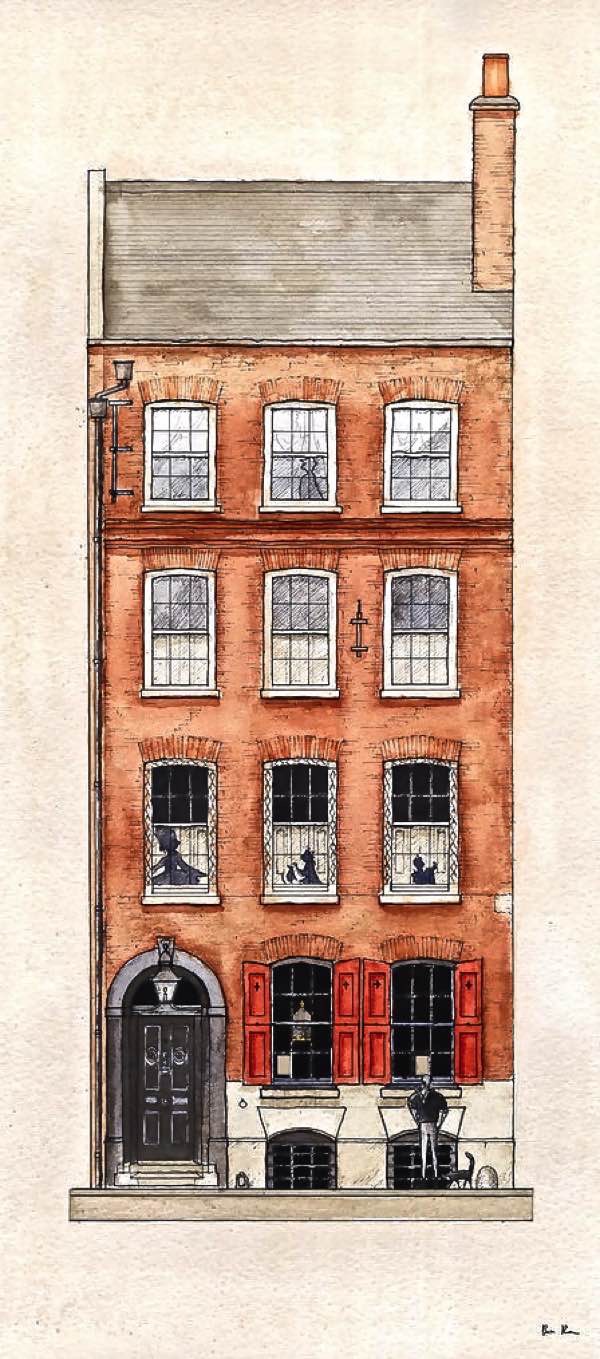

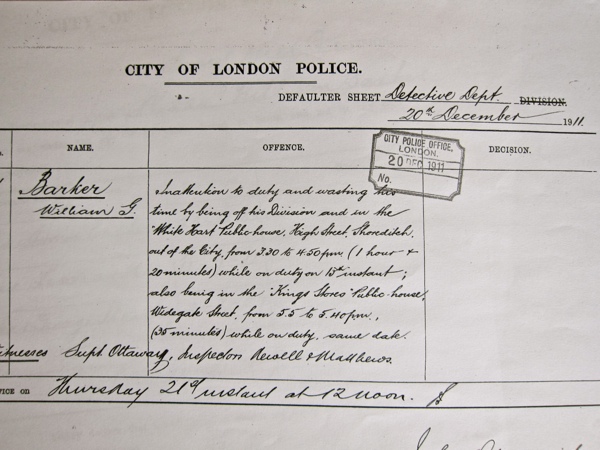

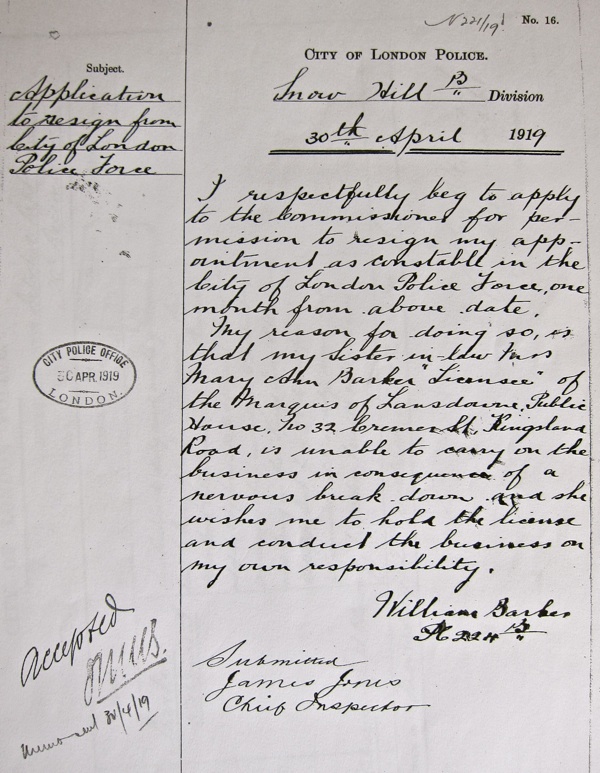

It is my great pleasure to unveil this bravura collaboration between Adam Dant, Cartographer Extraordinaire & Jonathon Green, Lexicographer of Slang – ARGOTOPOLIS is a map of London slang organised around relevant locations in the capital. Click on Adam’s map to study it in detail and read Jonathan’s glossary below to learn more about the language. A limited edition of 50 hand-tinted prints is available from TAG Fine Arts.

![adam 15.6.15 Scan]()

The Old Oak: rhyming slang, The Smoke, i.e. London

KEY TO THE SLANG WORDS & PHRASES IN ARGOTOPOLIS

compiled by Jonathon Green

.

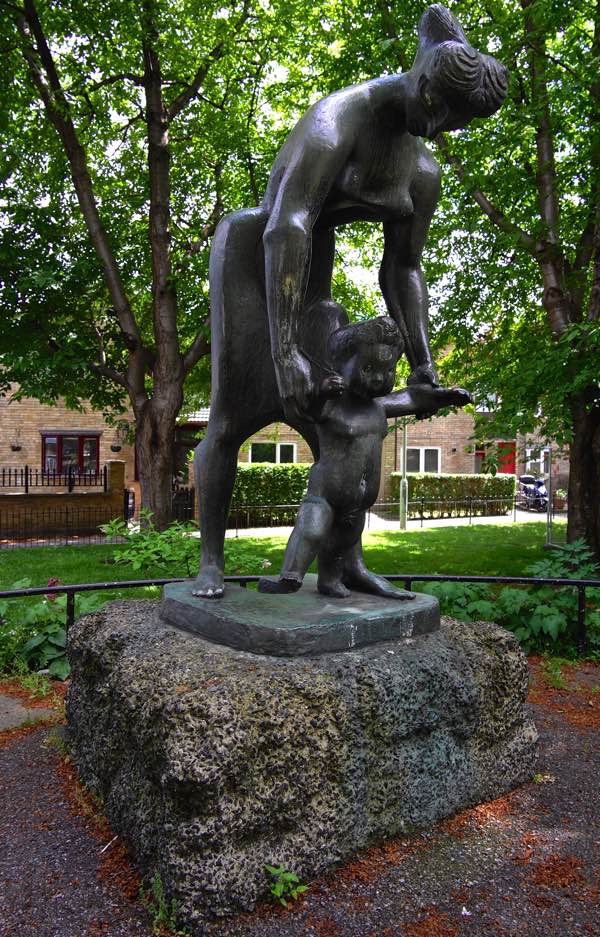

Nappy Valley (David Cameron’s House, Notting Hill)

Misses: Missus or Mrs

Armful: an affectionate spousal embrace

Bit o’ Tripe: possibly rhyming slang but possibly a ref. to the human body as a ‘piece of meat’

Burick: Romani burk, a breast or Scottish bure, a loose woman

Doner: Italian dona, a woman

Poker-breaker: the domineering wife’s ‘breaking’ of her husband’s poker, i.e. penis

’Pon My Life: rhyming slang, a wife

Rib: woman as ‘Adam’s rib’

Ankle-biter: a child who has yet to walk

Bin-Lid: rhyming slang, a kid

Gawdelpus: a child, lit. God help us

Chip: a child, i.e. a chip off the old block

Yuppie Puppy: the progeny of the young and upwards mobile; also trustafarian

Lully: a child, from little or lullaby

Swag: a shop

Buttiken: a shop, from French boutique + ken, a house or place

Drum: a house or home, either he image of the hollow drum resembling a hollow house or room or the use of drum, the road, as a figurative ‘house’ for itinerants.

