![10565282_10152364061613541_7834627965490097766_n]()

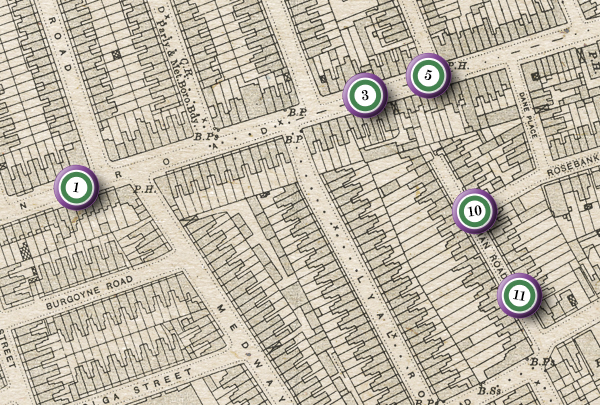

On the day of the opening of Sarah Gavron’s film SUFFRAGETTE which dramatises the contribution of women in the East End to the Suffrage Movement, we present Researcher Vicky Stewart & Designer Adam Tuck‘s map of some key events in the struggle in Bethnal Green, Roman Rd & Bow

![suffragetteMap01zoomBoxes2000withNos]()

Click to enlarge and see the map in the detail

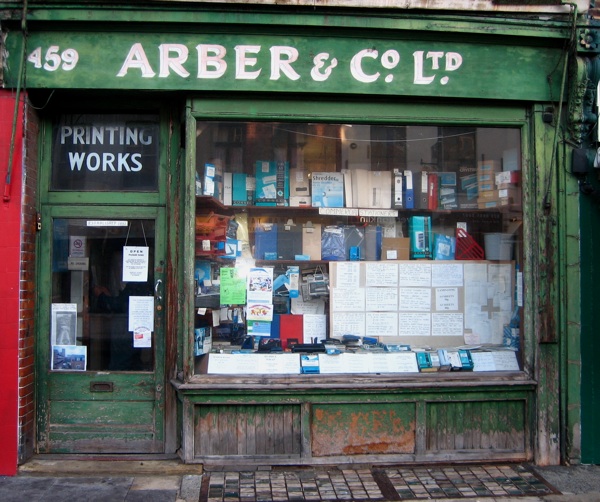

The closure of W F Arber & Co Ltd, after one hundred and seventeen years in the Roman Rd, inspired me to look further at Gary Arber’s story of his grandmother, Emily Arber, organising the free printing of handbills and posters for the Suffragette movement. Just what was going on locally, who were involved, and how were these Suffragettes organised?

Nothing prepared me for what I discovered. My knowledge of Suffragette activity was limited to stories of upper middle class ladies marching behind Mrs Pankhurst, waving ‘Votes for Women’ banners, being imprisoned, getting force-fed, and then eventually securing the vote. In part this was true – Mrs Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel believed middle class women had the education and influence to bring about the necessary change, but Sylvia disagreed and insisted it was only direct action by working class women that could win the vote.

In 1912, Sylvia Pankhurst came to Bow as representative of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) to campaign for local MP George Lansbury, who had resigned his seat in parliament to fight a by-election on the issue of votes for women. Although Lansbury lost the election, he continued to support Sylvia who decided to stay in the East End and do everything in her power to carry on the fight – not only to champion the cause of Suffrage but also to challenge injustice and alleviate suffering wherever she could.

She opened her first WSPU Headquarters in Bow Rd in 1912 but moved to Roman Rd when forming the East London Federation, whose policy was to “combine large-scale public demonstrations with public militancy… [to attract] immediate arrest.”

In January 1914, Christabel asked Sylvia to change the name of the ELF and separate from the WSPU, and the organisation became the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS) with new headquarters in Old Ford Rd.

What amazes me about this story is the number of women – often with active support of husbands or sons – who, despite harsh poverty and large families, gave huge support to Sylvia and the campaign. They risked assault and often were beaten by policemen at rallies, on marches and at meetings. They risked being sent to Holloway and subjected to force-feeding. They risked the anger and abuse of those who did not support Women’s’ Suffrage.

So who were these women and what do we know of them? Below you can read extracts from Sylvia Pankhurst’s books, ‘The Suffragette Movement’ and ‘The Home Front’, which locate their actions in the East End.

- Vicky Stewart

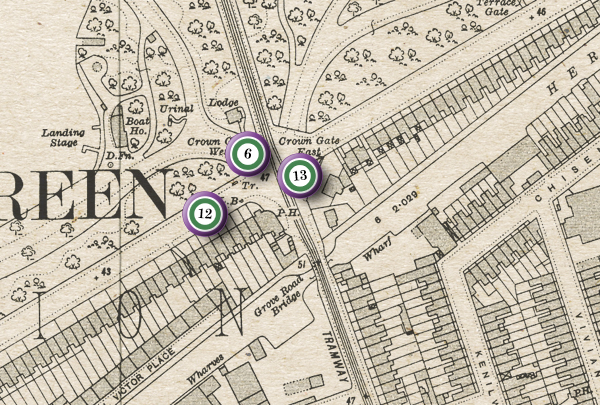

![suffragetteMap01zoom01]()

6

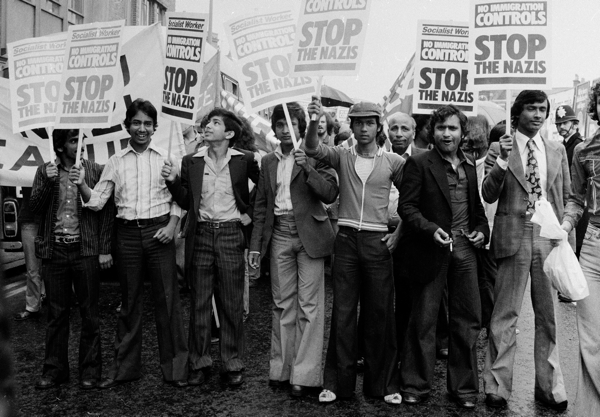

Victoria Park “On Sunday, May 25th 1913, was held ‘Women’s May Day’ in East London. The Members of Bow, Bromley, Poplar, and neighbouring districts had prepared for it for many weeks past and had made hundreds of almond branches, which were carried in a great procession with purple, white and green flags, and caps of Liberty flaunting above them from the East India Dock gates by winding ways, to Victoria Park. A vast crowd of people – the biggest ever seen in East London – assembled ….. to hear the speakers from twenty platforms.”

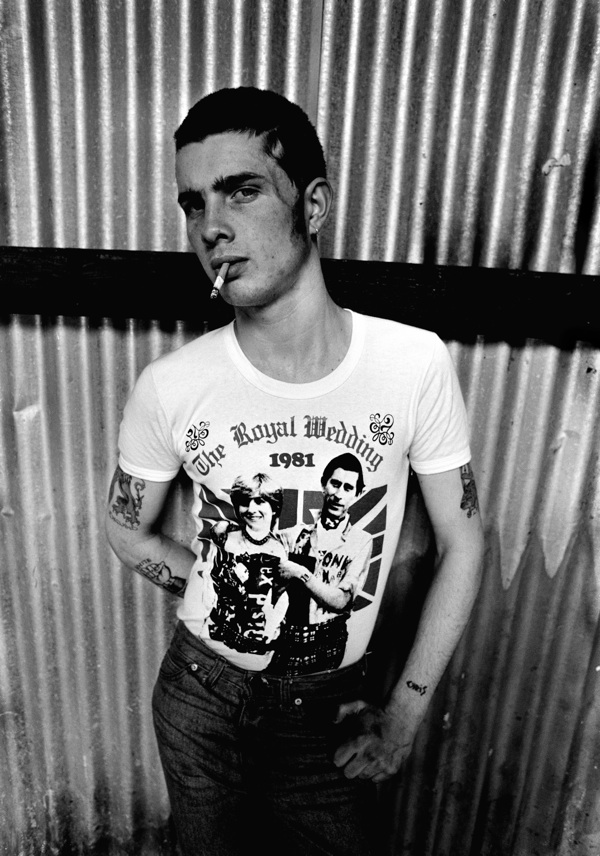

![img082 - Version 2]()

12

288 Old Ford Rd was home to Israel Zangwill, political activist and strong supporter of Sylvia and the Suffragette movement.

