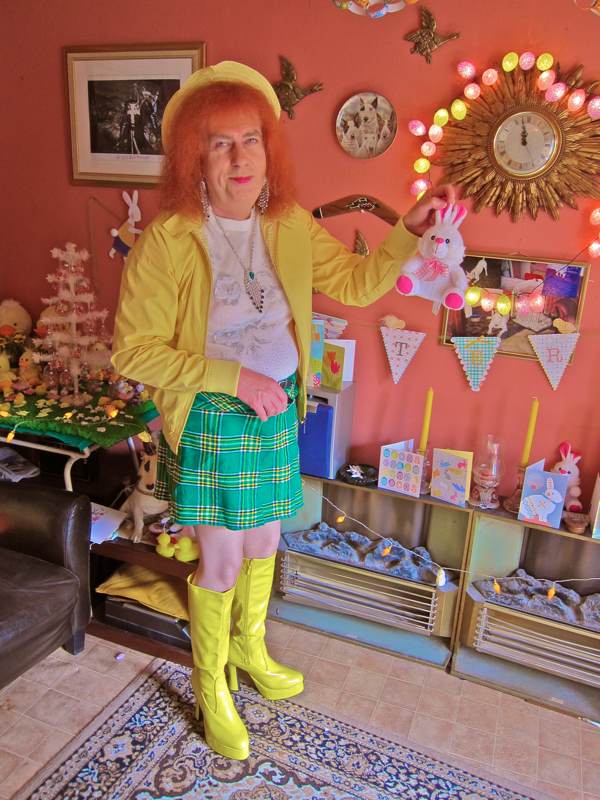

Dan Cruickshank speaks to SAVE NORTON FOLGATE at Shoreditch Church at 6:30pm on Wednesday 22nd April, with guests Sian Phillips reading the poetry of Sir John Betjeman and Conservation Consultant Alec Forshaw dissecting the British Land scheme. Dan will be telling the story of how British Land were defeated in Norton Folgate in 1977 and today he gives us a taster, reminiscing about battles old and new in Spitalfields. Click here to book your free ticket.

![L2082319]()

Seven years ago, I became involved in a strange East End adventure. At that time there was a plan to level the buildings on the west side of Norton Folgate, destroying a robust piece of railway architecture from around 1890 which, at the time, was used as a bar called The Light. All was to be replaced by a large-scale development named Principal Place, designed by Foster and Partners and incorporating a fifty-storey residential tower.

I have lived in Spitalfields since 1978 – my house is only a few minutes walk east from the site – and, like many, I could not see why a fine building in productive and convivial use, making many people happy, should be swept away so that a few people could make a great deal of money. A campaign to save the building was launched but the going was tough since the developers insisted that all had to be cleared, so their ‘vision’ for the new Norton Folgate could be realised, and local authorities showed little interest in the existing buildings or the extraordinary history of this small yet ancient part of London, that has a somewhat mysterious and exotic past.

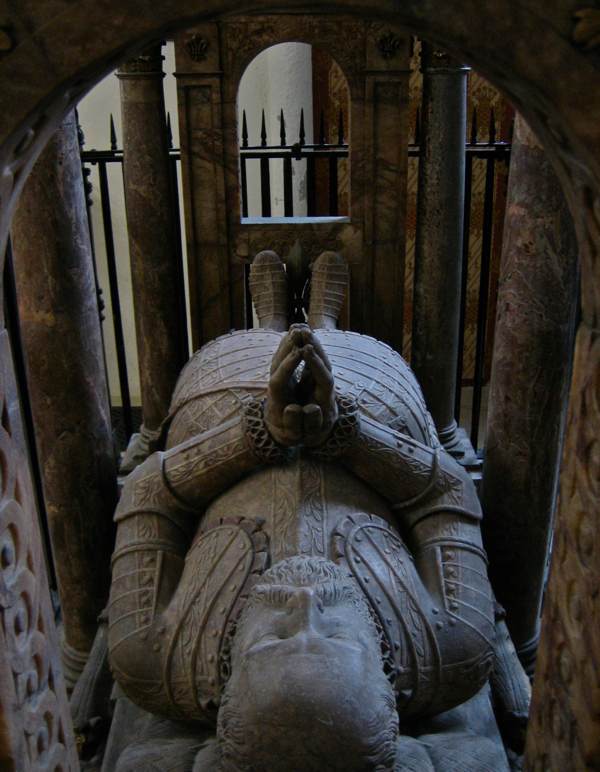

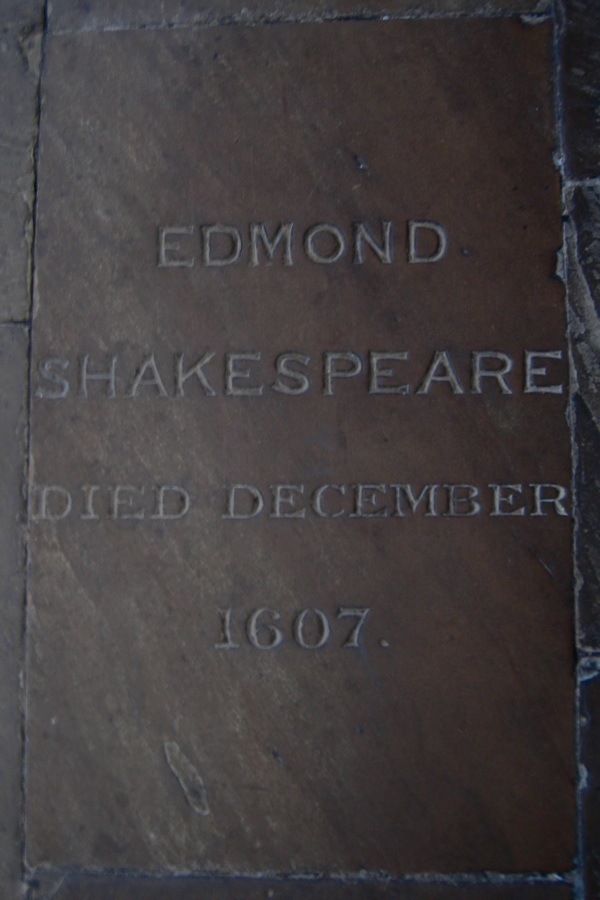

The Liberty of Norton Folgate sits astride the Roman Ermine St in an area that contains part of the northern cemetery of Roman London, an early twelfth century emergency cemetery (perhaps related to a disastrous famine) and, from 1197, the main portion of the Augustinian Priory of St. Mary. The Liberty’s association with death continued after the foundation of the Priory, so that by the time it was ‘dissolved’ in the 1530s around 10,000 bodies had been deposited in its grounds, mostly in the Liberty of Norton Folgate.

Given the radical nature of the Reformation, the winding-up of the Priory seems to have been inevitable but, in fact, it almost survived. The Lord Mayor and Corporation of London lobbied Thomas Cromwell for its preservation for the reception of the ill and those needing medical assistance, notably woman in labour. Elsewhere, the Lord Mayor and Corporation were successful in their campaigns to save the former monastic establishments that became St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, St. Thomas’s Hospital and Bedlam. The fact that these medieval institutions survived the Reformations to continue their useful functions is one of the more pleasing tales of sixteenth century London.

But, sadly, Lord Mayor and City Corporation failed to save what would have become St. Mary’s Hospital in what, by the mid-sixteenth century, had become known as Spitalfields, named after the hospital – or ‘spital – in the fields. So St. Mary’s is London great ‘lost’ London hospital, with the vacuum not filled until 1740 when the London Hospital, serving the City and the East End, and funded through subscription, was founded in Moorfields before moving to Goodman’s Fields and then in 1757 to Whitechapel.

