![Hair Brooms]()

Brushseller outside Shoreditch Church by William Marshall Craig, 1804

For centuries, the most popular prints in the capital were the Cries of London. From the Elizabethan era onwards, these lively images were treasured by Londoners, celebrating the familiar hawkers and pedlars of the city. Those who had no job or shop or market stall could always make a living by selling wares in the street and, by turning their presence into a performance through song, they won the hearts of generations and came to embody the spirit of London itself.

This November – if I can gather enough investment from readers of Spitalfields Life - I plan to publish a beautiful book designed by David Pearson which will be the first major visual survey of this important cultural tradition of the London streets. The Gentle Author’s Cries of London will assemble a diverse selection of the best examples, telling the stories of the artists and the most celebrated traders, and revealing the unexpected social realities contained within these cheap colourful prints produced for the mass market.

To coincide with the publication of The Gentle Author’s Cries of London, I am delighted to be collaborating with Spitalfields Music who are opening their Winter Festival with a concert in St Leonard’s, Shoreditch, of music from old songbooks of the Cries of London, while the Bishopsgate Institute will be be staging a cultural festival around the theme of street trading, including a pedlars’ conference and an exhibition of fine examples of Cries of London from their archive.

Samuel Pepys collected sets of Cries of London both from his own day and a century earlier, and I believe he was the first writer to recognise that they comprised a significant social record. Over the past five years, I have been publishing sets of Cries of London in the pages of Spitalfields Life and grown fascinated by these wonderful images and the stories they tell of the lives of Londoners down the centuries.

Drawing upon hundreds of interviews I have undertaken, The Gentle Author’s Cries of London concludes with a survey of the situation for traders and pedlars in London today, and reflects upon the aged-old ambivalence with which those who seek to make a living in the street are viewed.

Below, I publish my account of William Marshall Craig’s ‘Intinerant Traders in Their Ordinary Costume’ from 1804 as a taster of the book.

As with previous titles I have published, I need to gather enough readers who are willing to invest £1000 each to make it possible. Please email Spitalfieldslife@gmail.com if you would like to help me publish The Gentle Author’s Cries of London and I will send you further information.

![A Showman]()

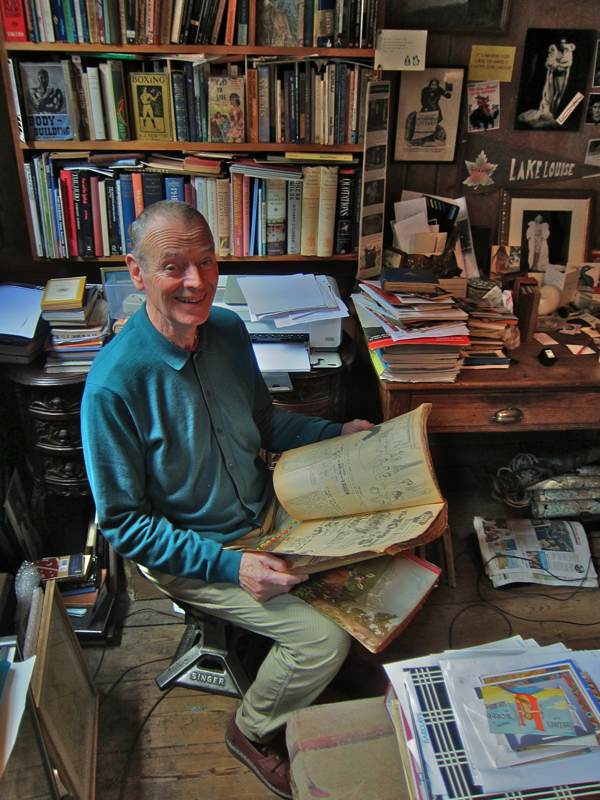

As fresh as the day they were hand-tinted in 1804, these plates from William Marshall Craig’s “Itinerant Traders of London in their Ordinary Costume, with Notices of Remarkable Places given in the Background” were discovered bound into the back of another volume at the Bishopsgate Institute in Spitalfields, and the vibrancy of their pristine hues suggests they have never been exposed to daylight in two centuries.

Yet, in contrast to their colourful aesthetic, these fascinating prints are often unexpectedly revealing of the reality of the lives of the dispossessed and outcast poor who sought a living upon the streets as hawkers at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Look again at the showman in the gaudy uniform with the peep show in the turquoise box and the red squirrel in a wheel – in fact, this reserved gentleman is a veteran who has lost a leg in the war. Observe the plate below of the woman in Soho Square feeding her baby and minding a bundle of rushes while her husband seeks chairs to mend in the vicinity, she looks careworn.

A fashionable portrait artist who exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1788 and 1827, William Marshall Craig was appointed painter in watercolours to Queen Charlotte, and in this set of prints he dignifies the itinerant traders by including some unsentimental portraits of individuals, allowing them self-possession even as they proffer their wares in eager expectation of a sale. In his drawings, engraved onto thirty-one plates by Edward Edwards, he shows tenderness and human sympathy, acknowledging the dignity of working people in portrayals that admit the vulnerability and occasional weariness of those who woke in the dawn to spend their days trudging the streets, crying their wares in all weathers. Despite their representation with rosy cheeks and clothes of pantomime prettiness, we can see these are street-wise professionals – born survivors – who could turn a sixpence as easily as a penny and knew how to scratch a living out of little more than resourcefulness.

William Marshall Craig’s itinerants exist in a popular tradition of illustrated prints of the Cries of London which began in the seventeenth century, preceded by verse such as “London Lackpenny,” attributed to the fifteenth century poet John Lydgate, recording an oral culture of hawkers’ cries that is as old as the city itself. In the twentieth century, the “Cries of London” found their way onto cigarette cards, chocolate boxes and, famously, tins of Yardley talcum powder, becoming divorced from the reality they once represented as time went by, copied and recopied by different artists.

The sentimentally cheerful tones applied by hand to William Marshall Craig’s prints, that were contrived to appeal to the casual purchaser, chime with the resilience required by traders selling in the street. And it is our respect for their spirit and resourcefulness which may account for the long lasting popularity of these poignant images of the self-respecting poor who turned their trades into performances. By making the streets their theatre, they won the lasting affections of generations of Londoners in the process, and came to manifest the very soul of the city itself. Even now, it is impossible to hear the cries of market traders and newspaper sellers without succumbing to their spell, as the last reverberations of a great cacophonous symphony echoing across time and through the streets of London.

Yet there is contradictory side to this affection. Equally, street traders have always been perceived as socially equivocal characters with an identity barely distinguished from vagabonds. The suspicion that their itinerant nature facilitated thieving and illicit dealing, or that women might be selling their bodies as as well as their legitimate wares, has never been dispelled. It is a tension institutionalised in this country through the issuing of licences, criminalising those denied such official endorsement, while on the continent of Europe the right to sell in the street is automatically granted to every citizen.