13

304 Old Ford Rd was home to Mrs Fischer where meetings were held .

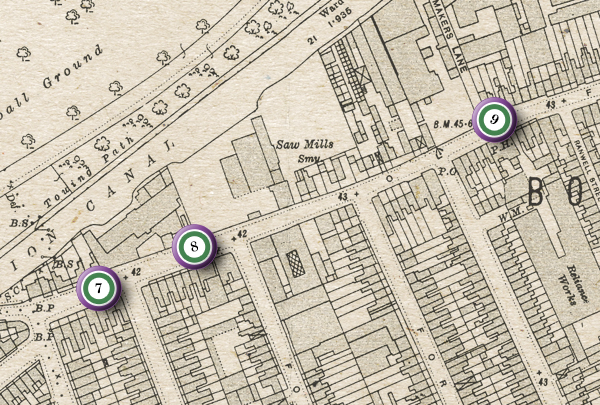

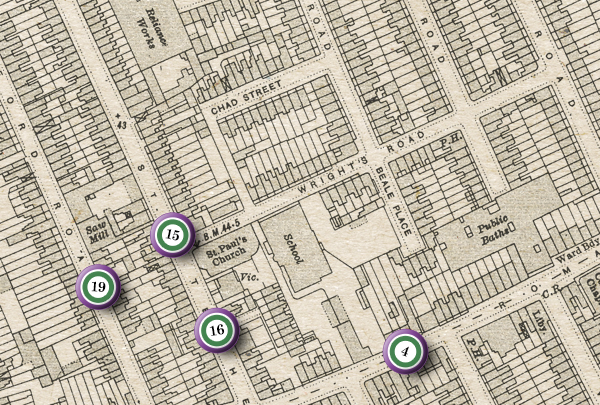

![suffragetteMap01zoom02]()

7

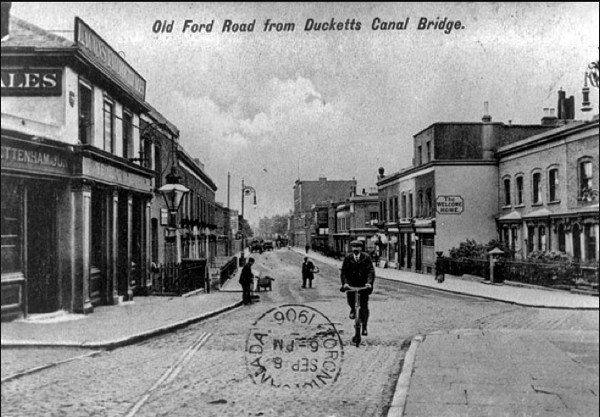

Old Ford Rd was the route taken by the Suffragettes May Day processions to Victoria Park when they met with violence from the police at the gates and suffered many injuries.

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

8

400 Old Ford Rd became the third headquarters of the East London Federation of Suffragettes in 1914. A Women’s Hall was built on land behind which was used for a cost-price restaurant which provided nutritious meals for a pittance to women suffering from the huge rise in food prices in the early months of the war.

9

438 Old Ford Rd, The Mother’s Arms The ELFS set up another creche and baby clinic on this street, staffed by trained nurses and developed upon Montessori lines. This was housed in a converted pub called The Gunmaker’s Arms, whose name was changed to The Mother’s Arms.

![Old Ford Rd]()

![suffragetteMap01zoom03]()

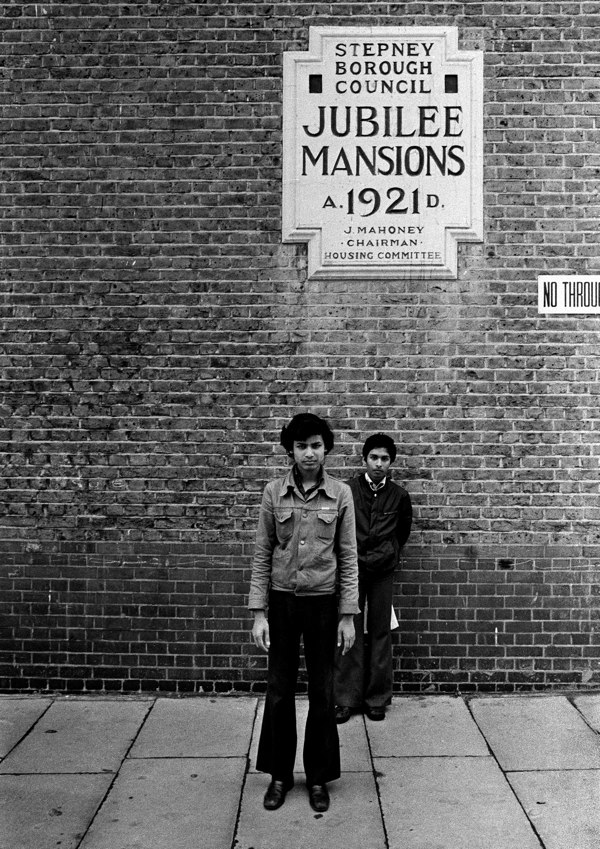

1

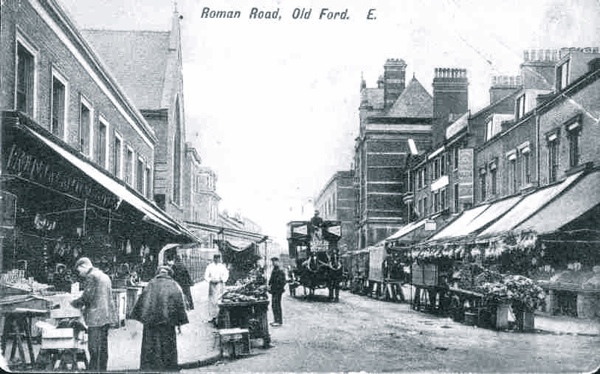

Roman Rd “I decided to take the risk of opening a permanent East End headquarters in Bow … Miss Emerson and I went down there together one frosty Friday morning in February to hunt for an office. The sun was like a red ball in the misty, whitey-grey sky. Market stalls, covered with cheerful pink and yellow rhubarb, cabbages, oranges and all sorts of other interesting things, lined both sides of the narrow Roman Rd. ‘The Roman’ , as they call it, was crowded with busy kindly people. I had always liked Bow. That morning my heart warmed to it for ever.”

![Roman1]()

3

159 Roman Rd, (now 459) Arber & Co Ltd, Printing Works where Suffragette handbills were printed under the supervision of Emily Arber.

![img_0199]()

5

152 Roman Rd In 1912, tickets were available from this house, home of Mrs Margaret Mitchell, second-hand clothes dealer, for a demonstration in Bow Palace with Mrs Pankhurst and George Lansbury.

10 & 11

45 Norman Rd (now Norman Grove) A toy factory was opened in October 1914 to provide women with an income whilst their husbands were at War. They were paid a living wage and could put their children into the nursery further down the road.

![suffragetteMap01zoom04]()

4

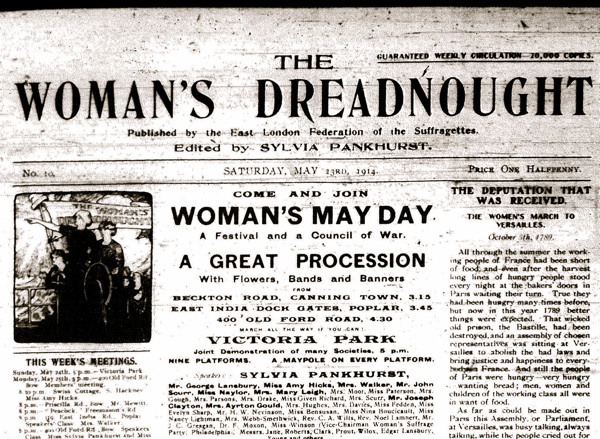

Roman Rd Market The East London Federation of Suffragettes ran a stall in the market, decorated with posters and selling their newspaper, The Women’s Dreadnought – a “medium through which working women, however unlettered, might express themselves and find their interests defended.”

![Roman2]()

15

103 St Stephen’s Rd was home to George Lansbury and his family.

16

St Stephen’s Rd “On November 5th 1913, on my way to a Meeting to inaugurate the People’s Army, I happened to call at Mr Lansbury’s house in St Stephen’s Rd. The house was immediately surrounded by detectives and policemen and there seemed no possibility of mistake. But the people of Bow, on hearing of the trouble, came flocking out of the Baths where they had assembled. In the confusion that ensued the detectives dragged Miss Daisy Lansbury off in a taxi, and I went free.

When the police authorities realised their mistake, and learnt that I was actually speaking at the Baths, they sent hundreds of men to take me, but though they met the people in the Roman Rd as they came from the Meeting I escaped. Miss Emerson was again struck on the head, this time by a uniformed constable, and fell to the ground unconscious. Many other people were badly hurt. The people replied with spirit. Two mounted policemen were unhorsed and many others were disabled.”

![Bow Baths 3]()

19

28 Ford Rd “The members had begged me, if ever I should be imprisoned under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’, to come down to them in the East End, in order that they might protect me, they would not let me be taken back to prison without a struggle as the others had been, they assured me.

On the night of my arrest Zelie Emerson had pressed into my hand an address: ‘Mr and Mrs Payne, 28 Ford Rd, Bow.’ Thither I was now driven in a taxi with two wardresses. As the cab slowed down perforce among the marketing throngs in the Roman Road, friends recognised me, and rushed to the roadway, cheering and waving their hands. Mrs Payne was waiting for me on the doorstep. It was a typical little East End house in a typical little street, the front door opening directly from the pavement, with not an inch of ground to withdraw its windows from the passers-by. I was welcomed by the kindest of kind people, shoemaking home-workers, who carried me in with the utmost tenderness.