In the 1530s, the land of the Liberty of Norton Folgate passed to secular control with its government eventually vested in the hands its ‘antient’ inhabitants. This secular Liberty inherited some of the key characteristics of its monastic predecessor. The Augustinians, with their fine and large church, were outside the system of parishes, three of which lapped around its borders – St. Botolph to the south and west, St. Leonard to the north, and St. Dunstan to the east. Parishes were not only centres of religious life but also units of local government and – potentially – of political and social control. In addition, the Liberty of Norton Folgate was also largely outside the control of the City of London because the boundary of the City’s ward of Bishopsgate Without met, but did not overlap, the Liberty’s border. Governed by officers chosen annually from among its eligible residents and maintained through taxes raised within its boundaries, the Liberty survived until parish-based local government passed into the hands of the newly created London County Council in 1900.

At the time of the threat to The Light, I was horrified by the ignorance and brutalism of the building industry and the authorities but, while I was left feeling painfully impotent as disaster loomed, a fellow campaigner came up with a brilliantly creative idea.

Research suggested that there was a legal anomaly in the legislation that transferred power from London’s parishes to the LCC. The Liberty of Norton Folgate was not mentioned in documentation so – it was argued – since the Liberty had not been legally divested of its powers, it still existed as a sovereign London authority. This meant that its territory was not subject to the control of the London Boroughs of Hackney or Tower Hamlets and therefore permissions granted by them were not lawful or valid. Instead, governance was legally the right of its elected ‘antient’ residents. It was heady stuff – ‘Passport to Pimlico’ come to life – and instantly the local residents held an ad-hoc election to nominate officers of the Liberty.

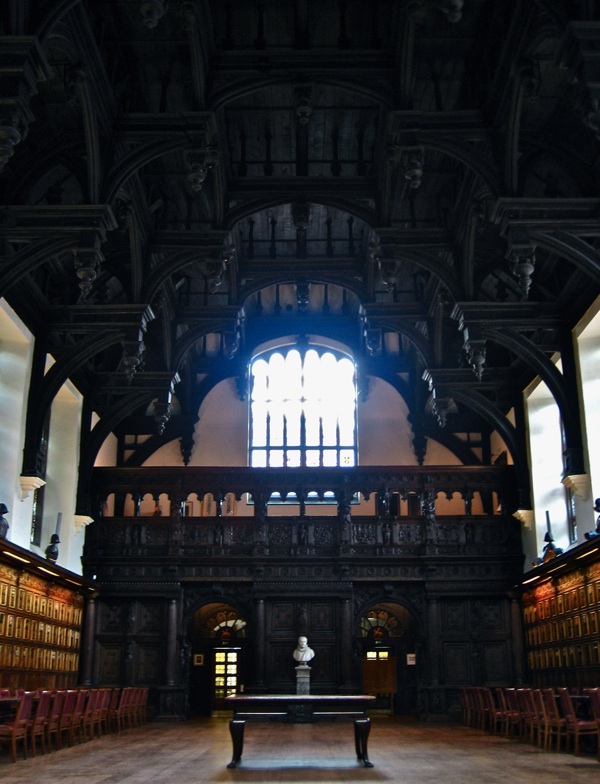

The structure of the Liberty’s government, medieval and manorial, is well described in a draft Act of Parliament for running the Liberty that dates from 1759 and is preserved in Tower Hamlets’ Local History Library. It records that, by tradition, the officers chosen from among the Liberty’s ‘antient’ inhabitants were Headborough, Constable, Overseer and Scavenger who – collectively – were responsible for lighting, cleansing, policing and courts of the Liberty, and for the collection of the local taxes. The Headborough was the senior officer akin to Mayor. These jobs were not token but practical, and could be time-demanding and onerous. Eligible inhabitants might decline the honour of serving the Liberty when their turn came, but had to pay a fine of £10 – a large sum in the mid-eighteenth century when the average wage for a London journeymen was around £50 a year.

The draft Act of Parliament of 1759 offers fascinating detail about life in what was a well-ordered and prosperous part of London at that time. The locally-raised taxes – which, like the national Land Tax, were charged to occupants and based on the rental value of the houses they occupied – were used to pay for a Beadle, six Night-Watchmen, the daily collection of rubbish and a handsome array of globular street lamps, fixed to houses and on stanchions. The 1759 Liberty minute books reveal the mechanism by which the residents acted to assure the smooth governance of their Liberty. The minute book for June that year records that twenty-eight residents were present at a meeting and resolved to employ the beadle at £20 per annum. The Beadle was to ‘set the watch, attend at the watch house, attend collectors in collecting ye rates…keep the Liberty free of vagabonds and people making a shop to sell fruit etc…keep the book which of the watchmen’s turn it is to be on each stand [and] to be a constant resident of the Liberty.’ It was also resolved that six Watchmen (or Charleys) were to be hired at £12 per annum each. These Watchmen were to ‘Beat the round every half hour, watch from 9 o’clock in the evening to six in ye morning from Michaelmas to Ladyday, and from 10 in the evening to four in the morning from Ladyday to Michaelmas.’

A subsequent meeting of occupants of the Liberty determined how its paid work-force was to conduct itself. They were to ‘apprehend and detain Malefactors, Rogues, Vagabonds, Disturbers of the Peace and all Persons whom they have just reason to suspect have any evil designs…deliver to the Constable or Headborough…or the Beadle’ and then ‘with all convenient speed…to…some justice or justices of the Peace to be examined and dealt with according to law.’ The Watchmen were especially instructed to ‘apprehend any Person casting the night soil in the street and carry them to the watch house.’ This instruction suggests this was a particularly common offence.

The effectiveness of the Liberty’s body of Watchmen is open to question. The average age of the six appointed in 1759 was fifty-two, two were described as having bad eyesight and, by October 1759, one of the Watchmen had been dismissed after an earlier reprimand for missing thirty-three nights in one quarter. But, decrepit as the Night Watchmen may have been, it seems clear that in the mid-eighteenth century the Liberty was a model piece of city – well lit, cleaned and watched – which is not surprising since, at that moment of history, it was a wealthy neighbourhood. Spital Sq – developed from the late seventeenth century in ad-hoc manner out of Spital Yard, a former monastic space – was home to some of the leading occupants of the Liberty, with terrace of merchant palaces built along its eastern arm in the early 1730s.

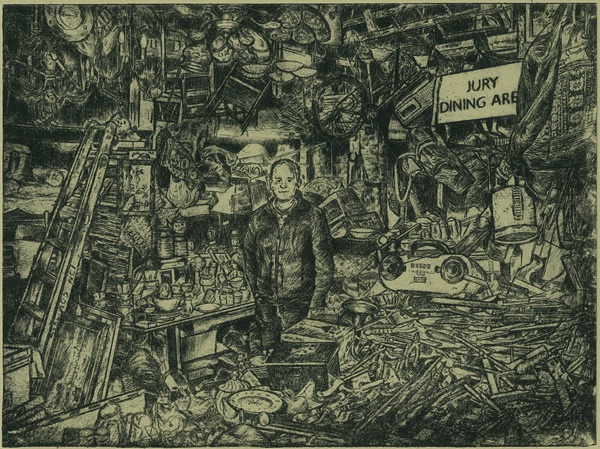

Thus it was that, seven years ago, I became Headborough for a day with various of my neighbours filling other posts and we were joined by distinguished visitors, including Suggs of Madness. Our re-launch of the Liberty was not entirely fruitless. Ultimately, it succeeded in saving a large portion of the railway building occupied by The Light but, while the body of it was saved, the fate of its soul remains in doubt. The Light has gone today, the place stands boarded up and shorn of its western wing, awaiting its fate. Its future is currently scheduled as a place of fine dining in the shadow of the fifty storey tower that will eventually loom over it. Yet this tower is now the least of the problems challenging the survival of the Liberty.

