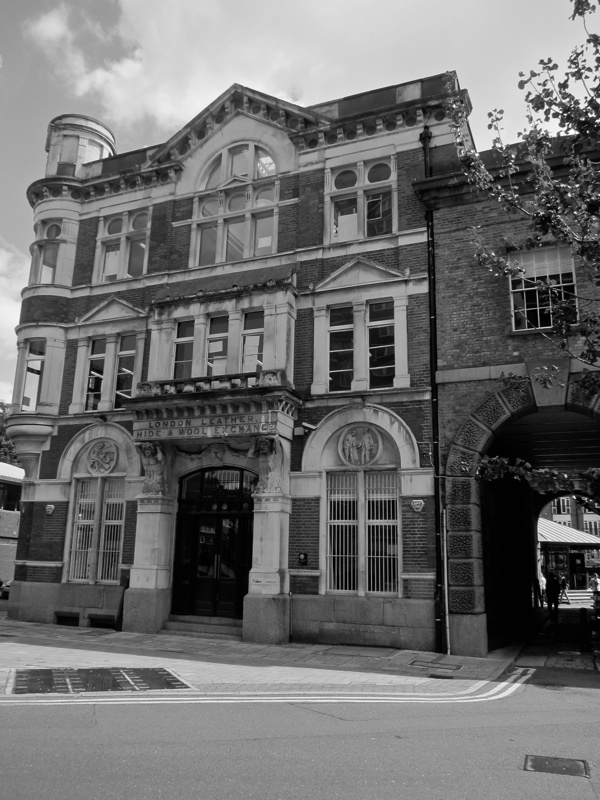

![L1000247]()

The Workhouse

The Workhouse was built in the seventeen-seventies as an ‘H’ shaped block fronting onto Cleveland St with wings at front and rear. Originally the poorhouse for the parish of Covent Garden, it became the Strand Union Workhouse in the eighteen-thirties, serving a union of parishes in the Strand district under the hated New Poor Law. Charles Dickens was aware of the changing regime and wrote about it in Oliver Twist. As a closed institution, the wider public had only fearful knowledge of what went on inside. For the next forty years, Cleveland St Workhouse was among the worst of London workhouses, ameliorated only in the eighteen-fifties by the kindly ministrations of Dr Joseph Rogers, and the flowers and prayers of Miss Louisa Twining, founder of the Workhouse Visiting movement.

When the Strand Union Workhouse was investigated by The Lancet Sanitary Commission in the eighteen-sixties, they found more than five hundred people were sharing around three hundred beds, crammed together so tightly that access was often only from the foot of each bed. There was one medic, and no paid or trained nurses and over 90% of the inmates were sick, dying, disabled, infirm, elderly, mentally handicapped, nursing mothers or children. Fewer than 10% of the inhabitants were ‘able-bodied’ and it was they who nursed everybody else. The food was poor, cleanliness objectionable, latrines insanitary, and so on.

The Plans

The current developer’s plans for the Workhouse site – which they call the “Middlesex Hospital Annex ” – make little improvement on their last attempt, an abominable design with two new blocks covered in a bright green cladding flanking the eighteenth century workhouse. Only a few concessions have been granted: the frontages of the Victorian Masters’ and Matrons’ houses, which have stood either side of the main Workhouse frontage for around one hundred and fifty years, are to remain. Also a portion of the elegant front wall built in the early twentieth century will survive, though unfortunately in an asymmetric form. Anyone looking at these new plans would be forgiven for thinking it is the same scheme in a new guise.

These plans reduce the Workhouse building to a shell, destroying its interior, its roof, its back wall, every window and everything attached to it. The plan proposes the entire destruction of the rest of the site, including the two fine Nightingale Pavilions attached to the rear of the Workhouse, all the hospital staff accommodation, the mortuary and its chapel. All this for a generic eight storey block.

The Singing Soil

The developers deflect any criticism of their current plans from historians by employing an ex-employee of English Heritage to write a report emphasising the lack of destructive potential in their projected ‘development.’ So it is no surprise to read that, apparently, nothing on the site is worth saving. By suggesting that burials were confined to a small area on the north side, the report also argues that few remain. Yet we know burials were made all over the site. Human remains have been encountered whenever building work has been undertaken and, in the nineteenth century, Dr Rogers described deep graves going down more than twenty feet.