William Marshall Craig placed each of his itinerants within a picturesque view of London, thus giving extra value to the buyer by simultaneously celebrating the wonders of architectural development as well as the infinite variety of street traders. But there is a disparity between the modest humanity of the hawkers and the meticulously rendered monumentalism of the city. These characters are as out of place as those unreal figures in artists’ impressions of new developments, placed there to sell the latest scheme. Even as the noble buildings and squares of Georgian London speak of the collective desire for social order, the presence of the hawkers manifests a delight in human ingenuity and the playful anarchy of those who come singing through the streets. Depending upon your point of view, the itinerants are those who bring life to the city through their occupation of its streets or they are outcasts who have no place in a developed modern urban environment.

Yet none can resist the romance of the Cries of London and the raffish appeal of the liberty of vagabondage, of those who had no indenture or task master, and who travelled wide throughout the city, witnessing the spectacle of its streets, speaking with a wide variety of customers, and seeing life. In the densely-populated neighbourhoods, it was the itinerants’ cries that marked the times of day and announced the changing seasons of the year. Before the motorcar, their calls were a constant of street life in London. Before advertising, their songs were the announcement of the latest, freshest produce or appealing gimcrack. Before radio, and television, and internet, they were the harbingers of news, and gossip, and novelty ballads. These itinerants had nothing but they had possession of the city.

William Marshall Craig’s prints reveal that he understood the essential truth of London street traders, and it is one that still holds today – they do not need your sympathy, they only want your respect, and your money.

![Chairs to Mend]()

Chairs to mend. The business of mending chairs is generally conducted by a family or a partnership. One carries the bundle of rush and collects old chairs, while the workman seating himself in some convenient corner on the pavement, exercises his trade. For small repairs they charge from fourpence to one shilling, and for newly covering a chair from eighteen pence to half a crown, according to the fineness of the rush required and the neatness of the workmanship. It is necessary to bargain for price prior to the delivery of the chairs, or the chair mender will not fail to demand an exorbitant compensation for his time and labour.(Soho Sq, a square enclosure with shrubbery at the centre, begun in the time of Charles II.)

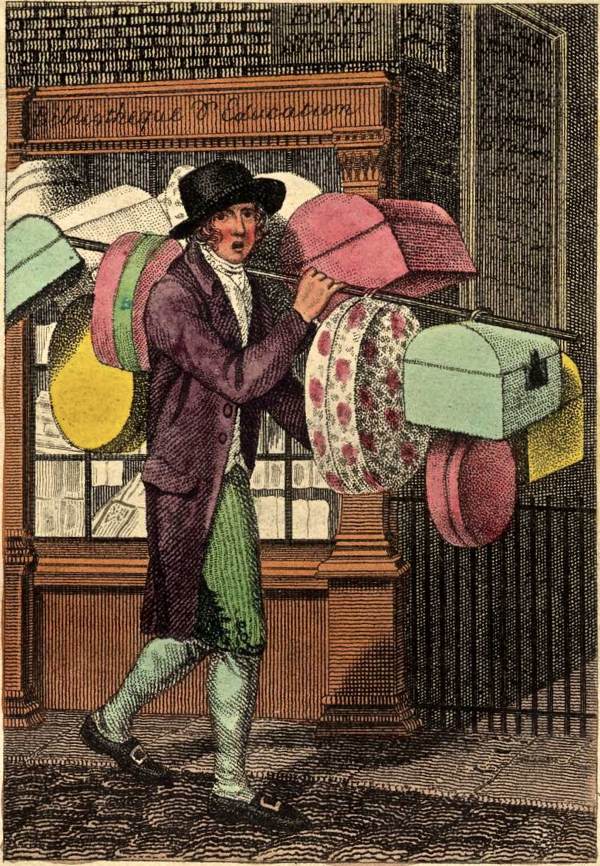

![Band Boxes]()

Band boxes. Generally made of pasteboard, and neatly covered with coloured papers, are of all sizes, and sold at every intermediate price between sixpence and three shillings. Some made of slight deal, covered like the others, but in addition to their greater strength having a lock and key, sell according to their size, from three shillings and sixpence to six shillings each. The crier of band boxes or his family manufacture them, and these cheap articles of convenience are only to be bought of the persons who cry them through the streets. (Bibliotheque d’Education or Tabart’s Juvenile Library is in New Bond St.)

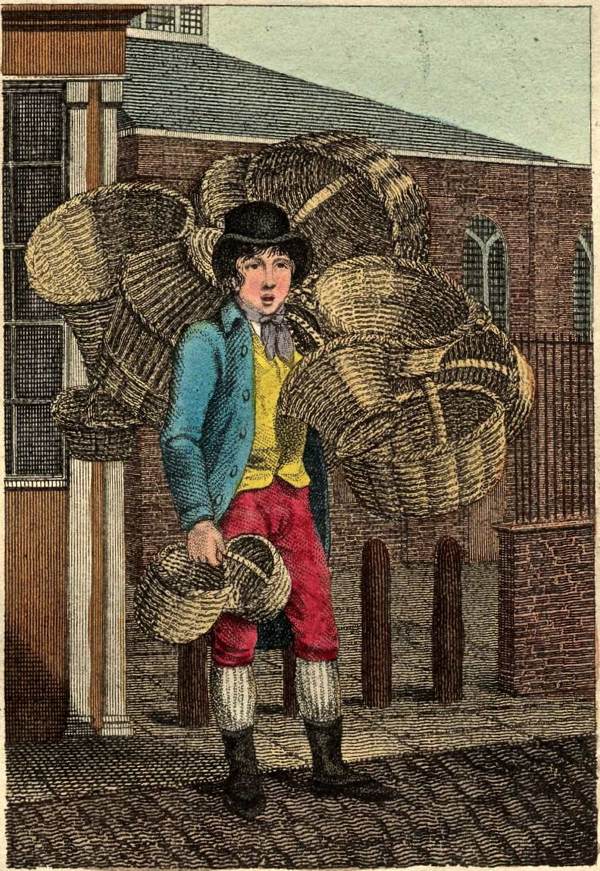

![Baskets]()

Baskets. Market, fruit, bread, bird, work and many other kinds of baskets, the inferior rush, the better sort of osier, and some of them neatly coloured and adorned, are to be bought cheaply of the criers of baskets. (Whitfield’s Tabernacle, north of Finsbury Sq, is a large octagon building, the place of worship belonging to the Calvinistic methodists.)

![Bellows to Mend]()

Bellows to mend. The bellows mender carries his tools and apparatus buckled in a leather bag to his back, and, like the chair mender, exercises his occupation in any convenient corner of the street. The bellows mender sometimes professes the trade of the tinker. (Smithfield where the great cattle market of London is held, on which days it is disagreeable, if not dangerous to pass in the early part of the day on account of the oxen passing from the market, on whom the drovers sometimes exercise great cruelty.)

![Brick Dust]()

Brick Dust is carried about the metropolis in small sacks on the backs of asses, and is sold at one penny a quart. As brick dust is scarcely used in London for any other purpose than that of knife cleaning, the criers are not numerous, but they are remarkable for their fondness and their training of bull dogs. This prediliction they have in common with the lamp lighters of the metropolis. (Portman Sq stands in Marylebone. In the middle is an oval enclosure which is ornamented with clumps of trees, flowering shrubs and evergreens.)