They had put their double bed for me in the little front parlour on the ground floor next the street, and had tied up the door knocker. For three days they stopped their work that I might not be disturbed by the noise of their tools. Yet there was no quiet. The detectives, notified of my release, had arrived before me. A hostile crowd collected. A woman flung one of the clogs she wore at the wash-tub at a detectives head. The ‘Cats’, as a hundred angry voices called them, retired to the nearby public-houses, there were several of these havens within a stone’s throw, as there usually are in the East End.

Yet, even though the detectives were out of sight, people were constantly stopping before the house to discuss the Movement and my imprisonment. Children gathered, with prattling treble. If anyone called at the house, or a vehicle stopped before it, detectives at once came hastening forth, a storm of hostile voices. Here indeed was no peace. My hosts carried me upstairs to their own bedroom, at the back of the house, hastily prepared, a small room, longer but scarcely wider than a prison cell – my home when out of prison for many months to come. (…)

In that little room I slept, wrote, interviewed the Press and personalities of all sorts, and presently edited a weekly paper. Its walls were covered with a cheap, drab paper, with an etching of a ship in full sail, and two old fashioned colour prints of a little girl at her morning and evening prayers. From the window by my bed, I could see the steeple of St Stephen’s Church and the belfry of its school, a jumble of red-tiled roofs, darkened by smoke and age, the dull brick of the walls and the new whitewash of some of the backyards in the next street.

Our colours were nailed to the wall behind my bed, and a flag of purple, white and green was displayed from an opposite dwelling, where pots of scarlet geraniums hung on the whitewashed wall of the yard below, and a beautiful girl with smooth, dark hair and a white bodice would come out to delight my eyes in helping her mother at the wash-tub. The next yard was a fish curers’. An old lady with a chenille net on her grey hair would be passing in and out of the smoke-house, preparing the sawdust fires. A man with his shirt sleeves rolled up would be splitting herrings, and another hooking them on to rods balanced on boards and packing-cases, till the yard was filled, and gleamed with them like a coat of mail. Close by, tall sunflowers were growing, and garments of many colours hung out to dry. Next door to us they bred pigeons and cocks and hens, which cooed and crowed and clucked in the early hours. Two doors away a woman supported a paralysed husband and a number of young children by making shirts at 8d a dozen. Opposite, on the other side of Ford St, was a poor widow with a family of little ones. The detectives endeavoured to hire a room from her, that they might watch me unobserved. “It will be a small fortune to you while it lasts!” they told her. Bravely she refused with disdain, “Money wouldn’t do me any good if I was to hurt that young woman!” The same proposal was made and rejected at every house in Ford Rd.

Flowers and presents of all kinds were showered on me by kindly neighbours. One woman wrote to say that she did not see why I should ever go back to prison when every woman could buy a rolling pin for a penny.”

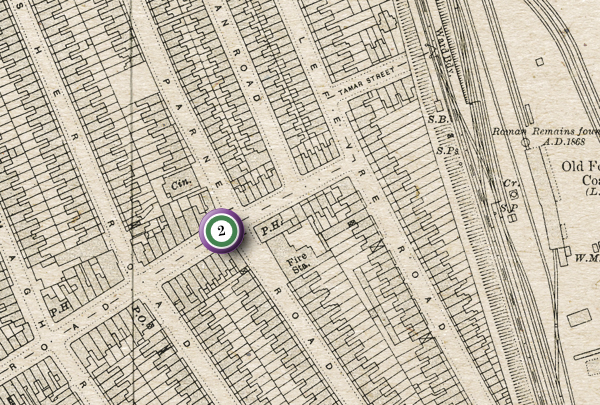

![suffragetteMap01zoom05]()

2

321 Roman Rd, Second Headquarters of the East London Federation “We decided to take a shop and house at 321 Roman Rd at a weekly rental of 14s 6d a week. It was the only shop to let in the road. The shop window was broken right across, and was only held together by putty. The landlord would not put in new glass, nor would he repair the many holes in the shop and passage flooring because he thought we would only stay a short time. But all such things have since been done.

Plenty of friends at once rallied round us. Women …. came in and scrubbed the floors and cleaned the windows. Mrs Wise, who kept the sweetshop next door, lent us a trestle table for a counter and helped us to put up purple, white and green flags. Her little boy took down the shutters for us every morning, and put them up each night, and her little girls often came in to sweep.”

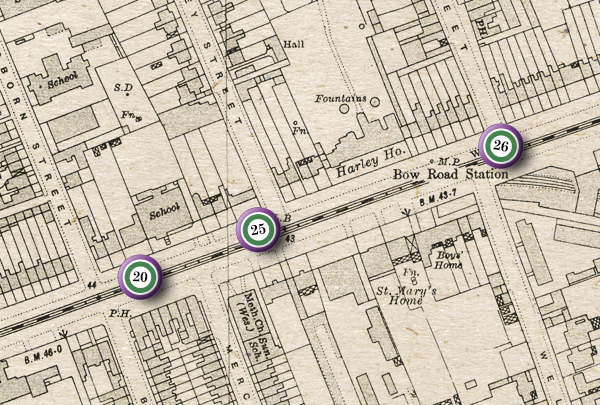

![suffragetteMap01zoom06]()

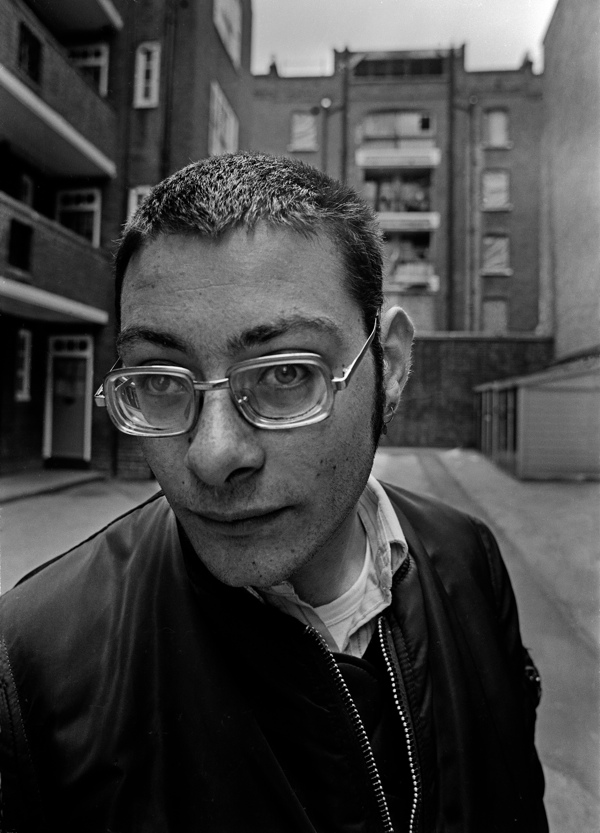

20

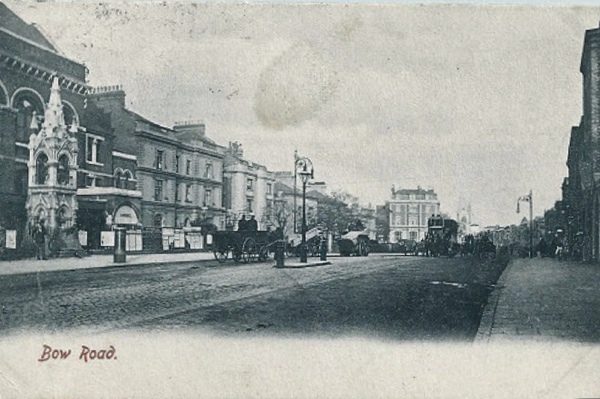

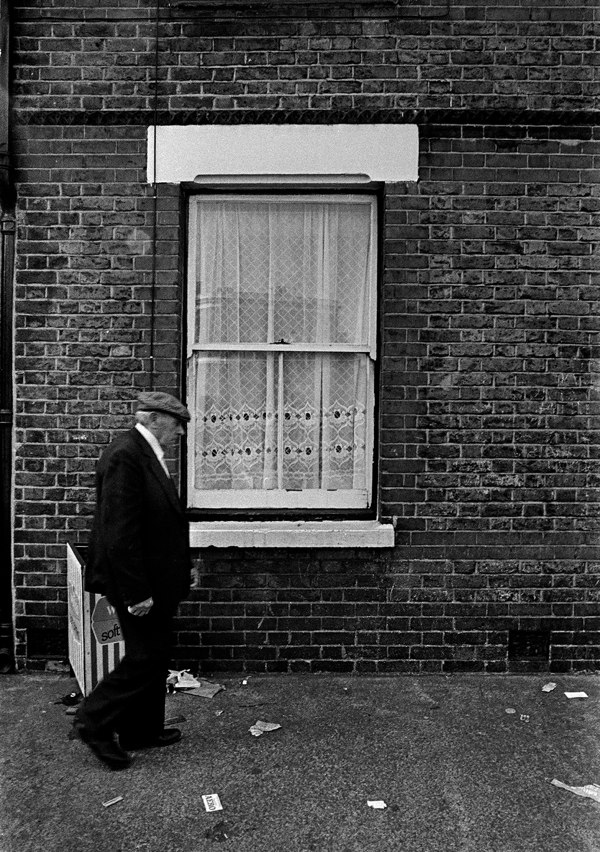

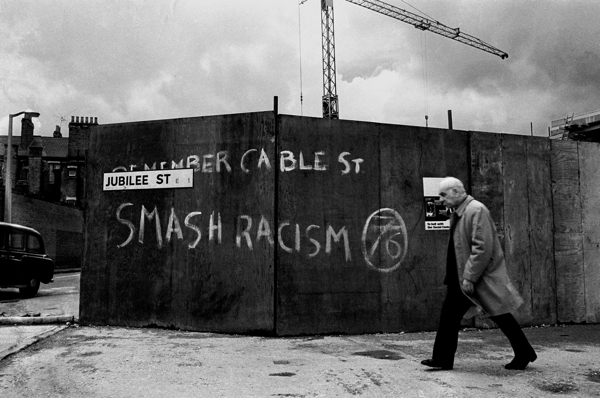

Bow Rd – Sylvia described it as ‘dingy Bow Rd.’