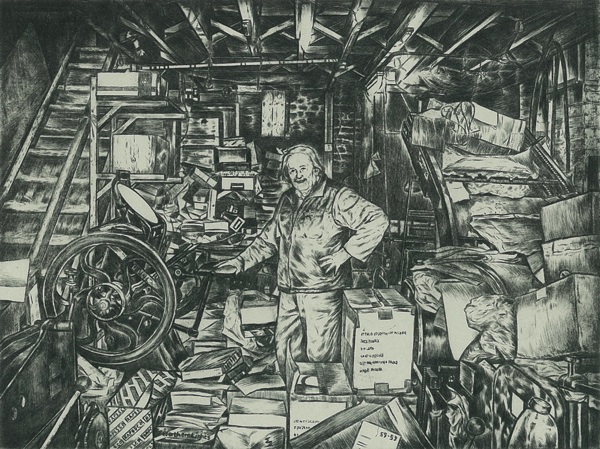

On the east side of Norton Folgate, the former Nicholls & Clarke buildings stand in the way of a dread and brutish British Land proposed development. British Land’s proposal would, if given planning permission, create a terrifying precedent undermining all historic quarters throughout the country.

The particular site in British Land’s target has in recent years been acquired by the City of London Corporation as British Land’s collaborator in this scheme and it lies entirely within, and forms a large portion of, the Elder St Conservation Area. By law, developments in Conservation Areas must protect, reflect and enhance the existing architectural and social character, and preserve existing historic fabric. Tower Hamlets Council in its 2007 Appraisal of the Elder St Conservation Area puts the case correctly, ‘Overall this is a cohesive area that has little capacity for change. Future needs should be met by the sensitive repair of the historic building stock …….. Historic structures and buildings should be retained, and new development should respect the urban form, scale and block structure.’

The existing buildings include a fine row of warehouses of 1886, some of which contain their original, iron-framed interiors. These would be demolished, with only portions of their facades retained, if the British Land scheme gets planning permission. Indeed British Land proposes to demolish over seventy per cent of the existing buildings within the portion of the Conservation Area it controls, mostly replacing them with large-floor plate commercial buildings that rise as high as thirteen stories, instead of the general four-story height of existing buildings. If this happens, the Liberty – whose architectural and social character is still discernible in its street pattern and the tight grain of its buildings and mix of uses – would become no more that a bland corporate enclave of the City of London.

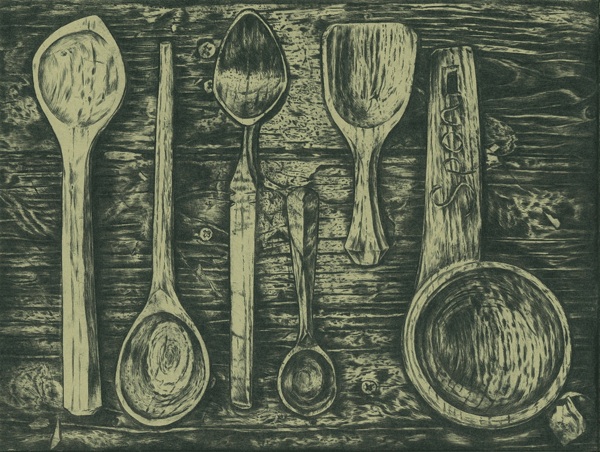

For me, this ghastly scheme possesses a particularly ghoulish character as an awful reminder of the cyclical – and seemingly futile – nature of human affairs. There is a sinister sense of déja vu. Before I moved into my house, I had battled for the existence of the early eighteenth century houses on Elder St’s east side. I was a trustee of the Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust which had just been formed and, in the late summer of 1977, we fought to save the two most ruinous and threated houses in Elder St – 5 and 7 – which in their plan and details were particularly interesting. We thought if we could save these houses – or even if we failed but made a huge and public fuss – the rest of the street might be saved. We occupied 5 and 7, and we challenged the Development Company (which owned them and desired their demolition and the conversion of neighbouring houses into offices), the Housing Association (that hoped to acquire the site of 5 and 7 for flats), the Historic Buildings Department of the Greater London Council – and, of course, Tower Hamlets Council.

The contest dragged on for weeks – seemingly for months – and we had been lulled into a sense of false security when the developers regained possession of 5 and 7, and demolition men were immediately moved in. The roof of number 7 was ripped off within hours, but then it was demonstrated that the developers, by failing to give the GLC twenty-four hours notice of demolition, were in breach of their consents. So the demolition men were ejected and we regained possession, and patched up the shattered roof structure with tarpaulins. It was a stalemate. Tougher anti-squatting legislation was on its way – time was against us. The developers would not talk with us, so we moved things forward by occupying their offices in Portman Sq and seeking publicity. A high point was when we were visited and offered public support by Sir John Betjeman in Elder St. The sight of Betjeman – paper cup in hand (with I seem to remember white wine) – tottering along the street, ducking under raking shores, was memorable. The newspapers loved it.

Finally, against all expectation, the Leader of Tower Hamlets Council spoke up and gave the Spitalfields Trust his blessing, saying that we were acting to save the history of Tower Hamlets for the people of the area. This timely political support made all the difference and the Trust was able to buy 5 and 7 Elder Street, repair them and sell them on. This was a watershed in the recent history of Spitalfields. Then the developers put the rest of the houses on the east side of Elder Street on the market and they were bought by people willing and able to repair them and live in them, and this set in motion the revival of houses in the main Georgian streets of Spitalfields. It seemed – at last – Spitalfields was saved.

But now the shadow of demolition and over-scaled commercial development has returned to threaten buildings within a few metres of the site of the Trust’s epoch-making victory nearly forty years ago. And to highlight the frightful symmetry of events then and now – the predatory development company we fought off back in the seventies has returned and is the current opponent – British Land.

As the Trust fought then, we will fight now – with a firm belief in the justice of our cause. We want to save Spitalfields – with its rich mix of historic and old buildings, distinct character and special atmosphere – for the people of London and for visitors expecting to find something beyond familiar, bland corporate plazas. As we did forty years ago, we want to save Spitalfields from those who seek merely to exploit it as a means to make themselves rich at the expense of the happiness of others.