![Buy a Bill of the Play]()

Buy a bill of the play. The doors of the London theatres are surrounded each night, as soon as they open, with the criers of playbills. These are mostly women, who also carry baskets of fruit. The titles of the play and entertainment, and the name and character of every performer for the night, are found in the bills, which are printed at the expense of the theatre, and are sold by the hundred to the criers, who retail them at one penny a bill, unless fruit is bought, when with the sale of half a dozen oranges, they will present their customer a bill of the play gratis. (Drury Lane Theatre, part of the colonnade fronting to Russell St, Covent Garden.)

![Cats and Dogs Meat!]()

Cats’ & dogs’ meat, consisting of horse flesh, bullocks’ livers and tripe cuttings is carried to every part of the town. The two former are sold by weight at twopence per pound and the latter tied up in bunches of one penny each. Although this is the most disagreeable and offensive commodity cried for sale in London, the occupation seems to be engrossed by women. It frequently happens in the streets frequented by carriages that, as soon as one of these purveyors for cats and dogs arrives, she is surrounded by a crowd of animals, and were she not as severe as vigilant, could scarcely avoid the depredations of her hungry followers. (Bethlem Hospital stands on the south side of Moorfields. On each side of the iron gate is a figure, one of melancholy and the other of raging madness.)

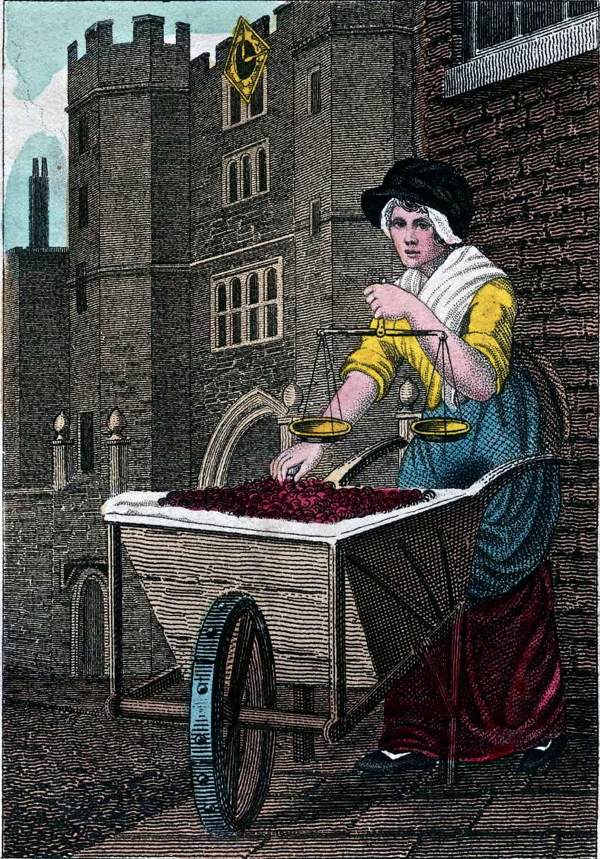

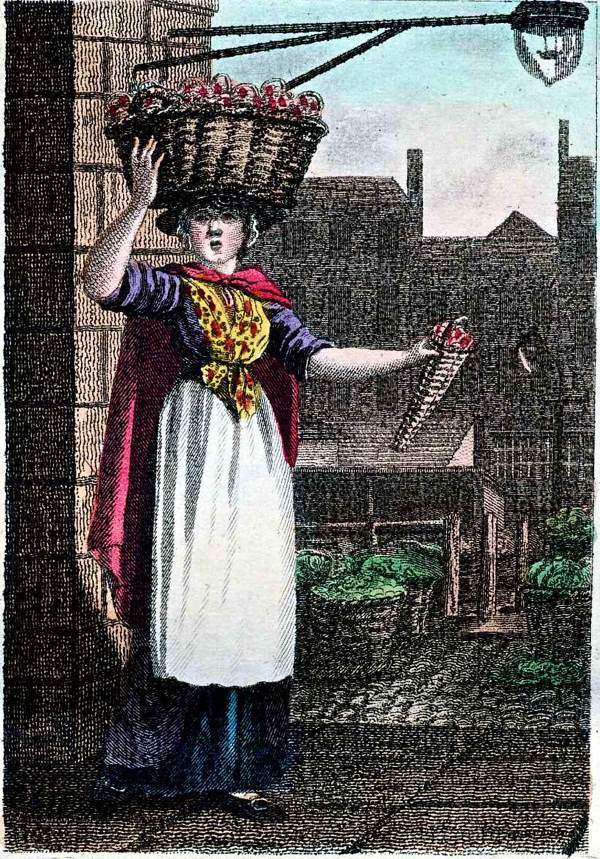

![Cherries]()

Cherries appear in London markets early in June, and shortly afterwards become sufficiently abundant to be cried by the barrow women in the streets at sixpence, fourpence, and sometimes as low as threepence per pound. The May Duke and the White and Black Heart are succeeded by the Kentish Cherry which is more plentiful and cheaper than the former kinds and consequently most offered in the streets. Next follows the small black cherry called the Blackaroon, which is also a profitable commodity for the barrows. The barrow women undersell the shops by twopence or threepence per pound but their weights are generally to be questioned, and this is so notorious an objection that they universally add “full weight” to the cry of “cherries!” (Entrance to St James’ Palace, its external appearance does not convey any idea of its magnificence.)