![Bow Rd Again]()

25

The George Lansbury Memorial – Elected to parliament in 1910, he resigned his seat in 1912 to campaign for women’s suffrage, and was briefly imprisoned after publicly supporting militant action.

![lansbury]()

George Lansbury

![IMG_1274]()

26

The Minnie Lansbury Clock is at the Bow Rd near the junction with Alfred St. Minnie Lansbury was the daughter-in-law of George Lansbury, and very actively supported the campaign and was in Holloway. She died at the age of thirty-two.

![IMG_1114]()

![minnie Lansbury on her way to arrest 1921]()

Minnie Lansbury is congratulated on her way to be arrested at Poplar Town Hall

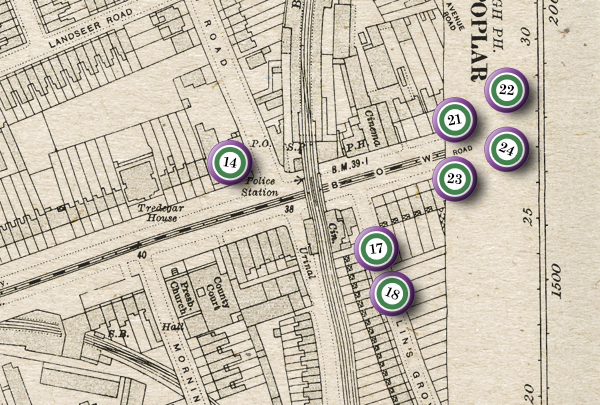

![suffragetteMap01zoom07]()

14

Bow Rd Police Station The police were horrifyingly brutal towards Suffragettes when on demonstrations and then, once arrested and tried, they would often receive excessively harsh prison sentences. Hunger striking was in protest against the government’s failure to treat them as political prisoners.

Mrs Parsons told Asquith - “We do protest when we go along in processions that suddenly without a word of warning we are pounced upon by detectives and bludgeoned and women are called names by cowardly detectives, when nobody is about. There was one old lady of seventy who was with us the other day, who was knocked to the ground and kicked. She is a shirtmaker and is forced to work on a machine and she has been in the most awful agony. These men are not fit to help rule the country while we have no say in the matter.” (From the Woman’s Dreadnought.)

Under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ hunger strikers were released when their lives was in danger so as to recuperate before returning to finish their sentences. They told tales of dreadful brutality during force-feeding in Holloway.

![Bow Police Station]()

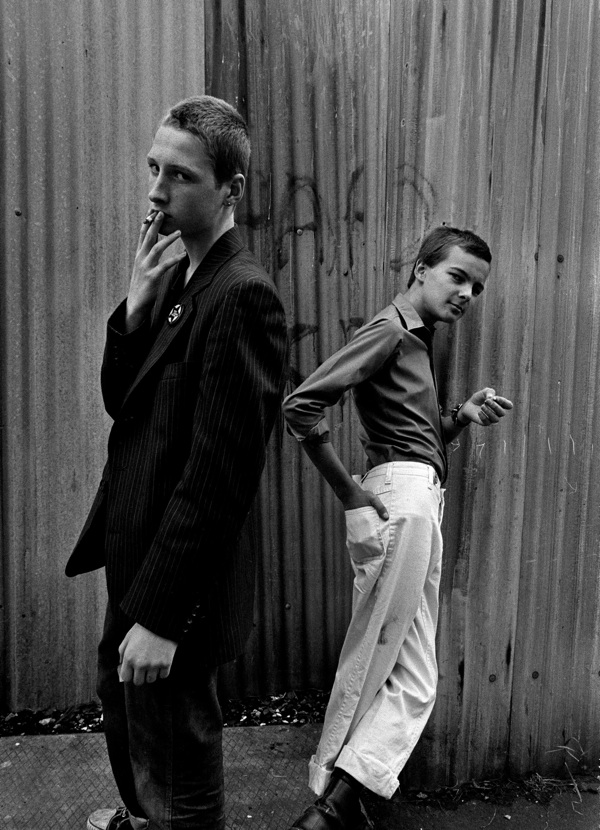

17 & 18

13 Tomlin’s Grove “When the procession turned out of Bow Rd into Tomlin’s Grove they found that the street lamps were not lighted and that a strong force of police were waiting in the dark before the house of Councillor Le Manquais. Just as the people at the head of the procession reached the house, the policemen closed around them and arrested Miss Emerson, Miss Godfrey and seven men, two of whom were not in the procession, but were going home to tea in the opposite direction.

At the same moment twenty mounted police came riding down upon the people from the far end of Tomlin’s Grove, and twenty more from the Bow Rd. The people were all unarmed. … There were cries and shrieks and people ran panic-stricken into the little front gardens of the houses in the Grove.

But wherever the people stopped the police hunted them away. I was told that an old woman who saw the police beating the people in her garden was so much upset that she fell down in a fit and died without regaining consciousness. A boy of eighteen was so brutally kicked and trampled on that he had to be carried to the infirmary for treatment. A publican who was passing was knocked down and kicked and one of his ribs was broken. Even the bandsmen were not spared. The police threw their instruments over the garden walls. The big drummer was knocked down and so badly used that he is still on the list for sick insurance benefit. Mr Atkinson, a labourer, was severely handled and was then arrested. In the charge room Inspector Potter was said to have blacked his eye.”

21

198 Bow Rd was the first Headquarters of the First Headquarters of the East London Federation, 1912. When Sylvia first arrived in Bow she rented an empty baker’s shop at 198 Bow Rd. She used a platform to paint “VOTES FOR WOMEN” in gold across the frontage and addressed the crowds from here.

22

The Obelisk, Bromley High St “On the following Monday, February 17th (1913) we held a meeting at the Obelisk, a mean-looking monument in a dreary, almost unlighted open space near Bow Church.

Our platform, a high, uncovered cart, was pitched against the dark wall of a dismal council school in the teeth of a bitter wind. Already a little knot of people had gathered; women holding their dark garments closely about them, shivering and talking of the cold, four or five police constables and a couple of Inspectors. We climbed into the cart and watched the crowd growing, the men and women turning from the footpaths to join the mass. … I said I knew it to be a hard thing for men and women to risk imprisonment in such a neighbourhood, where most of them were labouring under the steepest economic pressure, yet I pleaded for some of the women of Bow to join us in showing themselves prepared to make a sacrifice to secure enfranchisement …

… After it was over Mrs Watkins, Mrs Moore, Miss Annie Lansbury, and I broke an undertaker’s window. Willie Lansbury, George Lansbury’s eldest son, who had promised his wife to go to prison instead of her because she had tubercular tendencies and could not leave their little daughter only two years old, broke a window in the Bromley Public Hall.

I was seized by two policemen, three other women were seized. We were dragged, resisting, along the Bow Rd, the crowd cheering and running with us. We were sent to prison without an option of fine.

There were four others inside with me: Annie Lansbury and her brother Will, pale, delicate Mrs. Watkins, a widow struggling to maintain herself by sweated sewing-machine work, and young Mrs. Moore. A moment later little Zelie Emerson was bundled in, flushed and triumphant – she had broken the window of the Liberal Club.

That was the beginning of Militancy in East London. Miss Emerson, Mrs Watkins and I decided to do the hunger-strike, and hoped that we should soon be out to work again. But although Mrs Watkins was released after ten days, Miss Emerson and I were forcibly fed, and she was kept in for seven weeks although she had developed appendicitis, and I for five. When we were once free we found that we were too ill to do anything at all for some weeks.