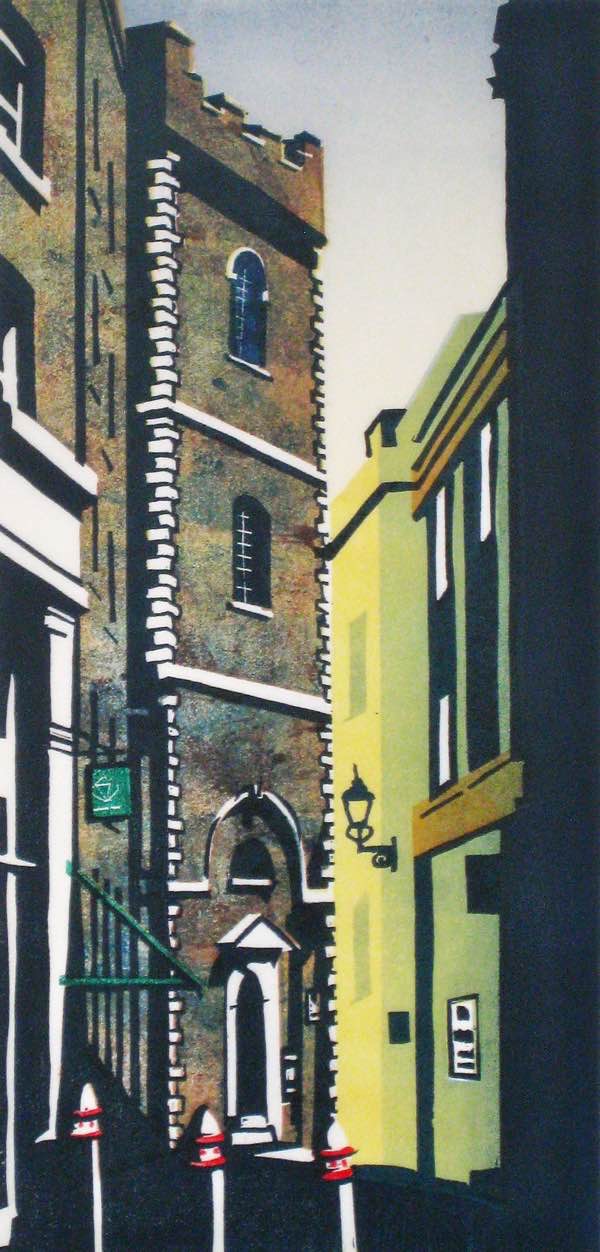

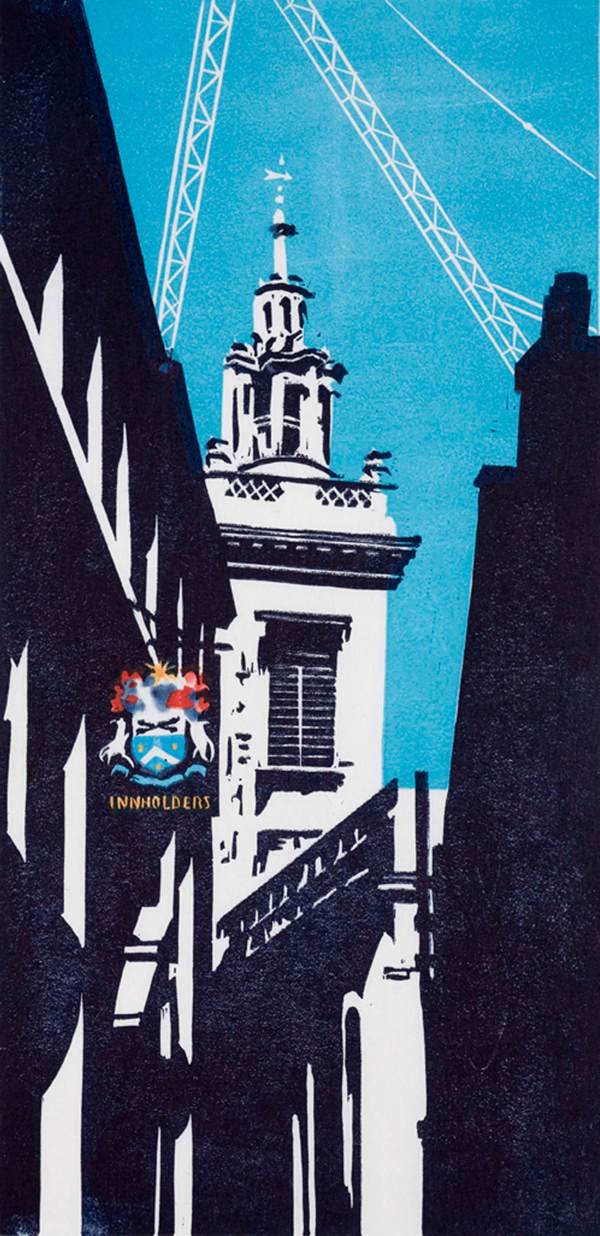

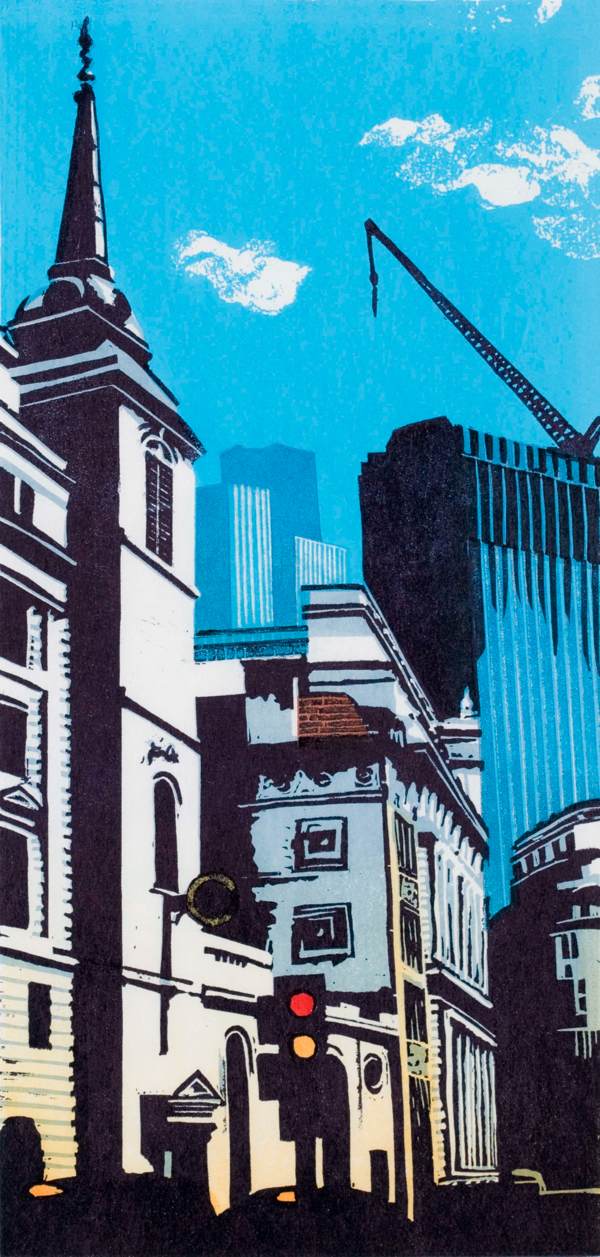

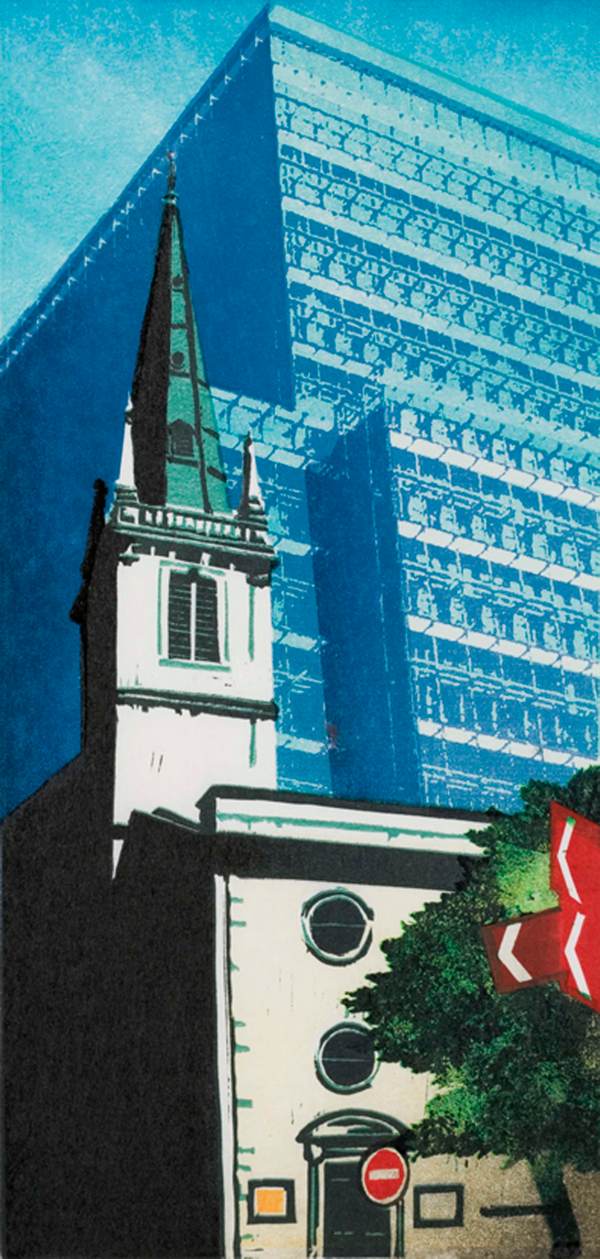

![L2082409]()