Plate o’ Meat: rhyming slang, the street

Bricks: the city streets, especially as seen from a prison cell.

Stones: the streets of London, the open air

Carsey: a brothel, pub or lavatory, from Italian casa, a house

Crib: a house, a pub, a shop, a brothel, a cheap theatre, a bed, a safe, a cell, the vagina; all from standard crib, a narrow room

Gaff: a fair, a cheap theatre, a dancehall, a brothel, a prison, a house, a bar, a casino, a hotel; from Romani gav, a (market) town

.

Clobber (Selfridges, Oxford St)

Piccadilly Fringe: a popular women’s hairstyle in which the hair is cut short into a fringe and curled over the forehead

Piccadilly Weepers: long side whiskers, worn without a beard

Dittos: a suit of clothes (jacket, waistcoat, trousers) all the same colour

Bobtail: a dandy, from the wide skirts of his jackets

Gorger: a dandy, perhaps from gorgeous

Spiff: a dandy, from spiff, echoic of a sharp sound and thus figuratively exciting, important, astonishing

All Nations: a multi-coloured or heavily patched coat; from ‘the flags of all nations’.

Immensikoff: a large overcoat; coined by the music-hall star Arthur Lloyd who called himself Immensikoff and appeared on stage in such a coat to sing, c.1868, his hit ‘The Shoreditch Toff’

Spittleonian, a yellow silk handkerchief, manufactured in Spitalfields

Arse-Rugs: trousers

Sin-Hiders: trousers; they disguise the male genitals

Moab: a turban-shaped hat, worn by women; a jocular reference to Psalm 60: ‘Moab is my washpot’

Billycock: a style of man’s hat; perhaps a variation on bully-cocked, i.e. ‘cocked after the fashion of the bullies’ or pimps

Golgotha: a hat; pun on Greek golgotha, the place of skulls

Headlight, a large and ostentatious tie pin, usually a diamond one

Hopper-dockers / hock-dockies: shoes

Piccolo & Flute: rhyming slang, a suit.

Rig-Out: a costume; from nautical imagery: one’s clothes are one’s ‘rigging’

Cover-Me-Queerly: ragged clothing

Gropus: a pocket; one must grope into its depths to find small items

.

Yiddish (Sigmund Freud’s House, West Hampstead)

Goy: a gentile

Dreck: dirt

Fress: to eat

Kishkes: the intestines, the guts

Nudnik: a fool

Shpilkes: anxiety, nerves

Schnorrer: a beggar

Mozzle: luck

Plotz: to to lose emotional control

Bubbe Mayse: an old wife’s tale

.

Bogtrotters – Country Folk (Caravan, Outlying Rural London)

Carrot Muncher: the peasant’s staple diet

Clouted Shoon: lit. ‘a shoe tipped with iron and secured with iron nails’

Dog Booby: dog = male + booby = fool

Lob: dialect lob, a country bumpkin. Note Yiddish lobbes, a rascal and Dutch lobbes, a clown

Muck Savage: the idea that peasants are ‘savages’ living in filth

Nose Picker: a derogatory stereotype

Queer Cuffin: lit. ‘an odd bloke’

Sod Buster: the peasant’s agricultural labouring

Squab: SE squab, a raw, inexperienced person, also a young, unfledged bird or animal

Whopstraw: from whop, to hit; the work of threshing corn

.

Techies (Old St Roundabout)

Crapplet: a badly written or wholly useless app.

Angry Garden Salad: a poorly designed website GUI

Seagull Manager: (s)he flies in, craps all everything, then leaves

P.O.T.A.T.O.: “People Over Thirty Acting Twenty One’

Rasterbator: a designer who is obsessed with Photoshop

Salmon Day: a wasted day’s work: one has spent the entire day ‘swimming upstream’

Wall Humper: a person who, rather the removing the card from their pocket, raises their hip in an effort to swipe it against a reader

Open Your Kimono: to reveal one’s business plans

Grok: to understand fully, from Robert Heinlein’s scifi novel Stranger in a Strange Land

Ohnosecond: the fraction of time it takes to realize one has committed a major error

Chips and Salsa: chips refers to computer hardware, salsa to software

.