But we need not have feared that the work would slacken without us. A tremendous flame of enthusiasm had burst forth in the East End. Great meetings were held, and during our imprisonment long processions marched eight times the six miles to cheer us in Holloway, and several times also to Brixton goal, where Mr Will Lansbury was imprisoned. The people of East London, with Miss Dalgleish to help them, certainly kept the purple, white and green flag flying …”

![10499839]()

23

Bromley Public Hall, Bow Rd “On February 14th [1913] … we held a meeting in the Bromley Public Hall, Bow Road, and from it led a procession round the district. …To make sure of imprisonment, I broke a window in the police station … Daisy Lansbury was accused of catching a policeman by the belt, but the charge was dismissed. Zelie Emerson and I went to prison … .and began the hunger and thirst strike … On release we rushed back to the shop, found Mrs Lake scrubbing the table, and it crowded with members arranging to march to Holloway Prison to cheer us next day.”

![IMG_1235]()

24

Bow Palace, 156 Bow Rd was built at the rear of the Three Cups public house and had a capacity of two thousand.

“One Sunday afternoon I spoke in Bow Palace and marched openly with the people of Bow Rd. When I spoke from the window afterwards, a veritable forest of sticks was waved by the crowd. …

While I was in prison after my arrest in Shoreditch …. a Meeting …. was held in Bow Palace on Sunday afternoon, December 14th. After the Meeting it was arranged to go in procession around the district and to hoot outside the houses of hostile Borough Councillors.”

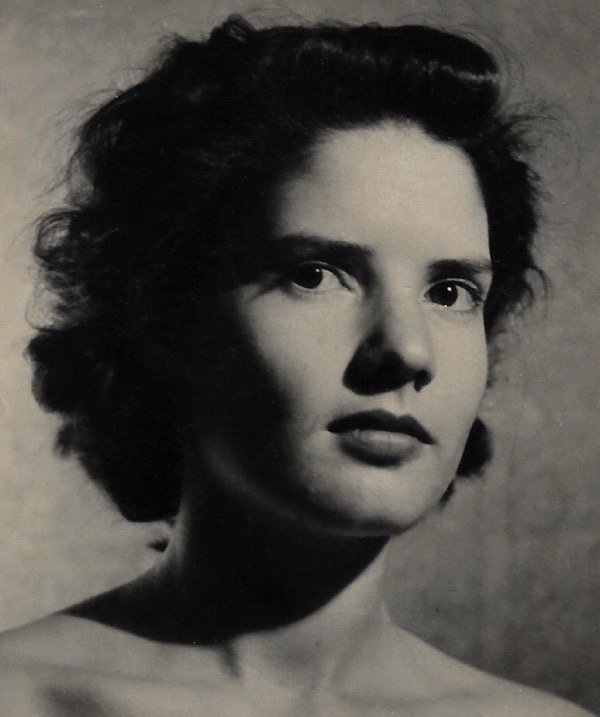

![wf1907 pankhurst]()

Sylvia Pankhurst – Women over the age of twenty-one were eventually enfranchised in 1928

[There is a video that cannot be displayed in this feed. Visit the blog entry to see the video.]

Maps reproduced courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute

Postcard reproduced courtesy of Libby Hall Collection at Bishopsgate Institute

Photograph of Suffragette in Holloway courtesy of LSE Women’s Library

Copy of The Women’s Dreadnought courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives

You may also like to read about

Last Days at W F Arber & Co Ltd

Kate Parry Frye’s Suffrage Diary

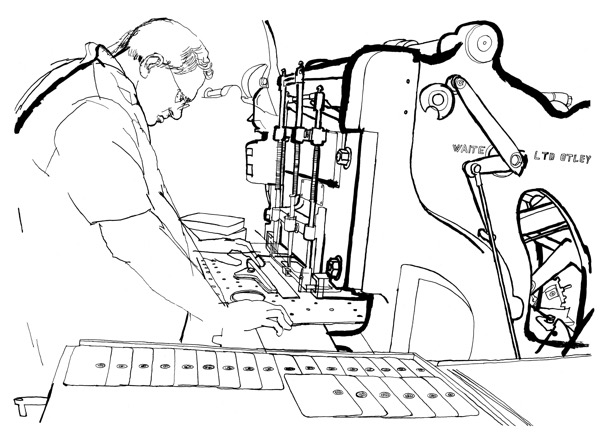

Gita Patel & Wendy Arundel and-folding & glueing envelopes

Gita Patel & Wendy Arundel and-folding & glueing envelopes

Working a manual die-stamping machine

Working a manual die-stamping machine

Jon Webster die-stamping a crest

Jon Webster die-stamping a crest

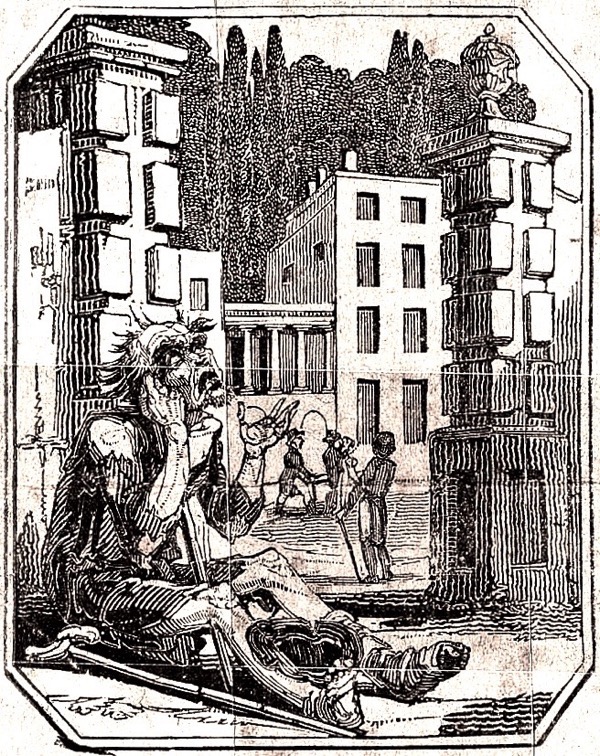

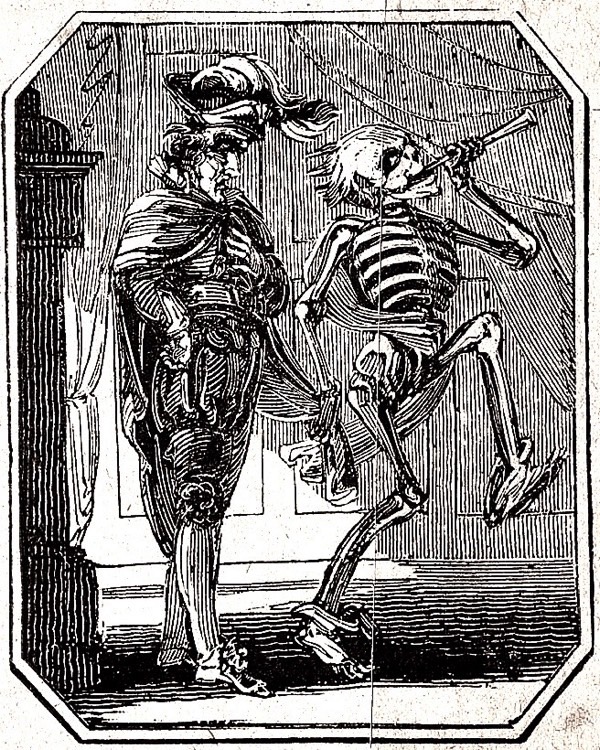