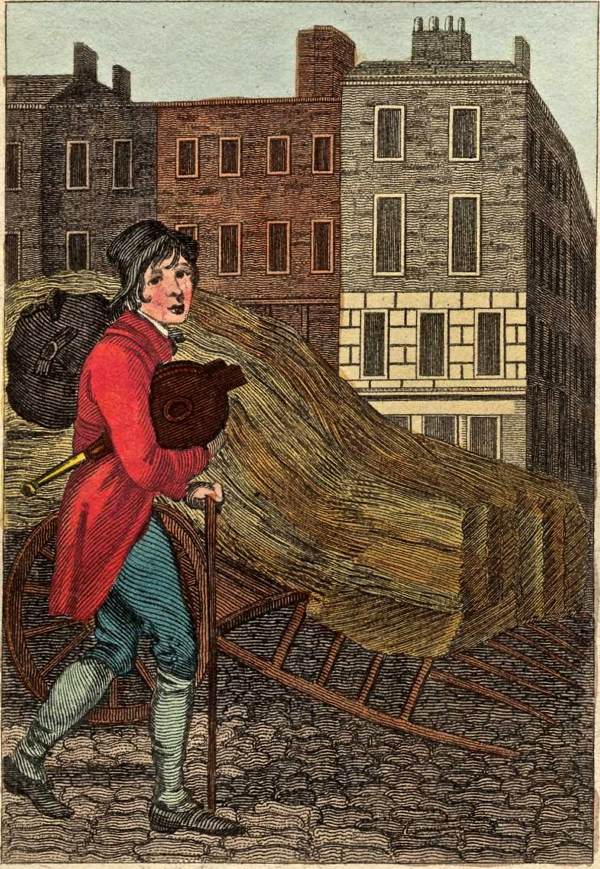

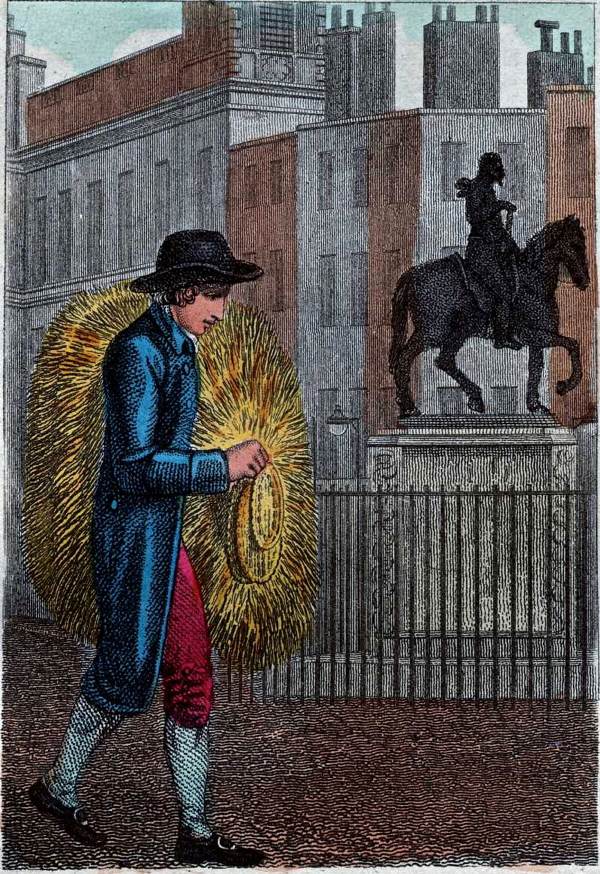

![Door Mats]()

Doormats, of all kinds, rush and rope, from sixpence to four shillings each, with table mats of various sorts are daily cried through the streets of London. (The equestrian statue in brass of Charles II in Whitehall, cast in 1635 by Grinling Gibbons, was erected upon its present pedestal in 1678)

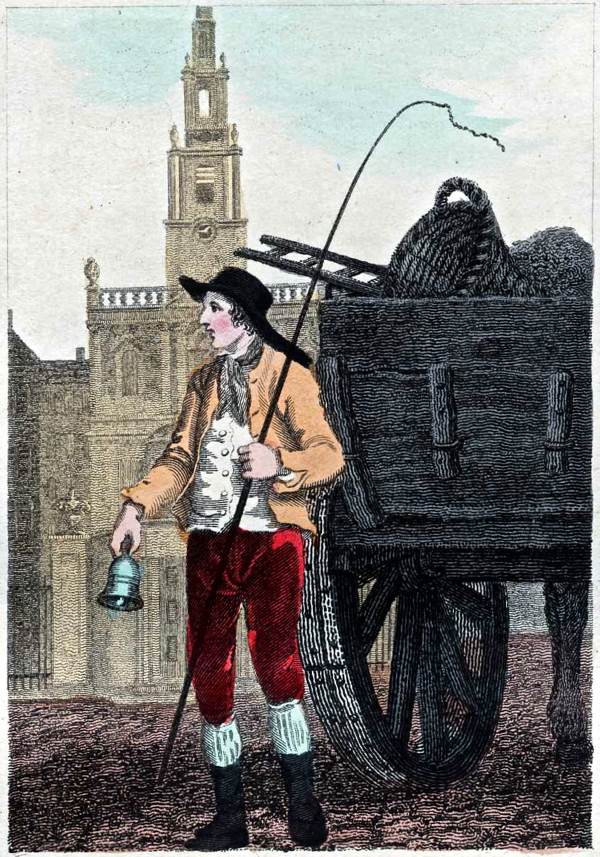

![Dust O!]()

Dust O! One of the most useful, among the numberless regulations that promote the cleanliness and comfort of the inhabitants of London, is that which relieves them from the encumbrance of their dust and ashes. Dust carts ply the streets through the morning in every part of the metropolis. Two men go with each cart, ringing a large bell and calling “Dust O!” Daily, they empty the dust bins of all the refuse that is thrown into them. The ashes are sold for manure, the cinders for fuel and the bones to the burning houses. (New Church in the Strand, contiguous to Somerset House and dividing the very street in two.)

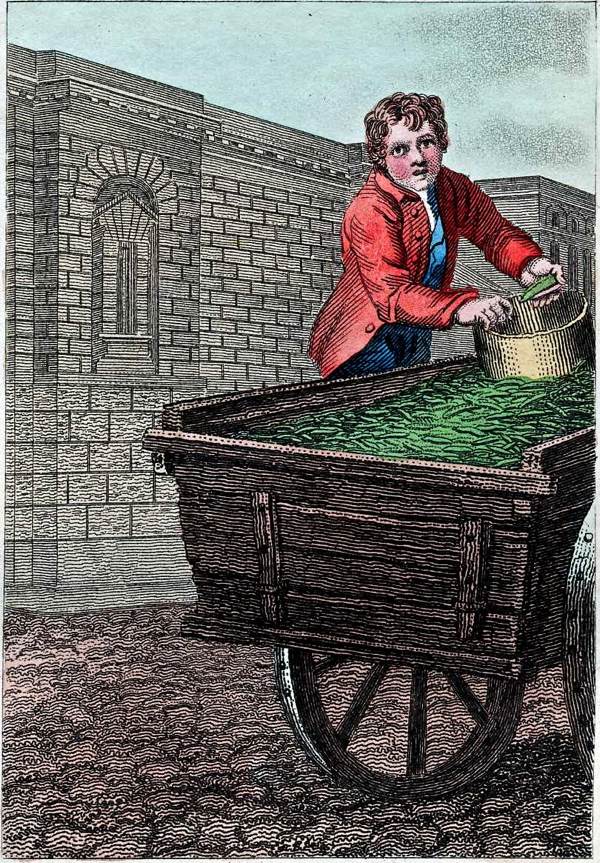

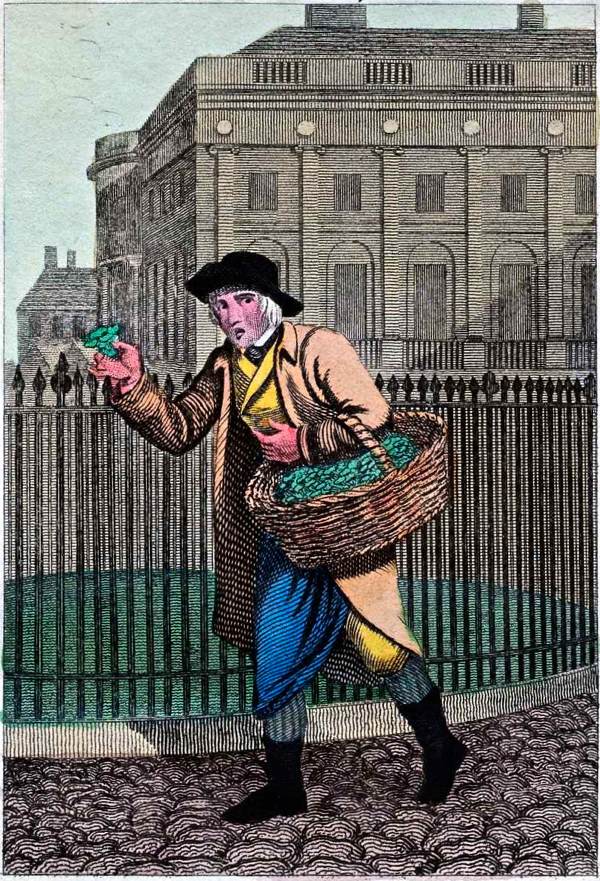

![Green Hasted!]()

Green Hastens! The earliest pea brought to the London market is distinguished by the name of “Hastens,” it belongs to the dwarf genus and is succeeded by the Hotspur. This early pea, the real Hastens, is raised in hotbeds and sold in the markets at the high price of a guinea per quart. The name of Hastens is however indiscriminately used by all the vendors to all the peas, and the cry of “Green Hastens!” resounds through every street and alley of London to the very latest crop of the season. Peas become plentiful and cheap in June, and are retailed from carts in the streets at tenpence, eightpence, and sixpence per peck. (Newgate, on the north side of Ludgate Hill is built entirely of stone.)