The precise dimensions of the Workhouse site are known from a vellum map dated 1790. It records the area dedicated to the eternal rest of the dead at an outdoor service of consecration led by the Anglican Bishop of London, Beilby Porteous, who promised the parishioners of Covent Garden buried there they would be free from all indignity “for ever.” Unfortunately, this sacred map and the promise it contains have been treated by the developer’s heritage consultant as if it were of no more significance than an estate agent’s record of property ownership.

Since the publication of my piece on the Italian Boy in these pages, the ominous silence concerning the presence of the dead has been addressed by an archaeological report which appeared on the Camden Planning website. Rather than entertain the likelihood that this graveyard offers a rare opportunity for archaeologists to excavate an eighteenth century extra-mural parish burial ground for the poor, this report suggests that if the remains buried there are found to be disarticulated (ie jumbled) then it is suggested that a ‘watching brief’ would be a sufficient role for archaeologists. Consequently, despite Bishop Beilby’s promise, merely an archaeological ‘oversight’ of the excavation of the dead is intended and the de-sacralizing of this consecrated site by means of a contractor’s JCB is contemplated with disquieting equanimity.

Some might suggest this treatment is entirely consistent with a burial ground run for decades by Mr Bumble and his kind, that was situated conveniently opposite a medical school connected to the Workhouse by a tunnel under the road. The glazed pavers which remain to this day in the pavement outside the Master’s house reveal the route. The 1832 Anatomy Act, directing that any pauper might be dissected before burial, is apparently of no material consideration in this case. Those archaeological experts employed by the developer appear blissfully unaware of the sardonic moment in Oliver Twist when the parish undertaker offers Mr Bumble a pinch of snuff from his own patent-coffin-shaped snuffbox.

The Nightingale Pavilions

Most curiously, no-one within the developer’s extensive payroll seems to have made any serious effort to examine the history of the Nightingale Pavilions which replaced the rear wings of the Workhouse, preserving the building’s original footprint on a larger scale. Yet they carry an important history, even if in the current plans they are to be obliterated.

The pair of Nightingale Pavilions are good quality buildings which have plenty of life in them yet. Each contains three floors of Nightingale wards, their solid walls punctuated by tall windows and sanitation towers placed midway along their external flanks. Between these Pavilions lies an unexpectedly large open space which was the principal part of the graveyard, probably still largely undisturbed and currently occupied by portacabins and glazed structures with shallow foundations. The Pavilions are robustly built of good brick, with contrasting darker red-brick string-courses and neatly matching window arches in the characteristic Victorian manner.

Although the developer’s heritage consultant insists that the Pavilion wards must not be referred to as “Nightingale” wards and denies strenuously that Florence Nightingale had anything to do with them, he is mistaken. This fine pair of structures are most certainly Nightingale Pavilions containing Nightingale Wards and they deserve to be accurately recognised as unique examples of such before Camden Council’s Planning Committee contemplates their obliteration.

These buildings can legitimately be called “Nightingale Pavilion Wards” because they were built to accord with Florence Nightingale’s specifications by an architect known to her and she made her own personal proposals for their use.

Florence Nightingale & the Transformation of Cleveland St

To understand Florence Nightingale’s involvement with Cleveland St, we have to look back to the eighteen-fifties, which saw the Great Exhibition, a cholera epidemic, and war in the Crimea. The first of these provided a national self-image of social cohesion and peaceful co-existence after the unsuccessful push for greater democracy by the Chartists and the disruptive impact of the revolutions across Europe in 1848. The Crimean War was a watershed in the home territory – the sheer incompetence of the army to provide for its own sick and wounded exposed repugnant attitudes towards ordinary soldiery. Lord William Paulet told Florence Nightingale that she was ‘pampering the brutes’ and she never forgot it.

Florence Nightingale was a deeply religious woman who pondered long and hard upon the nature of Charity and why God had caused Jesus Christ to be born into the working classes. For her, every life was sacred and, although she had been groomed for a high society marriage, she chose a different destiny for herself. Successfully battling her family’s opposition to becoming a nurse, she became superintendent of a hospital for ladies in Harley St. During the notorious John Snow cholera epidemic of August and September 1854, the huge influx of desperately ill and dying poor to the hospitals became the catalyst for her to leave the Harley St ladies’ institution in the hands of her well-trained subordinates in order to nurse those in far greater need – cholera patients at the Middlesex Hospital.