The Fancy – Boxing (York Hall, Bethnal Green)

Brother of the bunch of fives: a prize-fighter

Broughtonian : a prize-fighter; from Jack Broughton, inventor of the first prototype boxing glove, writer of ‘Broughton’s Rules’ (which lasted 1743–1838) and champion of England 1730–5

Bruiser: a prize-fighter

Whister-clister / Whister-poop: a blow to the ear

Clicker: a knock-out blow

Knight of the mawley: a prize-fighter, from mawley, a hand or fist

Fibbing-cull: a prize-fighter, from fib, to punch

Buckhorse: a blow to the ear

Jobber: a blow to the head

Smeller: the nose or a blow that hits it

Winker: a blow to the winkers, i.e. eyes

Slasher: a prize-fighter

Milling-kiddy: a prize-fighter, from mill, to fight

Breadbasketer or belly-go-firster : a blow to the stomach

Claret jug/ Claret cask / Claret-spout: the nose

.

Quackery (University College Hospital, Euston Square)

Nimgimmer: a surgeon or physician, esp. a specialist in venereal diseases

Knight of the Pisspot: a doctor, from the analysis of urine for medical purposes

Pintlesmith: a surgeon, lit. a ‘penis worker’

Crocus Pitcher: an itinerant quack doctor; also crocus (metallorum), a pun on croak, to die and crocus metallorum, oxysulphide of antimony

Twat Scourer: lit. the ‘cleaner of the vagina’

Flesh Tailor: a surgeon

Dr Drawfart: an itinerant quack doctor

Clyster Pipe: a doctor; lit. ‘a pipe used to administer clysters, or enemas’

Jollop, medicine, from jalap, a purgative drug obtained from the tuberous roots of Exogonium (Ipomoea) purga

Bone juggler: a surgeon

.

Argy-Bargy – Political Dissent (Marx Memorial Library, Clerkenwell)

Boodler: a corrupt politician, from boodle, bribes

Mud-pusher: a member of parliament, i.e. an M.P.

Quockerwodger: a politician who works for a patron rather than his/her constituents; lit. ‘a wooden puppet which can be made to ‘dance’ by pulling its strings

Lefty: a left-winger

Red: a radical; specifically a Bolshevik, a Communist; synonymous with communism since its birth in 1848

Rad / Raddie: a radical

Threepenny Masher: a young man who poses as a gentleman but lacks the savoir-faire, not to mention the funds.

Jack-Gentleman: a man of low birth or manners who has pretensions to be a gentleman, thus an insolent fellow, an upstart.

Macer: a swindler, from a possible link to mason, one who acquires goods fraudulently by giving a bill that they do not intend to honour

Swell Mobsman: a leading pickpocket, often undistinguishable from the smartly dressed people he robs

.

Nobs & Gentry (The Guildhall, City of London)

Gentry-cove: an aristocrat or gentleman

Swell cove: an aristocrat or gentleman

Snot: a gentleman, who is seen as snotty or arrogant

Tercel-gentle: a well-off knight or any rich gentleman, lit. a male falcon

Skyfarmer: a criminal beggar who tours the country posing as a gentleman farmer fallen on hard times, backed by suitably impressive, if counterfeit, papers

Queer Duke: an impoverished gentleman

Jagger: a (country) gentleman, from German Jäger, a sportsman

Rye mort / Rye mush: a gentleman or gentlewoman, from Romani rei a gentleman + mort, a woman or mush, a man

Nob / Nib: probably from nobility or nobleman

.

Hipsters (Tea Building, Shoreditch)

Amazeballs: wonderful

Bro Hug: a manly hug between two men who are friends

Cray: amazing, remarkable, lit. crazy

Humblebrag: self-deprecation actually used for self-aggrandizement

Throw shade: to talk negatively about a third party

Peeps: people

Rando: a random person or thing

That Wins the Internet: a general exclamation of satisfaction

Grill: the face

Rack: the female breasts

.

