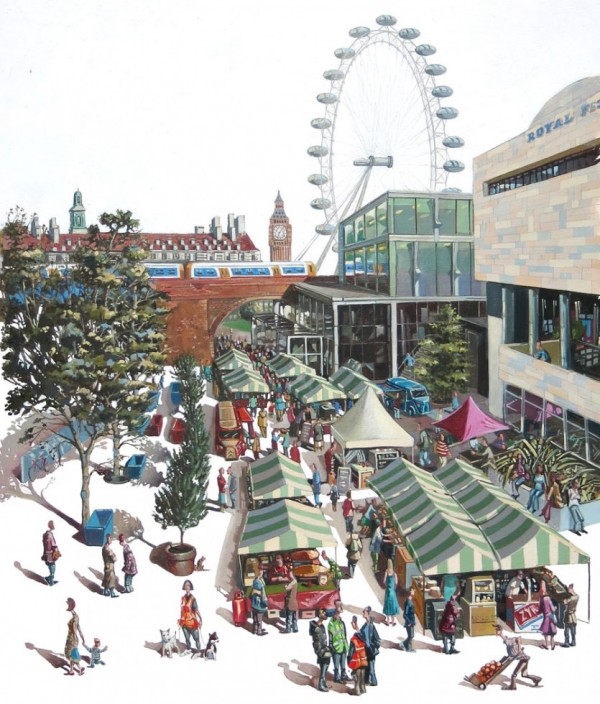

Today it is my pleasure to publish this extract from Volume One of Rodney Archer’s Diary This Strange Re-collection of People (1980-88), in which he recounts a visit to his friend Dennis Severs’ House in Folgate St at Christmas

![Dennis Severs House, Dining Room]()

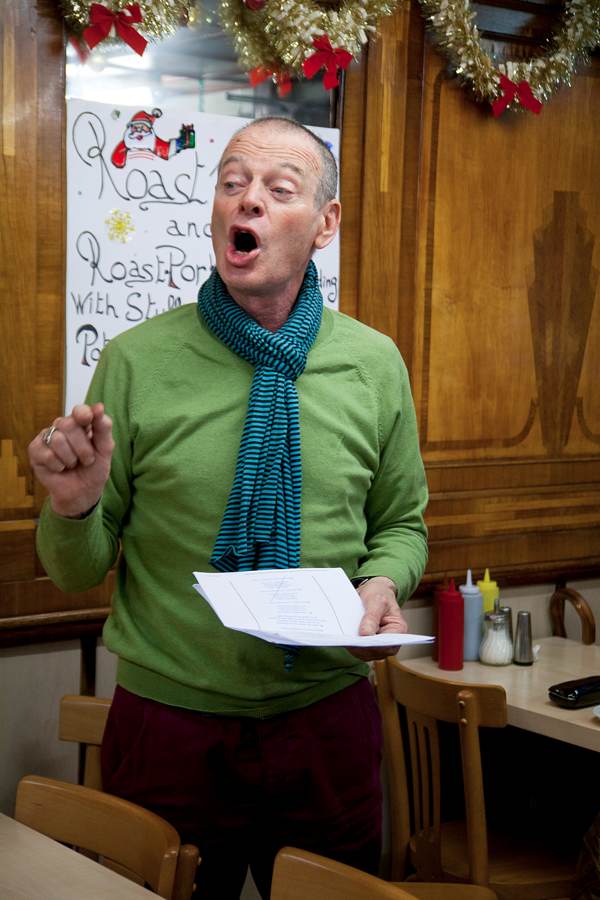

Christmas was for me the best time of the year to visit Dennis Severs in his house, which he shared with Mr & Mrs Jervis and their children in the Liberty of Norton Folgate. The hall was festooned with garlands of holly and ivy and mistletoe. No tinsel marred the scene! The smell of Christmas spices assaulted your nostrils as you entered the front door. Oranges stuck with cloves abounded and the warm hospitality of the Jervises’ was almost palpable. Young boys in velvet waistcoats and knee britches and enchanting young girls in Kate Greenaway muslin dresses would greet you as you entered, offering rum punch circa 1730. Steven, who was eventually to run a restaurant from the ground floor of his house in Church St, had found the recipe in an old eighteenth century cookbook and Dennis was delighted. These children bearing punch were the sons and daughters of neighbours, friends and guests. If you were among the favoured, invited to one of Dennis’ private parties, you had to be prepared to join in and not rock the boat. Everything and everyone was highly organised.