She found this experience of nursing in the Middlesex Hospital invaluable in her later work on hospital design. Not long afterwards, Florence Nightingale was called to serve in the Crimea and she returned from this searing experience with a determination not to forget the thousands of servicemen who had needlessly died there, not of wounds but of infections and epidemic diseases. She was intolerant of official obfuscation after witnessing the sanitary improvements at Scutari which had saved so many lives and she fought for the rest of her life for improvements in hospital provision and nursing care. Her designs for and advocacy of Pavilion plan hospitals emerged directly from her personal nursing experience.

After her return from the War, she wrote three important editorials in the most influential architectural journal of the day, The Builder. Initially a critique of a poorly designed new military hospital at Netley, Florence Nightingale laid out the arguments for improved hospital design. These anonymously published editorials were reprinted in her Notes on Hospitals, which famously opens with the words: ‘The first requirement in a hospital is that it should do the sick no harm’. This book consolidated her ideas about hospitals organised to promote health, rather than merely to contain the sick. She realised many hospitals fostered illness and death among patients and staff. Alongside good diet and professional nursing, her fundamental lessons for hospital design were ventilation, cleanliness, light, air and space for every patient, including ventilated plumbing facilities in every ward. Tall windows were key to her vision, as they provided both good light and high-level ventilation, and served to space beds apart, providing access for nursing care, and helping to prevent the spread of disease. These ideas were enormously influential. Architects scrambled to have their work endorsed by her and charitable hospitals were swift to adopt her Pavilions in their plans.

Next, Florence Nightingale turned her sights on the moribund Poor Law workhouse system. To her, a patient was anyone requiring nursing care and she argued that if the sick and children were taken out of the workhouses, the Poor Law could operate better for those for whom it was intended – the healthy poor, which was less than 10% of the total workhouse population.

Her ideas and practical recommendations for hospitals assisted the efforts of workhouse reformers, such as those of the Cleveland St doctor Dr Joseph Rogers, the Lancet Sanitary Commission, and the nationwide workhouse-visiting pioneer Louisa Twining, whose work began at Cleveland St. Eventually, administration of the Poor Law was transferred to a new body, the Local Government Board and, once the separation of the sick from the healthy became official policy, a new building programme began. The poor from Cleveland St were transferred to a new building at Edmonton and the Workhouse itself upgraded with the addition of two new Nightingale Pavilions.

The architect of these Nightingale Pavilion Wards was John Giles, who corresponded with Florence Nightingale concerning his designs for the new Poor Law Infirmary at Highgate, which he built according to her principles. He had read her Notes on Hospitals and letters survive which confirm that he invited her to look over his drawings and suggest improvements.

Yet Florence Nightingale had plans of her own for the upgraded Cleveland St Workhouse. Using the Nightingale Fund, collected for her own use after the Crimean War, she had established a training school for nurses at the new St Thomas’s Hospital and planned to do the same for workhouse nursing at Cleveland St. She and Sir Sidney Waterlow conferred over the appointment of a Nightingale-trained nurse as Matron of the new Asylum, which would have enabled the establishment of a Nightingale training school at Cleveland St. Unfortunately, the parish Guardians swiftly appointed a non-Nightingale nurse to avoid any challenge to their governance.

Thus Florence Nightingale’s association with Cleveland St and its Nightingale Pavilion Wards is five-fold:

1. Her Builder editorials, consolidated in Notes on Hospitals, laid out the fundamental design criteria for Pavilion wings and wards, to which those in Cleveland St conform.

2. Florence Nightingale was a key figure in the post-Crimean War Poor Law amelioration movement, which emerged from Cleveland St Workhouse, led by its Medical Officer Dr Joseph Rogers and by Miss Louisa Twining.

3. Florence Nightingale’s argument that class should not be a consideration in the care of the sick brought about the separation of the infirm and dying from the healthy in workhouses, which led directly to the creation of the Central London Sick Asylum in Cleveland St.

4. The architect of the new Pavilion wings, John Giles, knew Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Hospitals and conferred directly with her concerning the design of Pavilion Wards.

5. Florence Nightingale had well-developed plans for a nursing school in the new infirmary at Cleveland St, but was stymied by what she called “Poor Law Mindedness.”

The Nightingale Pavilions are perhaps unique in England in being attached to an eighteenth century poorhouse. Historic England know of no other instance while Jeremy Taylor, leading historian of Pavilion Plan hospitals, thinks the Cleveland St assemblage is highly unusual and Peter Higginbotham, the author of the workhouses.org believes its configuration is unique.