![Hotloaves]()

Hot loaves, for the breakfast and tea table, are cried at the hours of eight and nine in the morning, and from four to six in the afternoon, during the summer months. These loaves are made of the whitest flour and sold at one and two a penny. In winter, the crier of hot loaves substitutes muffins and crumpets, carrying them in the same manner, and in both instances carrying a little bell as he passes through the streets. (St Martin in the Fields, the design of this portico was taken from an ancient temple at Nismes in France and is particularly grand and beautiful.)

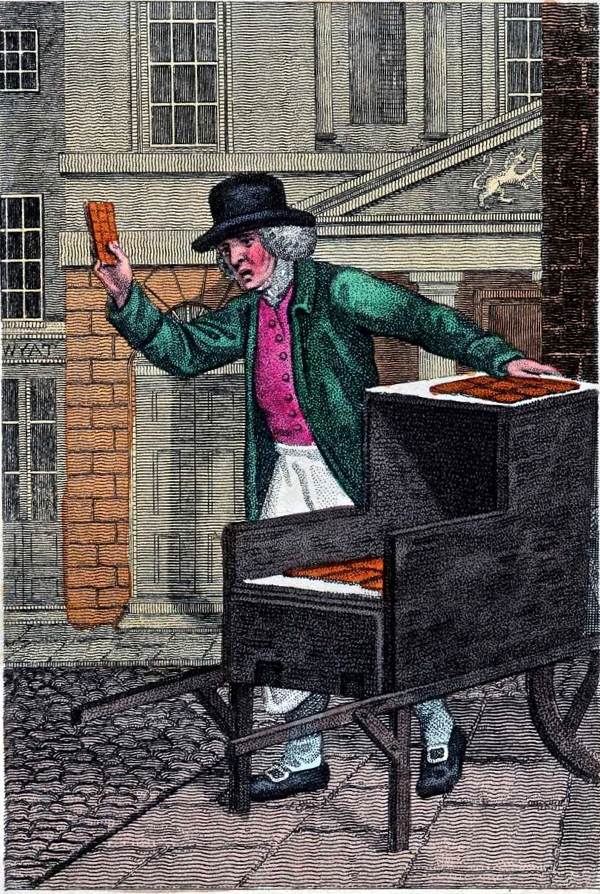

![Hot Spiced Gingerbread]()

Hot Spiced Gingerbread, sold in oblong flat cakes of one halfpenny each, very well made, well baked and kept extremely hot is a very pleasing regale to the pedestrians of London in cold and gloomy evenings. This cheap luxury is only to be obtained in winter, and when that dreary season is supplanted by the long light days of summer, the well-known retailer of Hot Spiced Gingerbread, portrayed in the plate, takes his stand near the portico of the Pantheon, with a basket of Banbury and other cakes. (The Pantheon stands on Oxford St, originally designed for concerts, it is only used for masquerades in the winter season.)

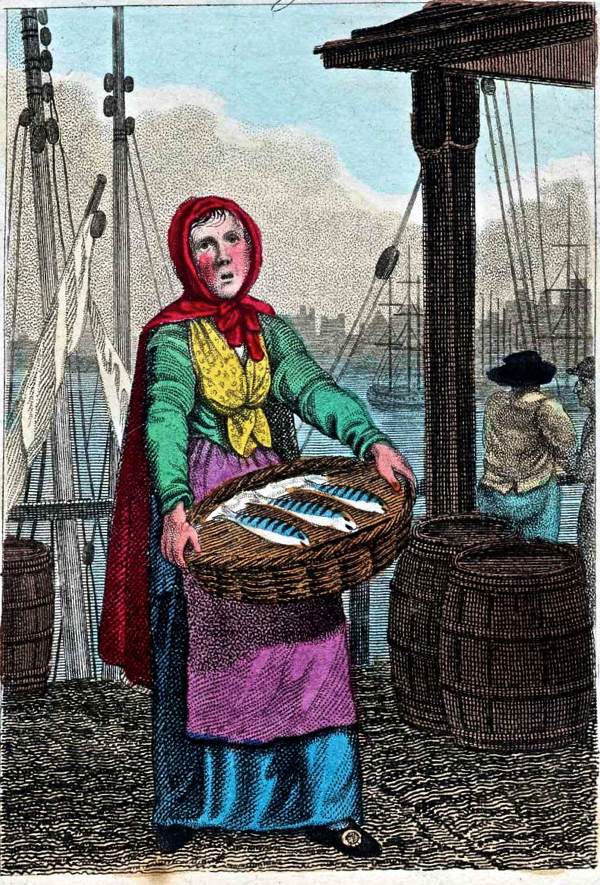

![Mackerel]()

Mackerel – More plentiful than any other fish in London, they are brought from the western coast and afford a livelihood to numbers of men and women who cry them through the streets every day in the week, not excepting Sunday. Mackerel boats being allowed by act of Parliament to dispose of their perishable cargo on Sunday morning, prior to the commencement of divine service. No other fish partake that privilege. (Billingsgate Market commences at three o’clock in the morning in summer and four in winter. Salesmen receive the cargo from the boats and announce by a crier of what kinds they consist. These salesmen have a great commission and generally make fortunes.)

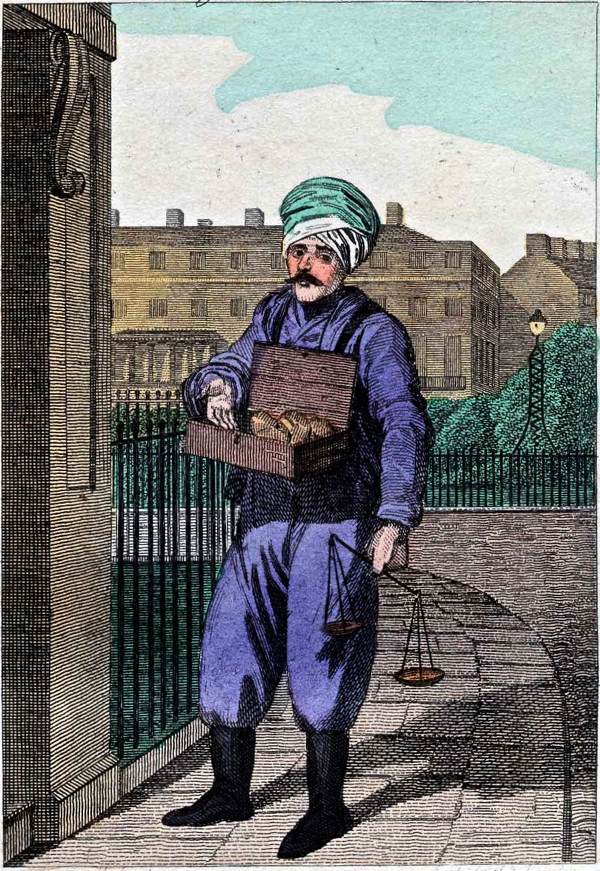

![Rhubarb!]()

Rhubarb! – The Turk, whose portrait is accurately given in this plate, has sold Rhubarb in the streets of the metropolis during many years. He constantly appears in his turban, trousers and mustachios and deals in no other article. As his drug has been found to be of the most genuine quality, the sale affords him a comfortable livelihood. (Russell Sq is one of the largest in London, broad streets intersect at its corners and in the middle, which add to its beauty and remove the general objection to squares by ventilating the air.)