Americana (US Embassy, Grosvenor Sq)

Ham Shank: rhyming slang, a Yank or American

Man up: behave in a manly or macho manner

Grow a Pair: the pair are testicles, again one is encouraged towards a macho posture

Fanny Pack: a small satchel tied around one’s waist; from fanny, the buttocks

Heads-up: a warning, a briefing

Do the Math: work it out

Touch Base: to speak to

Septic: rhyming slang, a Septic Tank, a Yank or American

Can I Get…: rather than UK could I have

I’m Good: things are satisfactory, synonymous with UK response to ‘how are you’ of ‘very well thank you’

.

Park Life (Peter Pan Statue, Kensington Gardens)

Bumblebee: rhyming slang, a tree

Dr Green: the grass

Sleep with Mrs Green: to sleep in the open air

Ruffmans: a wood

Robin Hoods: rhyming slang, the woods

April Showers: rhyming slang, flowers

Eiffel Towers: rhyming slang, flowers

Skylark: rhyming slang, a park

Joan of Ark: rhyming slang, a park

Crackmans: a hedge

Lad: a fox

Charlie: a fox, pun on the politician Charles James Fox (1749–1806)

Bufe / Buffer: a dog, either echoic of a bark or from Welsh bwch, a buck, a male animal

Carpet-herb: grass

Old Iron and Brass: rhyming slang, the grass

Penny-a-Pound rhyming slang, the ground

.

Gambling (Crockfords Casino, Mayfair)

Blackleg: his black boots

Buttoner: that member of a gang who entices suckers to play in a crooked game; he buttonholes the victim

Topper-toodle: a gullible fool, esp. as prey to crooked gamblers

Thimble-Rigger: operator of a cheating game of ‘find-the-lady’ or the ‘three-card-trick’

Spieler: a casino, from Yiddish spiel, to play

Rump and a Dozen: the 18th century wager of a whole rumpsteak and a dozen bottles of claret

Punting-shop: a casino, from punt, to wager

Levanter: one who defaults on his debts, he lit. runs away to the Levant, i.e. the Middle East

Hazard-drum: a casino, from the game of hazard, a precursor of craps, and drum, a house

Grumble and Mutter: rhyming slang, a flutter

.

Whores (Soho Sq)

(All but one terms are simple synonyms for ‘ladies of the night’)

Frisker: from frisk, to have sexual intercourse

Cockatrice: in myth, a hybrid monster with head, wings and feet of a cock, terminating in a serpent with a barbed tai; such a monster can kill with a single glance

Ramp: from rampant, spirited

Trot: from trot, a hag, an old woman; she also ‘trots’ down the street

Trull: from German Trulle, a prostitute

Tib: supposedly a typical name for a working-class woman

Bluegown: prostitutes confined in a house of correction once wore a blue dress as their uniform

Circus Cowboy: a rent boy, who frequented the Piccadilly Circus ‘meat rack’

Covent Garden Nun: the popularity of Covent Garden as a centre of whoring

Quean: a specific use of a general term for a woman

Market Dame: the popularity of Covent Garden as a centre of whoring

Kate / Kittie: a generic use of the proper name

Miss Town: her role as a quintessentially urban figure

Town Miss: her role as a quintessentially urban figure

Miss o’ the Town: her role as a quintessentially urban figure

.

Old Jack Lang – Rhyming Slang (St Mary Le Bow, Cheapside, City of London)

Brixton Riot: a diet

Emma Freuds: haemorrhoids

Iron Hoof: a homosexual, i.e. a poof

Newington Butts: the stomach or guts

Queen Mum: the buttocks, i.e. the bum

Tony Blair: hair, a chair or a nightmare

Petticoat Lane: a pain

Charing Cross: a horse

Westminster Abbey: a cabbie

Alf Garnett: the hair, i.e. the barnet (fair)

.

Lucre ( The Bank of England, City of London)

Draft on the Pump at Aldgate: a fake bank-note or fraudulent bill; the Aldgate pump offered no financial security for a draft, i.e. a written order for the payment of money

Coriander (seed): a figurative use of seeds as form of growth and as such necessary for life; money has the same importance

Wedge: originally a wedge of silver

Readies: i.e. ready money

Scrilla: possible from a scroll, on which accounts were once kept

Sponds: fom Greek spondlikos, i.e. spondulics

Mazuma: from Yiddish, ultimately Hebrew mazuma, prepared, ready

Gelt: from Yiddish and German, gold

Dosh: from doss, to sleep or a bed; thus originally the money required to pay for one’s accommodation

Bread: the ‘staff of life’, as is money

.