Blossom St

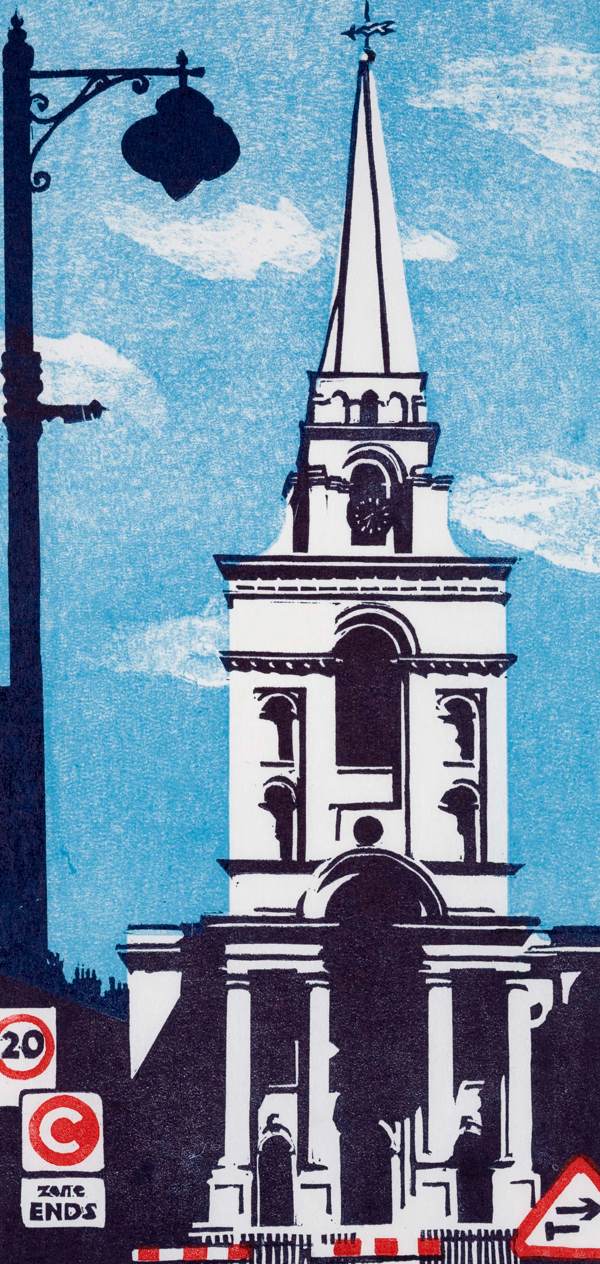

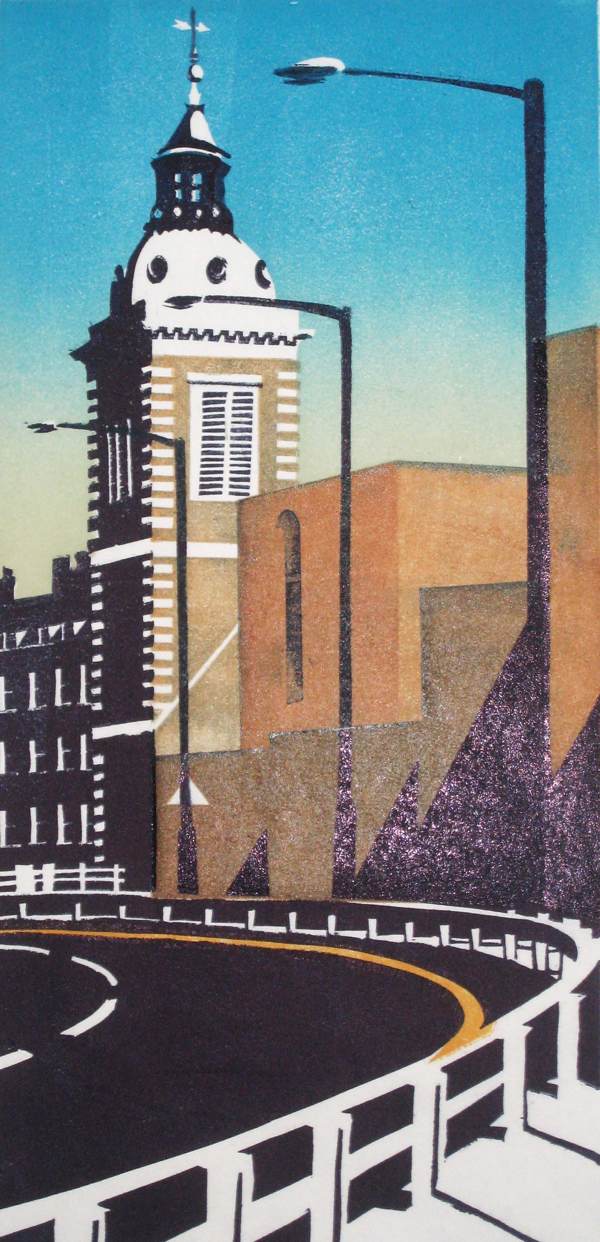