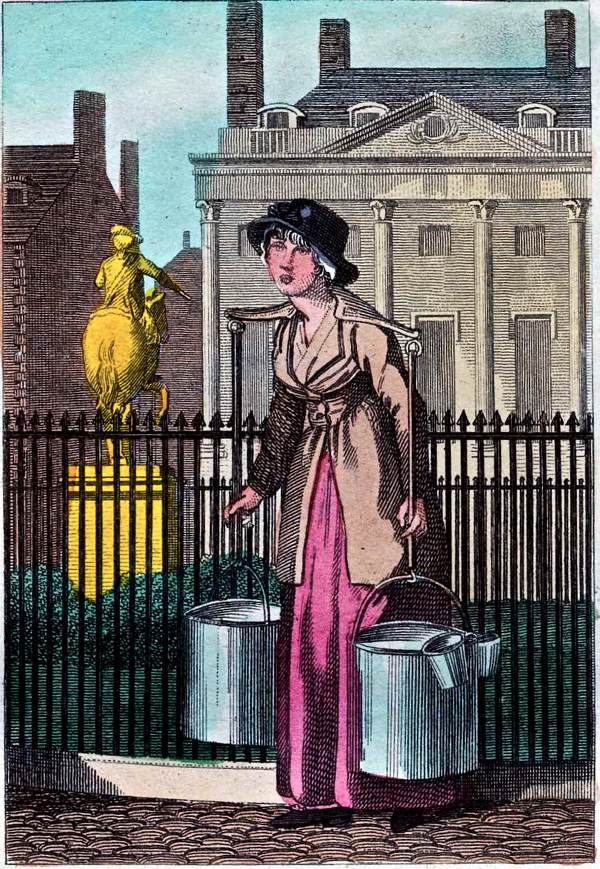

![Milk Below!]()

Milk below! – Every day of the year, both morning and afternoon, milk is carried through each square, each street and alley of the metropolis in tin pails, suspended from a yoke placed on the shoulders of the crier. Milk is sold at fourpence per quart or fivepence for the better sort, yet the advance of price does not ensure its purity for it is generally mixed in a great proportion with water by the retailers before they leave the milk houses. The adulteration of the milk added to the wholesale cost leaves an average profit of cent per cent to the vendors of this useful article. Few retail traders are exercised with equal gain. (Cavendish Sq is in Marylebone. In the centre of the enclosure, erected on a lofty pedestal is a bronze statue of William Duke of Cumberland, all very richly gilded and burnished. In the background are two very elegant houses built by Mr Tufnell.)

![Matches]()

Matches – The criers are very numerous and among the poorest inhabitants, subsisting more on the waste meats they receive from the kitchens where they sell their matches at six bunches per penny, than on the profits arising from their sale. Old women, crippled men, or a mother followed by three or four ragged children, and offering their matches for sale are often relieved when the importunity of the mere beggar is rejected. The elder child of a poor family, like the boy seen in the plate, are frequent traders in matches and generally sing a kind of song, and sell and beg alternately. (The Mansion House is a stone building of considerable magnitude standing at the west end of Cornhill, the residence of the Lord Mayor of London. Lord Burlington sent down an original design worthy of Palladio, but this was rejected and the plan of a freeman of the City adopted in its place. The man was originally a shipwright and the front of his Mansion House has all the resemblance possible to a deep-laden Indiaman.)

![Strawberries]()

Strawberries – Brought fresh gathered to the markets in the height of their season, both morning and afternoon, they are sold in pottles containing something less than a quart each. The crier adds one penny to the price of the strawberries for the pottle which if returned by her customer, she abates. Great numbers of men and women are employed in crying strawberries during their season through the streets of London at sixpence per pottle. ( Covent Garden Market is entirely appropriated to fruit & vegetables. In the south side is a range of shops which contain the choicest produce and the most expensive productions of the hot house. The centre of the market, as shown in the plate, although less pleasing to the eye is more inviting to the general class of buyers.)

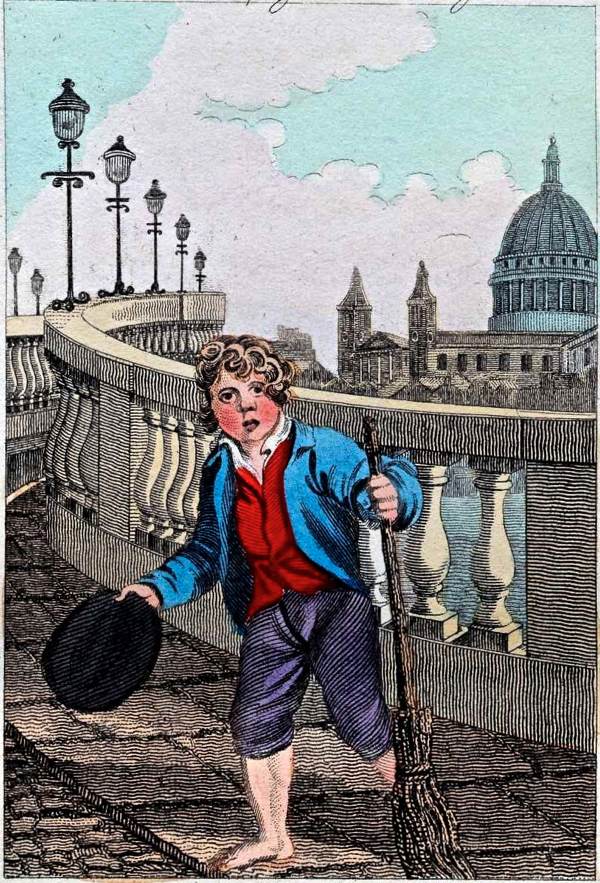

![A Poor Sweep, Sir!]()

A Poor Sweep Sir! – In all the thoroughfares of the metropolis, boys and women employ themselves in dirty weather in sweeping crossings. The foot passenger is constantly importuned and frequently rewards the poor sweep with a halfpenny, which indeed he sometimes deserves for in the winter after fall of snow if a thaw should come before the scavengers have had time to remove it, many streets cannot be crossed without being up to the middle of the leg in dirt. Many of these sweepers who choose their station with judgement reap a plentiful harvest from their labours. (Blackfriars Bridge crosses the river from Bridge St to Surrey St where this view is taken. The width and loftiness of the arches and the whole light construction of this bridge is uncommonly pleasing to the eye and St Paul’s cathedral displays much of the grandeur of its extensive outline when viewed from Blackfriars Bridge.)