As midnight struck, we were all hurried out of the drawing room and upstairs in the dark to the attic. This was the room in which the sitting tenant, who died within minutes of Dennis signing the contract to secure the house, lived and so promptly perished. It was also the room in which Dorian, the most beautiful of Dennis’ footmen, had his lodging. Towards the end of his brief life, when he was dying of AIDS, Dorian was forced to step into the cupboard when the tours came round to see the room inhabited – in the fiction of it – by Tiny Tim and his father, Bob Cratchet. I am not sure how the Jervises were connected to the Cratchets but what with the arrival of the Spinning Jenny in the early nineteenth century, hard times overtook the silk weavers of Spitalfields and perhaps Mrs Jervis had to take in a lodger? Eventually, Dorian was to move to Church St, two doors away from where I lived with my mother.

“Shhh, don’t talk any of you, shhh… Steven, Arlecchino, Quiet!” Dennis ordered like the matron in charge of a hospital ward. Think Hattie Jacques in ‘Carry on Nurse.’ “Where are Beyond & Ken? Not behind again?!” he asked, wondering if the two performance artists who attended the Hornsey School of Art had lost their way.

Beyond & Ken had lingered too long in the front room on the first floor, called somewhat grandly the ‘piano nobile.’ They were duly fetched and fixed in Dennis’ disapproving eye. All ready and inspected, we followed faithfully and quietly behind as he pushed open the door to his bedroom where we saw the four poster bed covered in red velvet. The bed and canopy had been made from pallets and refuse rescued from the nearby fruit and vegetable market – Dennis was an early recycler.

“Nothing here is real,” he cautioned as Judy (Edgar-in-Elder-St’s first wife) dared to touch a papier mache wig stand. In real life, the bed was Dennis’ own but for the purpose of the pantomime had become… “The bed of Ebenezeer Scrooge, just imagine it,” he said in an almost conspiratorial whisper. Dennis took himself very seriously in these moments and woe betide anyone who did not share his enthusiasm. I wondered why I often felt the need to come out of the illusion he had spent so long in creating. Perhaps, even though I was not a ‘Guardian’ reader, there was something in me that felt too manipulated in these moments? A kind of scepticism mixed with jealousy perhaps? After these many years, now Dennis has departed to join the great Ebenezeer in the sky, I ask his pardon if I did not always share his vision. It was complete but unrelenting and did not allow for one’s own response.

“Imagine,” he continued, “the Ghost of Christmas Past, Present and Future flying overhead.”

Being dyslexic, Dennis had probably never read ‘A Christmas Carol,’ although he would have seen and loved that most famous version with the peerless Alistair Sim as the old miser and, of course, he would have remembered his mother, in the years before she fell ill, reading it to him in the far-removed and warm and sunny clime of California, in the town of Escondido where he had been born.

“You must imagine the snow falling on the rooftops and the frost on the windowpanes of Scrooge’s London house,” she might embroider, delighting her enchanted son, who would one day bring back to the land of its origin the very tale that had been exported so far across the world.

The tape of ‘A Christmas Carol’ would be playing in the background as we all stood, unable to hear it clearly, while Dennis in headmistress mode kept us quiet and I suspect, if we were honest, slightly resentful. Or did the others just feel, “Dear Dennis, he’s so eccentric, how wonderful!” ?

Finally, we were ushered into the drawing room on the ‘piano nobile’ floor where wine glasses and Christmas punch awaited. Dennis proposed a toast to Christmas,

“To Christmas, Ebeneezer Scrooge, the Queen and Spitalfields,”

to which we all added,

“And Dennis,”

“And Dennis,”

“And Dennis.”

Lionheart marred the occasion to my mind – I may have stood outside of it a bit but I never deliberately sabotaged the tale – Lionheart laughed and stabbed out with, “The Queen!” stressing Her Majesty in such a way that it was quite clear what queen he had in mind. There was little love lost between Lionheart and Dennis. There always existed between them that false bonhomie that just manages to control the very real dislike underneath.