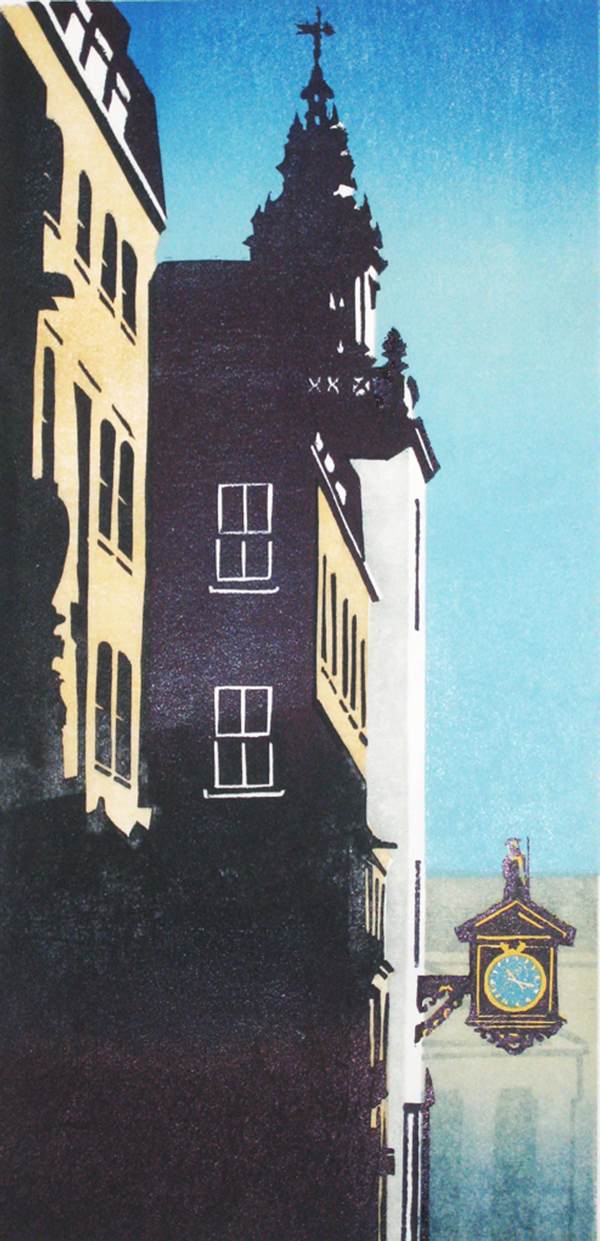

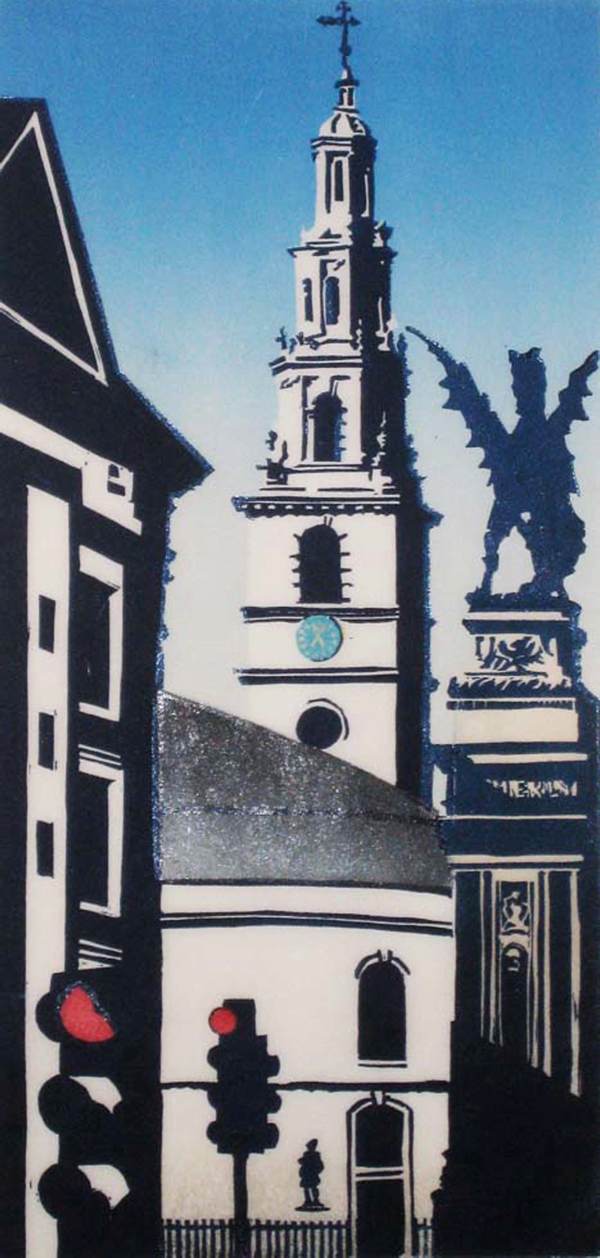

![L2082346]()