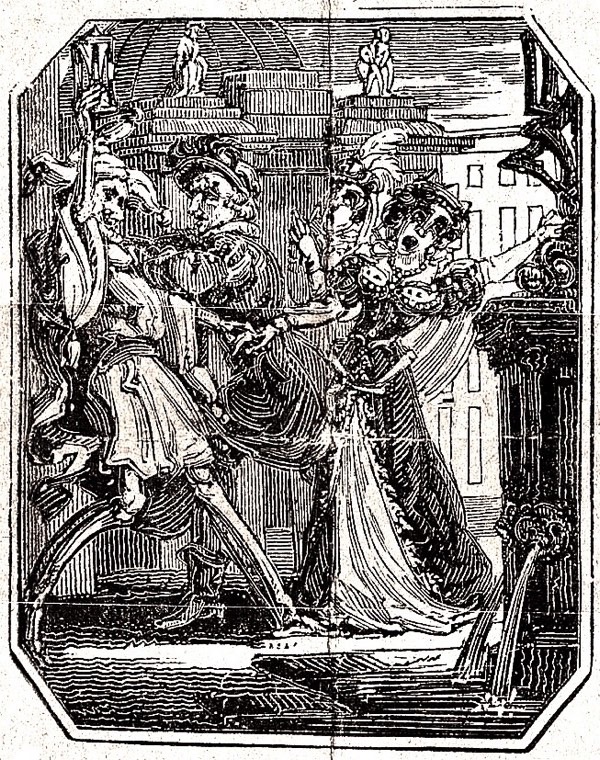

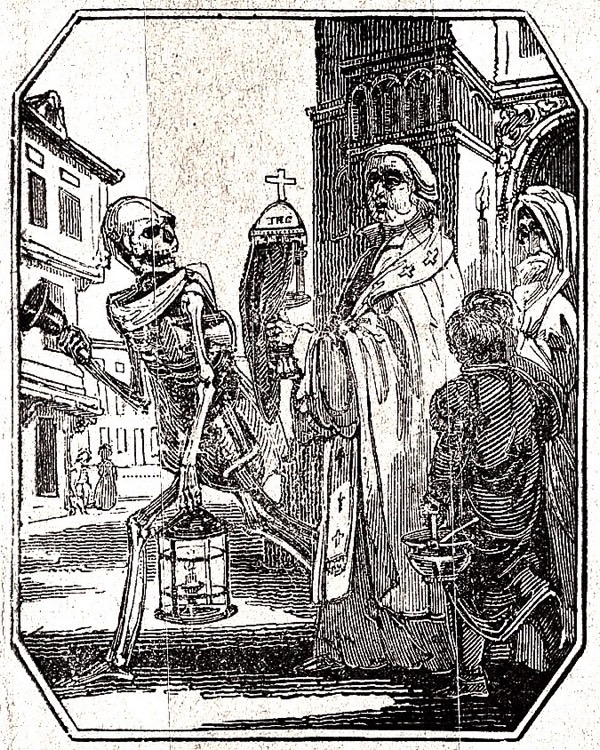

The Pope

The Pope

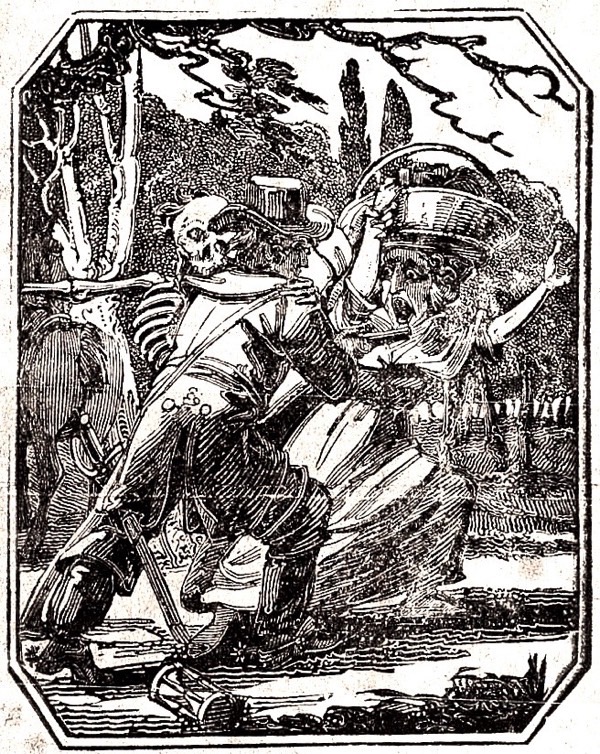

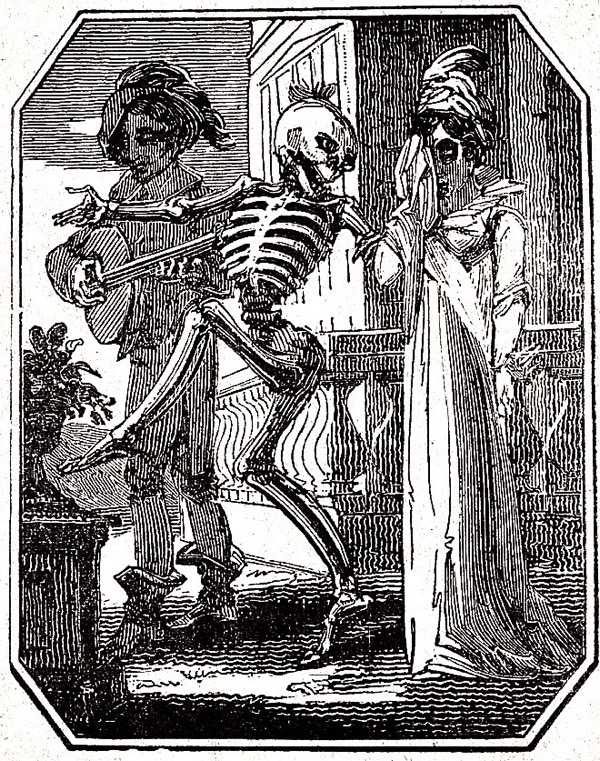

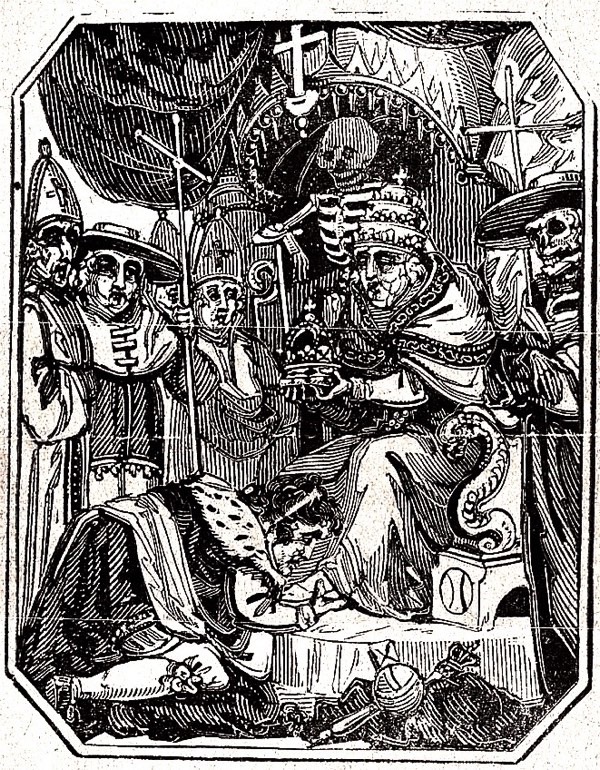

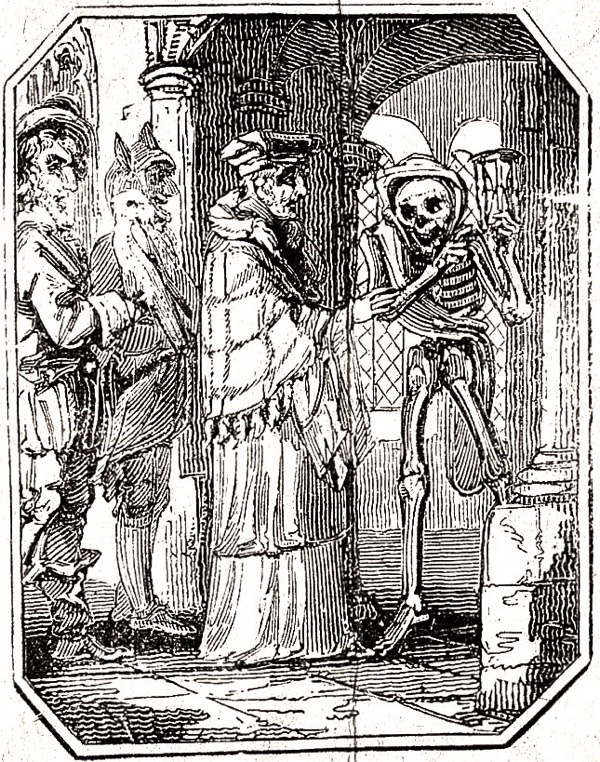

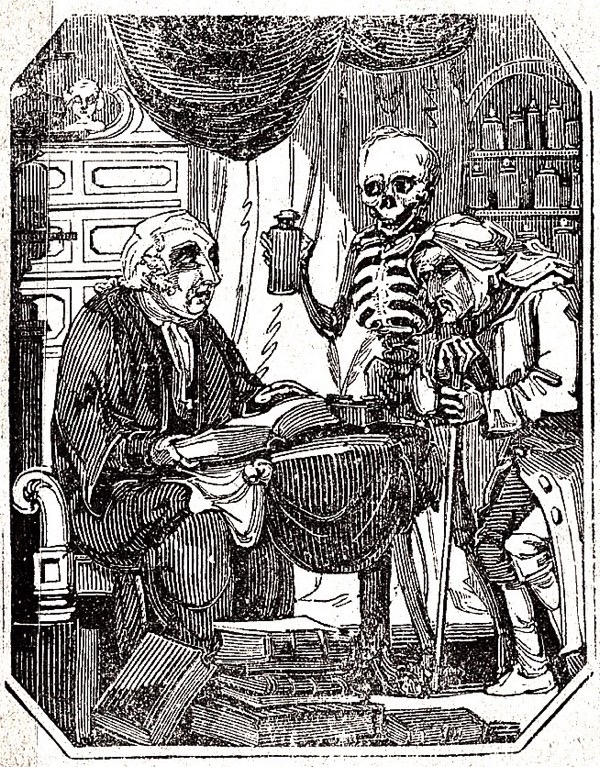

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Councillor or Magistrate

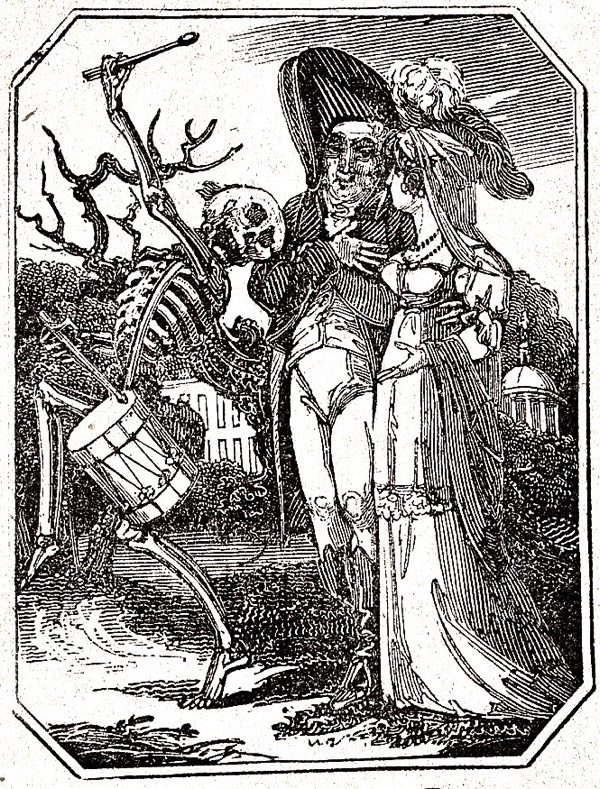

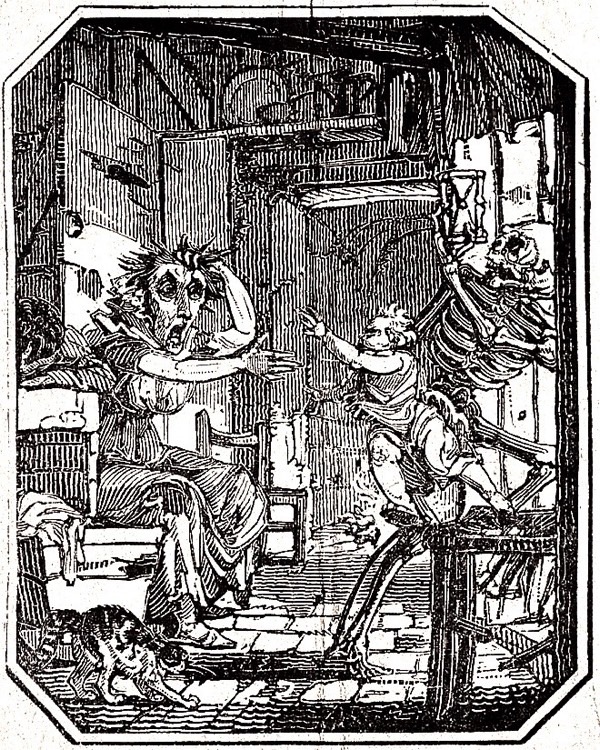