![Knives to Grind]()

Knives to grind! – The apparatus of a knife grinder is accurately delineated in this plate. The same wheel turns his grinding and his whetting stone. On a smaller wheel, projecting beyond the other he trundles his commodious shop from street to street. He charges for grinding and setting scissors one penny or twopence per pair, for penknives one penny each and table knives one shilling and sixpence per dozen, according to the polish that is required. (Whitehall – this beautiful structure stands in Parliament St, begun in 1619 from a design by Inigo Jones in his purest manner and cost £17,000. The northern end of the palace, to the left of the plate, is that through which King Charles stepped onto the scaffold.)

![Lavender]()

Lavender – “Six bunches a penny, sweet lavender!” is the cry that invites in the street the purchasers of this cheap and pleasant perfume. A considerable quantity of the shrub is sold to the middling-classes of the inhabitants, who are fond of placing lavender among their linen - the scent of which conquers that of the soap used in washing. (Temple Bar was erected to divide the strand from Fleet St in 1670 after the Great Fire. On the top of this gate were exhibited the heads of the unfortunate victims to the justice of their country for the crime of high treason. The last sad mementos of this kind were the rebels of 1746.)

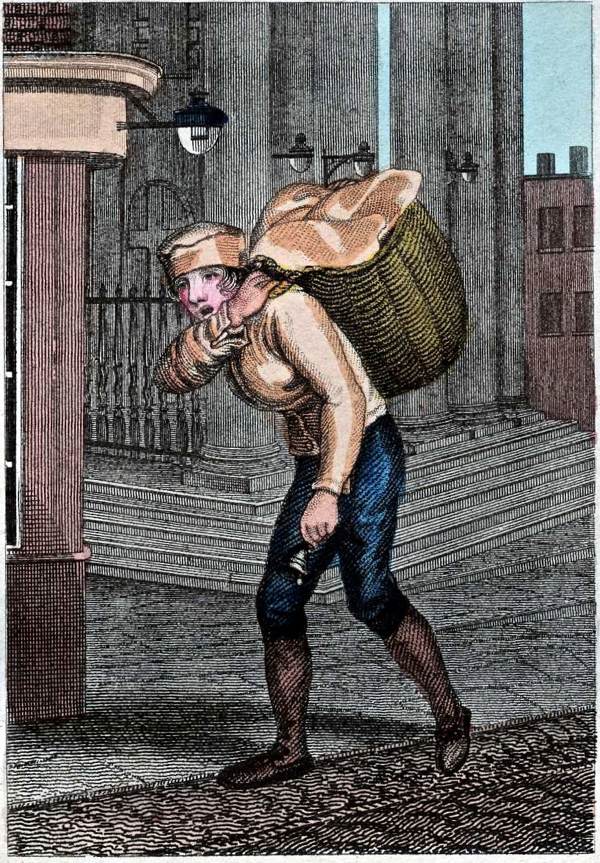

![Sweep Soot O]()

Sweep Soot O! – The occupation of chimney sweep begins with break of day. A master sweep patrols the street for custom attended by two or three boys, the taller ones carrying the bag of soot, and directing the diminutive creature who, stripped perfectly naked, ascends and cleans the chimney. The greatest profit arises from the sake of soot which is used for manure. The hard condition of the sweep devolves upon the smallest and feeblest of the children apprenticed from the parish workhouse. (Foundling Hospital, a handsome and commodious building in Guildford St, stands at the upper end of a large piece of ground in which the children of the foundation are allowed to play in fine weather.)

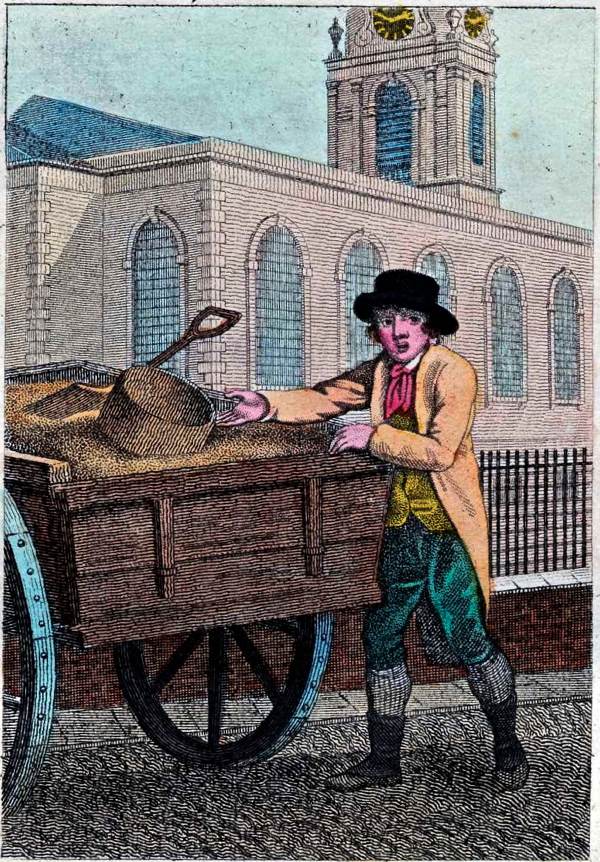

![Sand O!]()

Sand O! – Sand is an article of general use in London, principally for cleaning kitchen utensils. Its greatest consumption is in the outskirts of the metropolis where the cleanly housewife strews sand plentifully over the floor to guard her newly scoured boards from dirty footsteps, a carpet of small expense and easy to be renewed. Sand is sold by measure, red sand twopence halfpenny and white five farthings per peck. (St Giles’ Church at the west end of Broad St Giles is a very handsome structure. Over the gate, entering the church yard is fixed a curious bass-relief representing the Last Judgement and containing a very great number of figures, set up in the 1686)

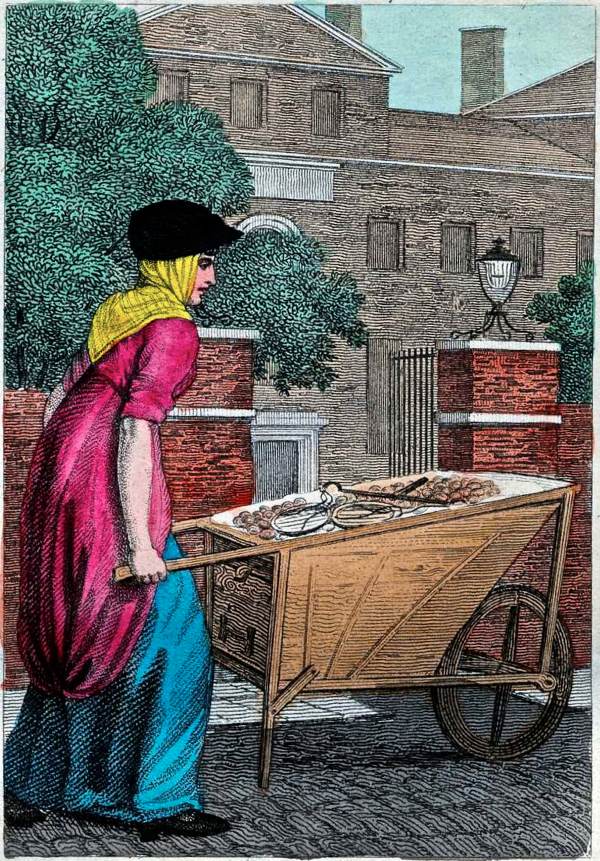

![New Potatoes]()

New potatoes – About the latter end of June and July, they become sufficiently plentiful to be cried at a tolerable rate in the streets. They are sold wholesale in markets by the bushel and retail by the pound. Three halfpence or a penny per pound is the average price from a barrow. (Middlesex Hospital at the northern end of Berners St is the county hospital for diseased persons. It stands in a large court with trees, covered by a wall in front with two gates, one of which is represented in the plate.)