Fleur de Lys Passage

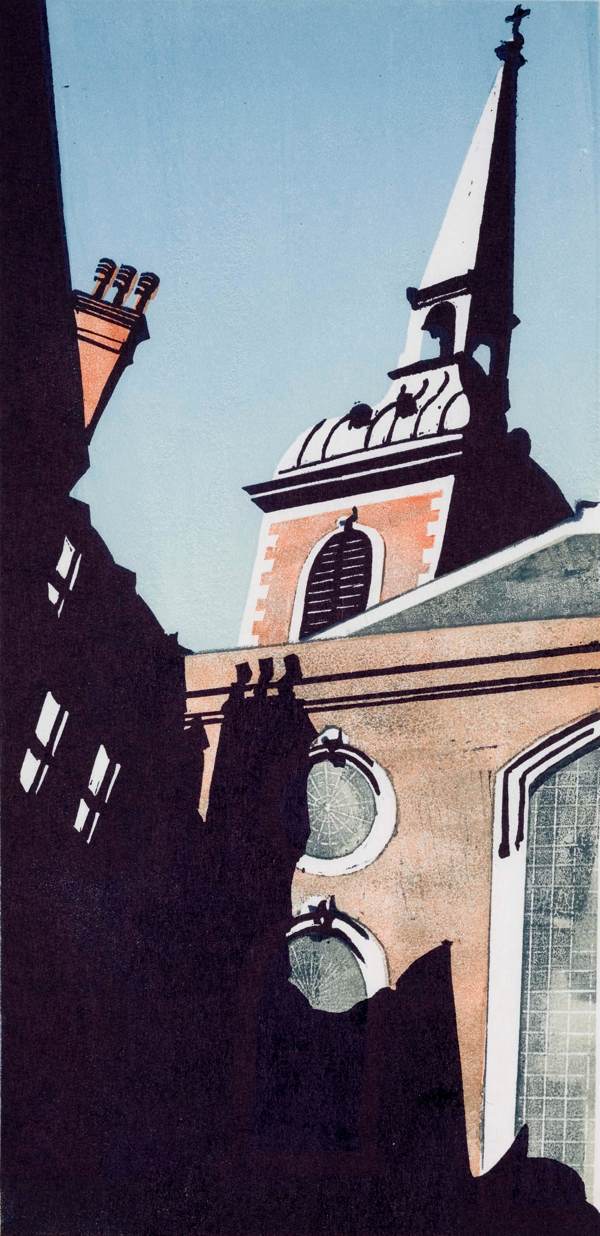

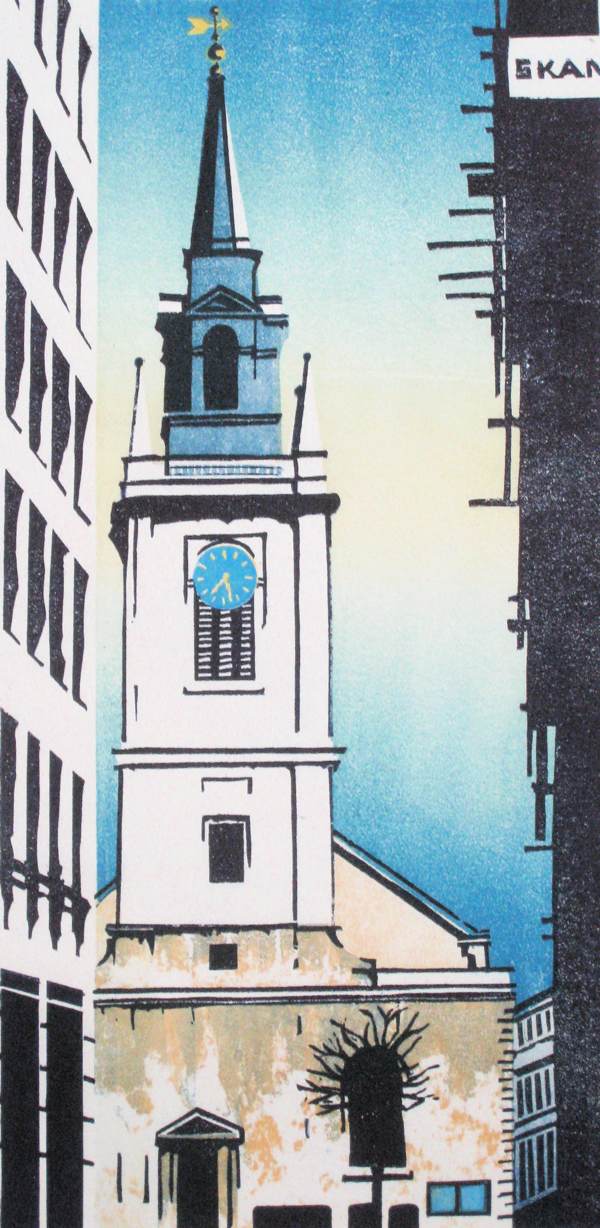

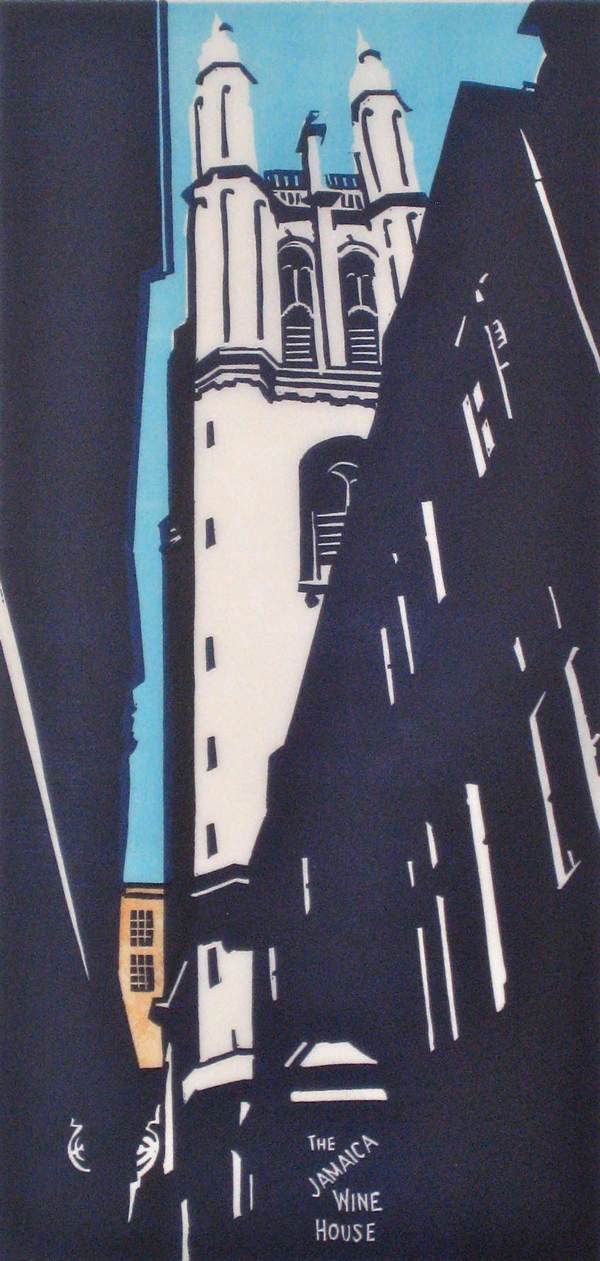

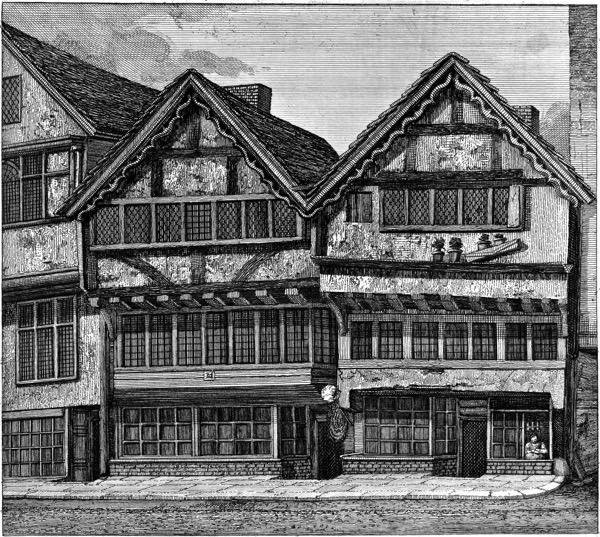

![L2082366]()