Rookeries – New Office Blocks (1 Old St Mary’s Axe, City of London)

Can of Ham: 60-70 St Mary’s Axe

Armadillo: City Hall

Walkie-Talkie: 20 Fenchurch St

Cheesegrater: Leadenhall Building

Pringle: the Olympic Cycle Track

Helter-Skelter: the Pinnacle Tower

The Prawn: Willis Building

Stealth Bomber: 1 New Change

Gherkin / Wally: 30 St Mary Axe

Shard: 32 London Bridge Street

.

Toffs (Buckingham Palace)

NQOCD: Not Quite Our Class, Darling

NSIT: Not Safe in Taxis

PLU: People Like Us

MTF: Must Touch Flesh

SOHF: Sense of Humour Failure

Yonks: a long time

Jew canoe: a large car, often a Jaguar

Killing: uproariously amusing

Gucky: the fashion label Gucci

Cockers-p: a cocktail party

Chateaued: drunk, not necessarily on claret

Wrinklies: old people

Stiffie: an invitation

Brill: brilliant

.

Nosh (Covent Garden Market)

Ozzimangerum, soup made from a leg of beef; from ox + French manger, to eat

Princess Di: rhyming slang, a pie

Fourpenny Cannon: a steak and kidney pie; the cost plus its supposed resemblance to a cannonball

Bags of Mystery: sausages, the specific meat ingredient is not specified by the seller

Alderman in Chains: a roast turkey garlanded in sausages

Banger: a sausage, which may explode in the pan

Sharp’s Alley Bloodworms: beef sausages or black puddings, from Sharp’s Alley, an abattoir near the Smithfield meat market in London]

Darby Kelly: rhyming slang, the belly

Chamber of Horrors: sausages

Zeps in a Cloud: sausage and mash

Sanguinary James / Bloody Jemmy / One-eyed Joint: an uncooked sheep’s head

Poodle: a sausage, a pun on hot dog

Irish Apricots: potatoes, the stereotyped link of the Irish and the potato

Violets: spring onions or sage and onion stuffing

Horn Root: celery, it is supposedly aphrodisiac

Welsh Turkey: a leek, the stereotyped link of the Welsh and leeks

Rose: an orange, possibly the fruit also has a pleasant smell

Whitechapel: rhyming slang, an apple

Teddy Bear: rhyming slang, a pear

Snob’s duck, a baked sheep’s head (which is far cheaper than a real duck)

Thames Butter: completely rancid butter, the ‘South London Press …published a paragraph to the effect that a Frenchman was making butter out of Thames mud at Battersea. In truth this chemist was extracting yellow grease from Thames mud-worms’

.

The Uproar (Covent Garden Opera House)

Synagogue: a shed – its use is not specified – standing at that time in the northeast corner of Covent Garden, London.

The Straights: a network of alleyways and small courts in an area bounded by St Martin’s Lane, Half Moon Street and Chandos Street, the haunt of pimps, thugs and similar unsavoury characters.

Short’s Gardens: a state of temporary penury; a pun on the street Short’s Gardens in Covent Garden and short, impoverished

Mutton Walk: the saloon at the Drury Lane Theatre, Covent Garden; thus any street where one finds prostitutes, especially the junction of Coventry Street and Windmill Street in the West End.

The Finish / Carpenter’s Coffee Shop: Carpenter’s late-night coffee shop, sited in Covent Garden opposite Russell Street and ostensibly catering to the market porters, which closed only when the last customer had gone home into the dawn

Go Shop: the Queen’s Head tavern, Duke’s Court, Bow Street, London WC2.

The Lane: Petticoat Lane, Middlesex Street in the east End; Drury Lane, Covent Garden, in the West End

Break One’s Shins Against Covent Garden Rails:

Russian Coffee House: the Brown Bear public house in Bow Street, Covent Garden, a popular haunt for both thieves and thief-takers.

Tekram: backslang for Covent Garden market

.

Hoorays (Chelsea Town Hall)

Maybs: maybe

Blates: blatantly

Defo: definitely

Dorbs / Adorbs: adorable

Totes: totally

Soz: sorry

Probs: probably

Presh: precious

Obvs: obviously

OMG!: Oh my God!

.