![Water Cresses]()

Water Cresses – The crier of water cresses frequently travels seven or eight miles before the hour of breakfast to gather them fresh. There is a good supply in the Covent Garden Market brought along with other vegetables where they are cultivated like other garden stuff, but they are inferior to those grown in the natural state in a running brook, wanting that pungency of taste which makes them very wholesome. (Hanover Sq is on the south side of Oxford St, there is a circular enclosure in the middle with a plain grass plot. In George St, leading into the square, is the curious and extensive anatomical museum of Mr Heaviside the surgeon, to the inspection of which respectable persons are admitted, on application to Mr Heaviside, once a week.)

![Slippers]()

Slippers – The Turk is a portrait, habited in the costume of his nation, he has sold Morocco Slippers in the Strand, Cheapside and Cornhill, a great number of years. To these principal streets, he generally confines his walks. There are other sellers of slippers, particularly about the Royal Exchange who are very importunate for custom while the venerable Turk uses no solicitation beyond showing his slippers. They are sold at one shilling and sixpence per pair and are of all colours. (Somerset House is a noble structure built by the government for the offices of public business. The plate shows the west side of the entrance which contains a gate for carriages and two foot ways. A visit will amply repay the trouble of a stranger.)

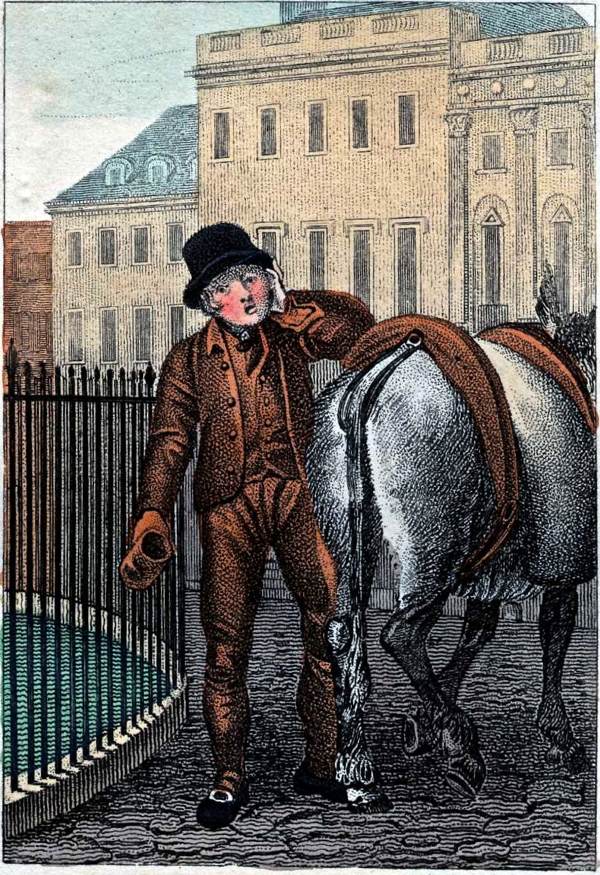

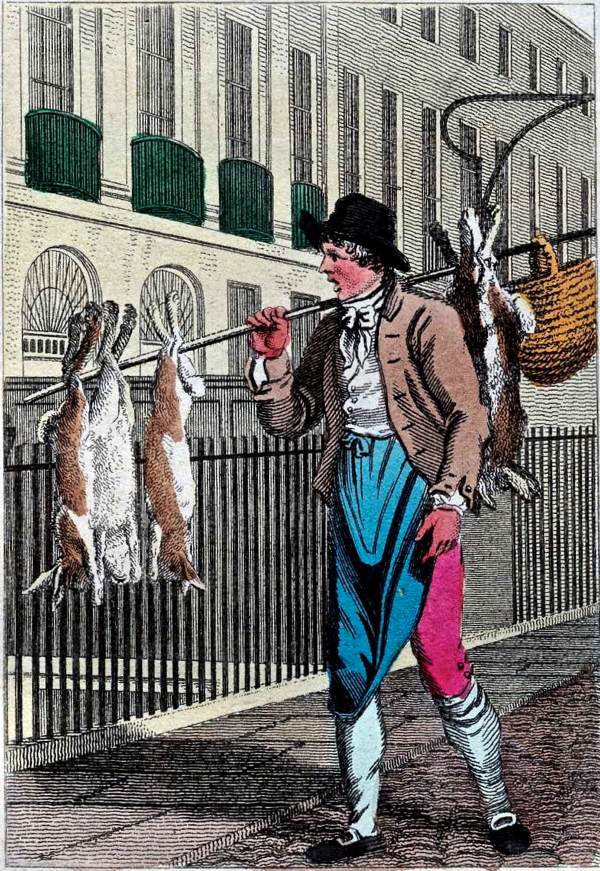

![Rabbits]()

Rabbits – The crier of rabbits in the plate is a portrait well known by persons who frequent the streets at the west end of town. Wild and tame rabbits are sold from ninepence to eighteen pence each, which is cheaper than they can be bought in the poulterers’ shops. (Portland Place is an elegant street to the north of Marylebone. From the opening at the upper end is a fine view of Harrow and the Hampstead and Highgate Hills, making it one of the airiest situations in town. The houses being of perfect uniformity and no shops or meaner buildings interrupting the regularity of the design, it is one of the finest street in London.)

Images courtesy Bishopsgate Institute

You may like to explore these other sets of Cries of London

John Player’s Cries of London

More John Player’s Cries of London

Faulkner’s Street Cries

Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

More Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London

Kendrew’s Cries of London

London Characters

Geoffrey Fletcher’s Pavement Pounders

William Craig Marshall’s Itinerant Traders

London Melodies

Henry Mayhew’s Street Traders

H.W.Petherick’s London Characters

John Thomson’s Street Life in London

Aunt Busy Bee’s New London Cries

William Nicholson’s London Types

John Leighton’s London Cries

Francis Wheatley’s Cries of London

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana of 1817

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana II

John Thomas Smith’s Vagabondiana III

Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

More of Thomas Rowlandson’s Lower Orders

Victorian Tradesmen Scraps

Cries of London Scraps

New Cries of London 1803

Cries of London Snap Cards

Julius M Price’s London Types

![Demolition Image[1]](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Demolition-Image14-600x417.jpg)

.

.