Blossom St

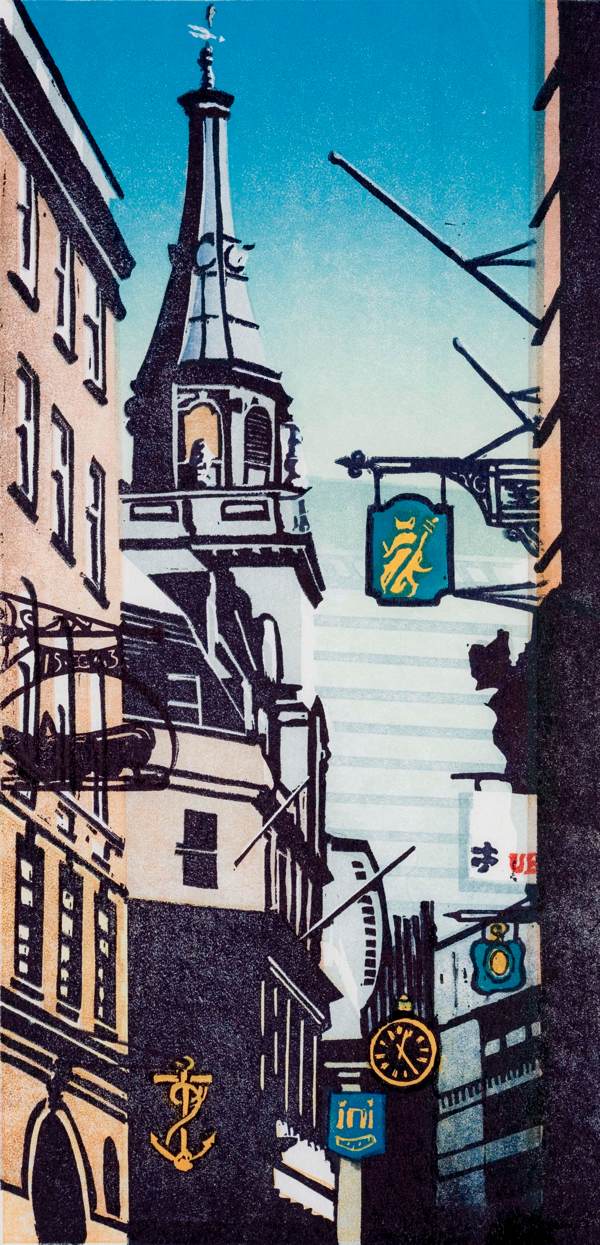

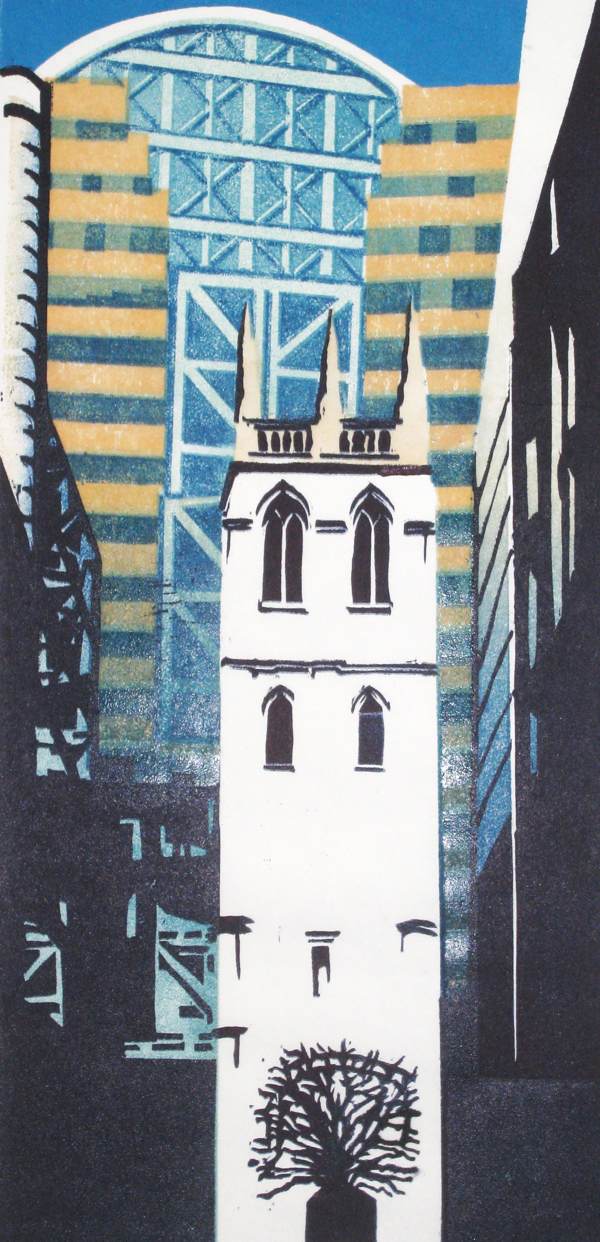

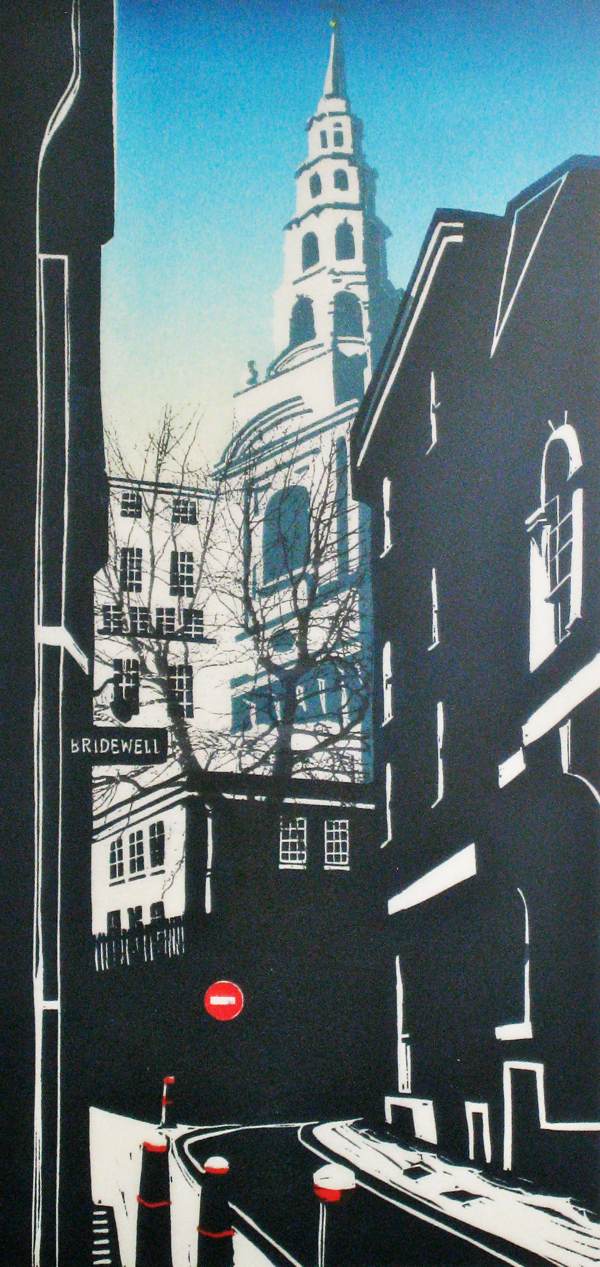

![L2082335]()

Star of David in Blossom St

![L2082329]()

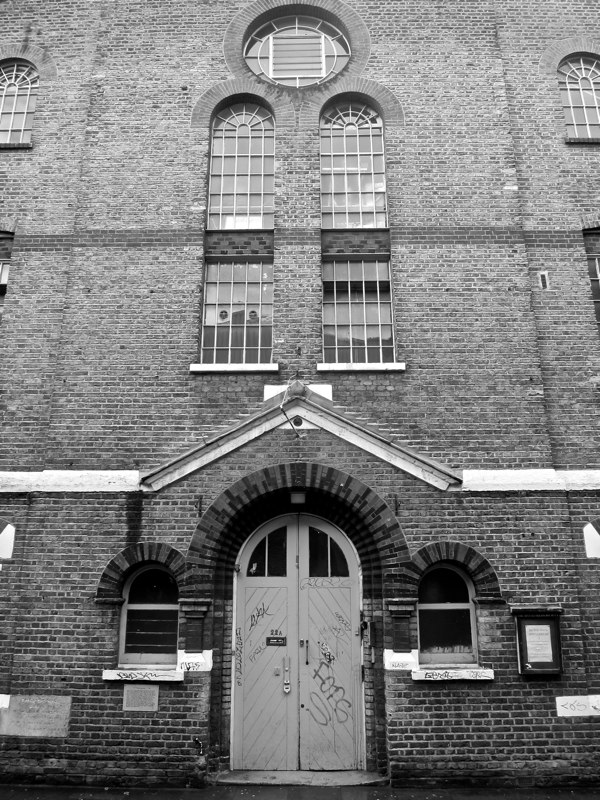

Elder St

![L2082321]()

Elder St

![L2082381]()

Elder St

![L2082386]()

Folgate St

![L2082376]()

Elder St

![L2082378]()

Corner of Elder St

![L2083183]()

Crochet courtesy of the Revolutionary Crafting Circle of Edinburgh

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

Take a walk around Norton Folgate with Dan Cruickshank

You may also like to take a look at

Inside the Nicholls & Clarke Buildings

The Ancient Curse of Norton Folgate

In Search of the Relics of Norton Folgate

In The Strand

In The Strand