Slicksters (Houses of Parliament, Westminster)

Craftsby: a cheat, a swindler

Swindling gloak: a swindler; gloak is synonymous with bloke, a fellow

Dunlop tyre: rhyming slang, a liar

Holy friar: rhyming slang, a liar

Cony-catcher: a confidence trickster, from cony, a rabbit, i.e. a sucker

Queer plunger: a confidence trickster who plunges into water and is saved from ‘drowning’; conveniently pre-assembled ‘rescuers’ then claim money for saving the person

Tweedler: a small-time confidence trickster; a stolen vehicle that is passed off a legitimate

Nuxyelper: a confidence trickster who fakes a fit in order to gain money from bystanders; from nux vomica, the fruit from which strychnine is produced, and which would induce vomiting

Jack-in-the-box: a street pedlar who specialises on con tricks

Shearer: a confidence trickster, who ‘shears’ the gullible ‘lamb’

.

The Law (Royal Courts of Justice, Fleet St)

China Street Pig: a Bow Street Runner

Thieves’ Kitchen: the Law Courts in the Strand

Theatre: a police, later magistrate’s court

Tenterden Park: the King’s Bench prison for debtors

Gentleman of the Three In(n)s : one who is in debt, in goal and in danger (of being hanged)

Fortune-teller / Conjuror: a judge, he ‘tells one’s future’

Ambidexter: a lawyer, he holds out both hands for bribes

Honest lawyer: a public house sign showing a headless man dressed in lawyer’s robes, the implication being that his honesty is only possible since, headless, he is bereft of the chance to speak.

.

God Box (St Paul’s Cathedral)

(All terms mean a clergyman, with an over-riding image of thumping the bible or pulpit)

Amen-Bawler

Bead Counter: the rosary beads

Smell-Smock: the clergyman’s alleged womanising

Mumble-Matin[s]

Black cattle: clergymen as a group

Soul Doctor / Soul Driver

Hum-Box Patterer: the hum-box is a pulpit

Cackletub: the tub is a pulpit

Good Book Thumper

Autem Cove / Pattering Cove: from autem, probably an altar, pattering, sermonising

.

Fur-men (Mansion House, City of London)

Bus-Bellied Ben: an alderman who ‘eats enough for ten’

City Bulldog: a constable

Lord Mayor: a large crowbar

Farmer: an alderman, from farm, to lease or let the proceeds or profits of customs, taxes etc. for a fixed payment

Alderman Lushington: a drunkard

Alderman’s Pace: a steady, careful pace, as befits an official with a fine sense of his own importance

Alderman Double Slang’d: a roast turkey garlanded with sausages

Recorder’s Nose: the rump of a chicken, duck, goose or other poultry.

City Wire: a fashionable woman; her use of wire to create elaborate hairstyles

Cit: a citizen, especially a merchant of the City of London

.

Brassic – Poverty (former Whitechapel Library, Aldgate East)

Pov / Povvo: an impoverished person.

Stig: a tramp or someone who resembles a tramp

Ding: a beggar, a tramp

Downrighter: a beggar, a tramp

Cursetor: a tramp or an impoverished lawyer

Fleabag: one who smells, usually a vagrant

Crank Cuffin: a tramp who poses as a sufferer from a sympathy-inducing illness

Abrahamer: a tramp, usually sporting picturesque rags to attract alms

Smelly Welly: a juvenile pejorative for a poor person who is seen as a tramp

Dosser: a tramp, a vagrant, a homeless person., from doss, to sleep (rough)

.

Cold Meat – Execution (Tower of London, Tower Hill)

Do the Newgate Frisk: from Newgate, outside public hangings took place from 1783-18688

Paddington Spectacles: the sack which is placed over the prisoner’s head prior to the hanging

Jig upon Nothing: the ‘dancing’ of the dying person’s feet as they choke to death

Climb the Leafless Tree: one of the many equations of the gallows with a ‘tree’

Have a Wry Mouth and Pissen Britches: a dry mouth and involuntary urination accompany one’s being hanged

City Stage: on which the guilty person ‘performs’

City Scales: the guilty man or woman is weighed off, i.e. sentenced and executed

Dance at Beilby’s Ball Where the Sheriff Pays the Fiddlers: the identity of Mr Beilby is unknown but a number of suggestions exist. [1] Beilby was a well-known sheriff; [2] Beilby is a mispronunciation of Old Bailey, the court in which so many villains were sentenced to death. [3] Beilby refers to the bilbo, a long iron bar, furnished with sliding shackles to confine the ankles of prisoners and a lock by which to fix one end of the bar to the floor or ground. Bilbo comes from the Spanish town of Bilbao, where these fetters were invented

Swing on Tyburn Tree: the Tyburn gallows at the west end of what would become Oxford Street, used for executions 1388–1783

Do the Paddington Frisk: Paddington was synonymous with Tyburn, original site of the main London gallows.