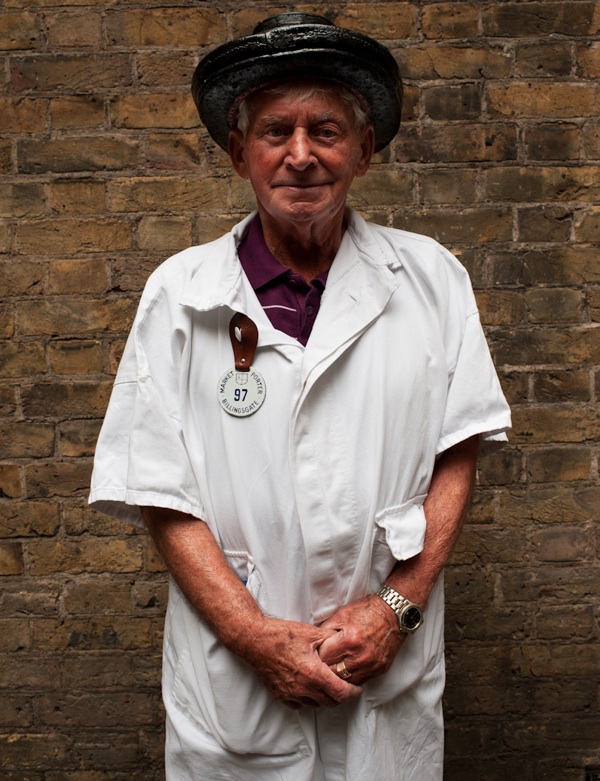

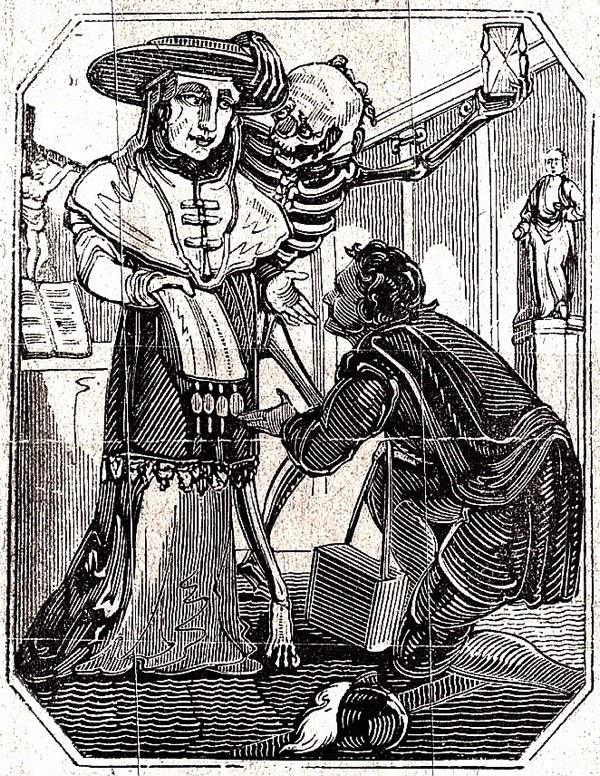

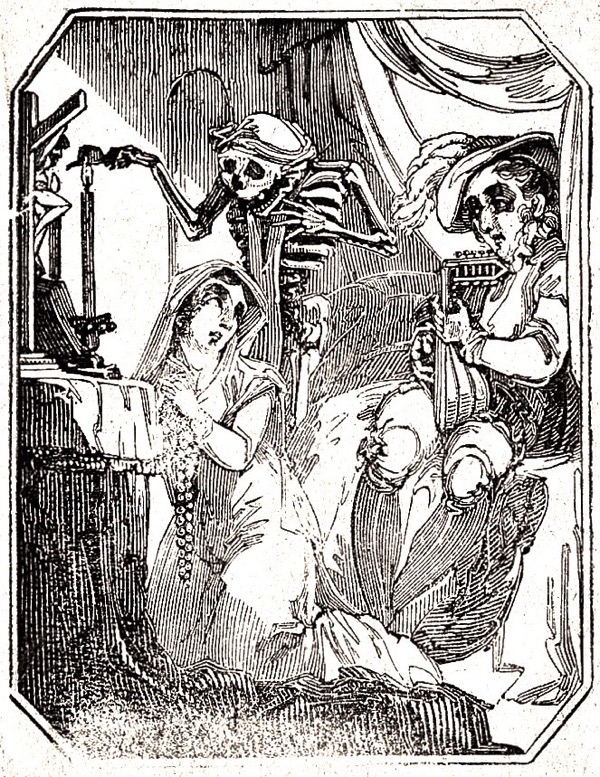

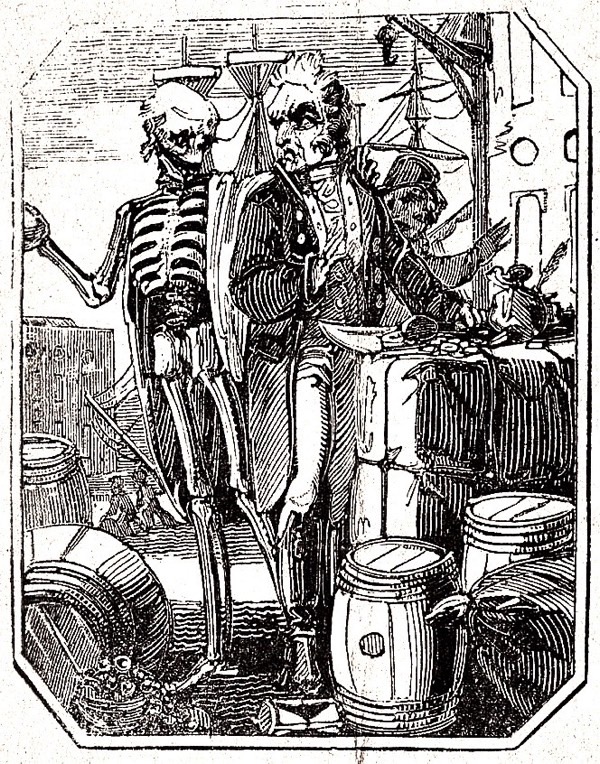

The Porter

The Porter

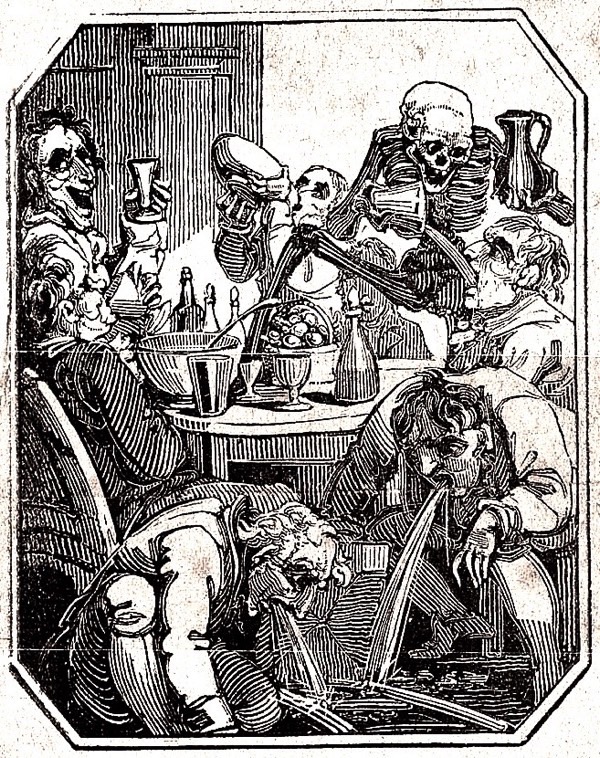

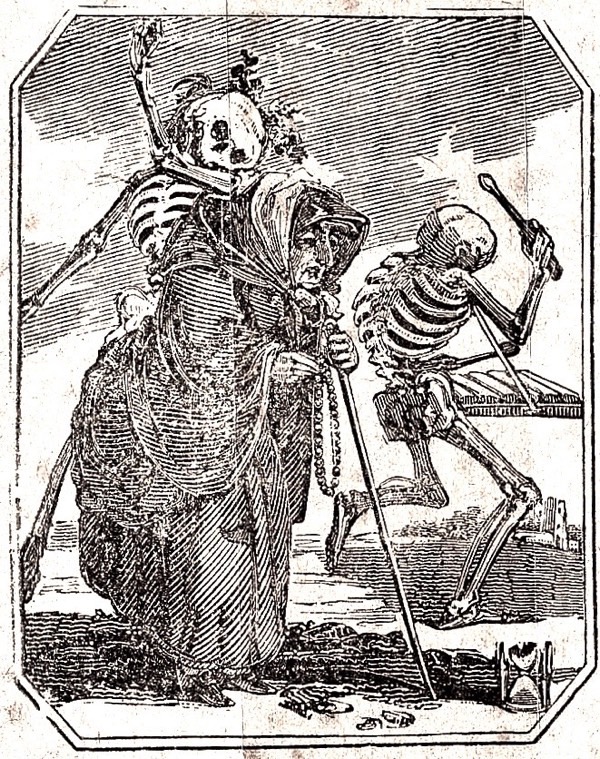

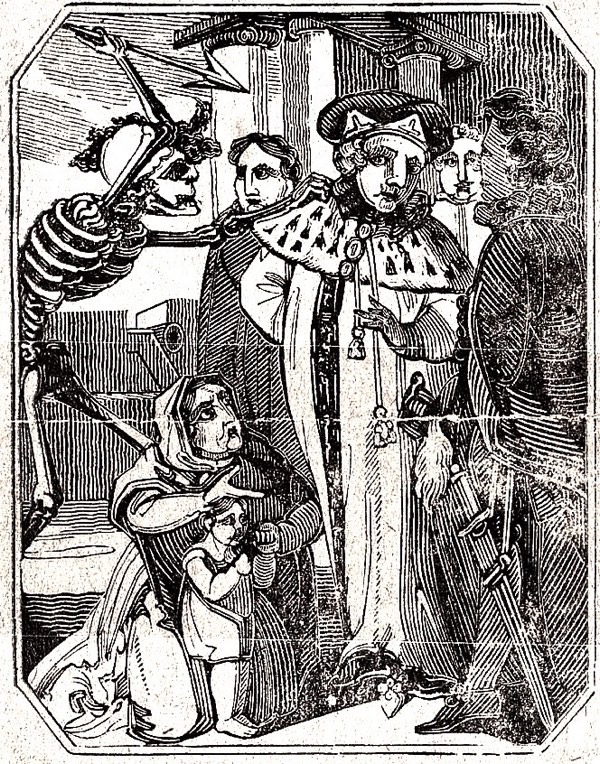

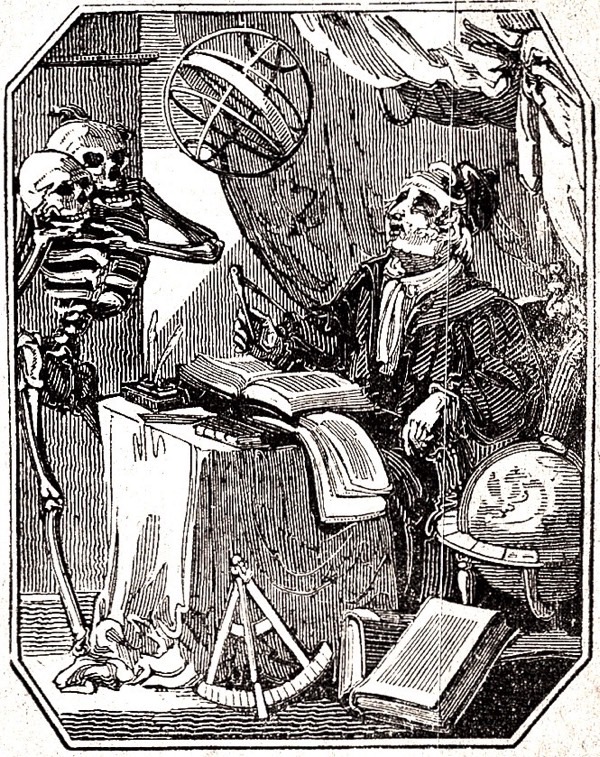

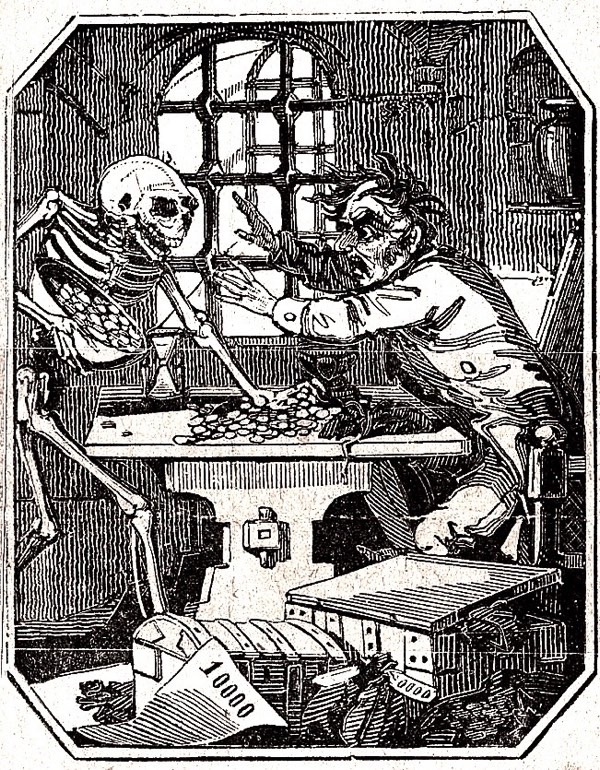

The Miser

The Miser The Gamesters

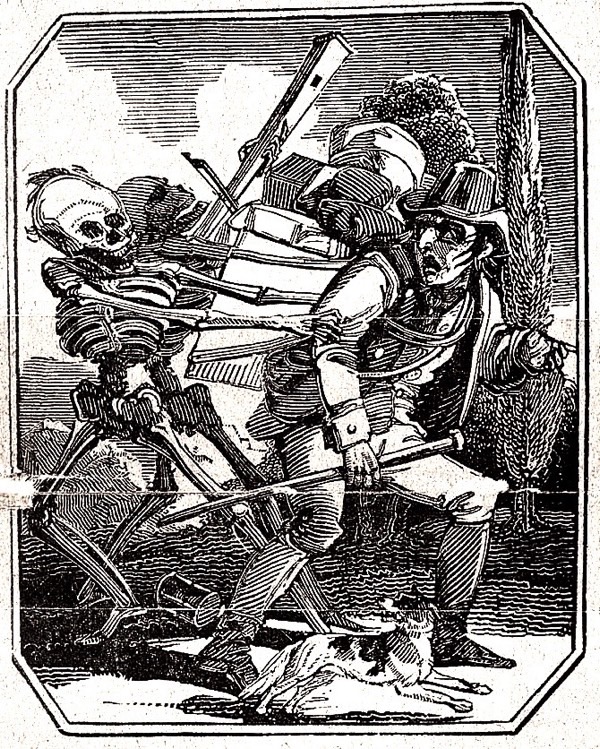

The Gamesters