The Euston Arch and St Pancras Station are precedents in this case – two Camden buildings, the one controversially destroyed and the other preserved for magnificent new use. These Nightingale Pavilion Wards are an important monument to Florence Nightingale and to what she called her ‘children’ – the thousands of working-class soldiers who died needlessly in the Crimea. These buildings deserve to be preserved as witness to this history and re-used to provide much-needed good quality housing for Londoners.

![L1000164]()

Nightingale Pavilion Ward

![L1000175]()

Rear view of the Workhouse with Nightingale Pavilion wings on either side

![L1000010]()

Windows on the south wing of the Workhouse

![L1000212]()

Window on the front of the Workhouse

![L1000016]()

Stone bollard on the side of the Workhouse

![L1000032]()

Sanitation tower attached to the south Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000039]()

The Matrons’ House

![L1000063]()

Eastern extent of the south Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000069]()

Bow windows where the Nightingale Pavilions meet the Workhouse building

![L1000142]()

Architectural integration of the Workhouse and the north Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000076]()

Looking from the Workhouse towards the north Nightingale Pavilion ward

![L1000123]()

Elevation of the north Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000117]()

The south Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000146]()

End wall of south Nightingale Pavilion

![L1000139]()

Looking back towards the Workhouse across the burial ground occupied by one storey modern buildings

![L1000074]()

View east from the Workhouse

![L1000151]()

Gallery linking the Nightingale Pavilions

![L1000188]()

Staircase at rear of the Workhouse

![L1000114]()

Eighteenth century staircase in the Workhouse

![L1000231]()

Cantilevered stone steps

![L1000202]()

Looking up the stairwell

![L1000205]()

Decorative cast iron newel post

![L1000093]()

Chimney pot details

![L1000098]()

Sanitary tower attached to the Workhouse

![L1000198]()

Elevation of the Masters’ House

![L1000195]()

Detail of the Masters’ House

![L1000130]()

The Masters’ House

![L1000210]()

Entrance to the Masters’ House

![L1000242]()

The Masters’ House seen from Cleveland St with the glass pavers just visible in the pavement beneath the end wall, indicating the tunnel used for carting the corpses of paupers under the road to the medical school opposite for dissection

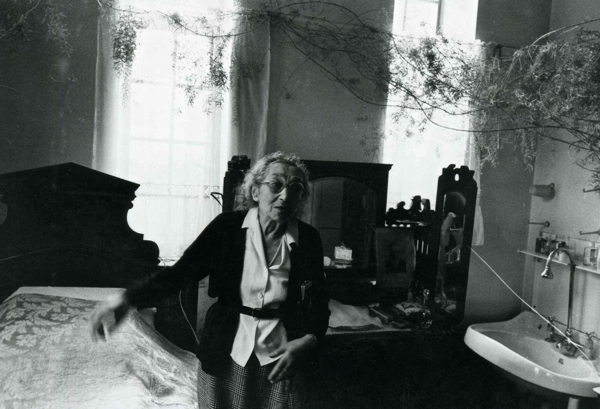

![L1000189]()

The presiding spirit of Cleveland St

You may also like to read

At The Cleveland St Workhouse

At Charles Dickens’ Childhood Home

The Italian Boy

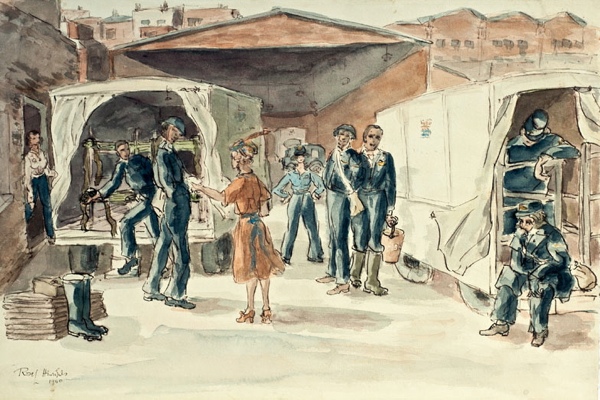

![Dual Purpose, Fairclough Street [School Yard], Tilbury Behind,1940](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Dual-Purpose-Fairclough-Street-School-Yard-Tilbury-Behind1940.jpg)

![Club Row [Animal Market] Carries On, 1943](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Club-Row-Animal-Market-Carries-On-1943.jpg)