.

Terms for Places listed on the Tree Trunk

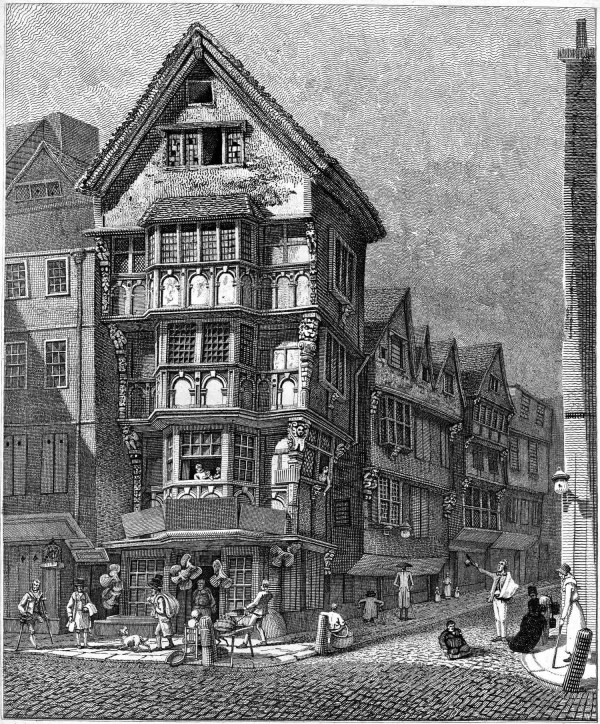

Alsatia: the 16th century ‘liberty’ south of Fleet Street, a law-free zone wherein crowded every fugitive villain

Black Mary’s Hole: a 17th century gay cruising ground in Clerkenwell, EC1

Cheape: Cheapside

Dilly: Piccadilly

Elephant; Elephant and Castle

Fleet: the river Fleet or Fleet Street

Garden: Covent Garden and its Market

Holy Land: the criminal rookery (i.e. slum) of St Giles (now the site of Centre Point)

In and Out; the Army & Navy Club, Piccadilly (from its doorposts which were thus painted)

Junction: Clapham Junction

Kangaroo Valley: Earl’s Court, once home of ex-patriate Australians

Lane: Petticoat Lane, focus of the Jewish East End

Mohocks: a gang of dissolute upper-class thugs, flourishing c. 1750

Newgate: London’s main prison, now the Central Criminal Court at the Old Bailey

Old Nask: Bridewell prison, Tothill Fields

Paddy’s Goose; a notoriously violent sailor’s pub on the Ratcliffe Highway

Queer Street: a figurative term for poverty

Recent Incision: the New Cut, Waterloo

Spittal: Spitalfields

Tyburn: London’s original execution ground, now Marble Arch

Up-West: the West End

Ville: Pentonville Prison, north London

Wanno: Wandsworth Prison, south London

X: Charing Cross

Yard: the police headquarters of Scotland Yard

Zoo: The Zoological Gardens, now London Zoo

![adam 15.6.15 Scan]()

Map copyright © Adam Dant

Text copyright © Jonathan Green

You may also like to take a look at

Jonathan Green’s Smithfield Slang

Adam Dant’s Map Of The Coffee Houses

The Meeting of the New & Old East End in Redchurch St

Redchurch St Rake’s Progress

Map of Hoxton Square

Hackney Treasure Map

Map of the History of Shoreditch

Map of Shoreditch in the Year 3000

Map of Shoreditch as New York

Map of Shoreditch as the Globe

Map of Shoreditch in Dreams

Map of the History of Clerkenwell

Map of the Journey to the Heart of the East End

Map of the History of Rotherhithe

Map of Industrious Shoreditch

Adam Dant’s Map of Walbrook

Windsor border trials

Windsor border trials