Later on, I made moves to go. Phyllis, my mother, had already said goodnight amongst much gooing and gahing, cooing and cahing and was waiting for me downstairs. She was always a bit ambivalent about Dennis and the house he shared with the Jervis family. But she responded to his flattering ways and purred appropriately when stroked. Outside, on the way, home her tarter, or perhaps even her Tartar side, would emerge.

“Well, I’m glad that’s over for another year. I can’t bear those garlands made out of nuts. And, as for the Queen,” she added tetchily.

The garlands in question were draped across the panels in Mrs Jervis’ drawing-room and, from a distance, looked remarkably like the Grinling Gibbons’ carvings found in many a stately mansion and English country house. Up close, however, the illusion vanished and you saw that they were an ingenious hodgepodge of walnuts, almonds and brazil nuts sewn together of an evening by Dennis and his friends. Dennis would often have his most trusted fans around for a night in the smoking room. There, clad cap-a-pie in leather, they would celebrate the joys of friendship in a modern version of the eighteenth century Hellfire Club, sharing a pipe of marijuana and a working class lad or two.

“All is illusion and magic, that is the whole point,” he warned, his voice veering into a higher key as his eagle eyebeam struck the further side of the room, where Ian Gladly had been sighted examining a painting of Gainsborough’s ‘Blue Boy’ too closely. It looked real but how could it be?! Had Dennis raided the Tate Gallery? He was known for his daring.

“Do not all charms fly/ At the mere touch of cold philosophy?” – our host amazed nearly everyone by quoting John Keats. I was not amazed, though I was amused, because I had given Dennis the Keats quotation only a week before when he was complaining about the people who had not “got it” because their reading of ‘The Guardian’ and their critical eye got in the way. Duly chastised, Ian scurried away to refill his empty glass with the Christmas punch circa 1730.

“Dennis, I must go now too. Thank you for a wonderful evening,” I ventured, not realising that I was skating on very thin ice. Dennis replied with suave charm,“Thank you, Rodney, thank you for sticking it out for so long.”

For a moment, I did not feel the pain. I genuinely thought he was thanking me and then I realised that his was as much an attack as Lionheart’s had been. Maybe I had sounded rather grand, rather condescending? – I have that effect occasionally but, on this occasion, I chose my words carefully and was genuinely grateful. Perhaps, and this is more likely, he had picked up on my attitude at a much deeper level? Dennis was not an intellectual in any way. He was very much a creature of instinct, emotion and intuition. And he would sniff out any insincerity on your part and snuff you out immediately like a candle in an eighteenth century wall sconce. When riled he was a veritable tiger. He himself was, however, notoriously insincere. He liked to think of himself as very American and straightforward, but he could smile and be a villain with the best of us. In short, he was a ‘character.’

A group of us had gathered in the hall on the ground floor, fumbling for our coats in the Victorian room which opened off the room in which the Christmas goose sat proudly on its big eighteenth century platter, awaiting consumption.

“The wonderful thing about Denny,” Edgar-in-Elder-St drawled, “is he is a confidence man, a trickster. He sold to the English what was already theirs. It’s better than bottled water – and what a swizz that is – And we fell for it completely. We bought it!”

“Very American, that,” Lionheart added, as he struggled to find Arlecchino’s opera cape which had somehow gone missing.

“Lionheart, where ees my cape, I can’t pass thee market porters dressed as a ‘macaroni’, a kind of Yankee Doodle Dandy! I will be a laughing stocking.”

At this point Arlecchino’s eyes met those of Whitechapel, Dennis’ black and white cat, sitting at the bottom of the stairs and enjoying the festivities. Finally, we found the cape and Arlecchino’s costume was hidden from the amused and even scornful eyes of the market porters, through whom he imagined himself moving so perplexingly.

I had confided to Lionheart earlier that I found the house too much of a museum and a bit too Hollywood for my taste. I can say this without doing Dennis any harm at all because, in all these years, I have only met two other people who felt the same as I did. Dennis prided himself on being the real thing. The ‘real thing’ in terms of taste and decoration was distinguished by him as the ‘Joan Collins School of Decoration’ versus the ‘Queen Mother’s School of Decoration.’ There was even a television programme on the area in which Dennis and William Candy, the architectural-historian-who-wore-a-kilt-and-sported-a-pigtail, were seen wandering around Spitalfields and Brick Lane, past the Jewish Soup Kitchen for the Poor, along the Moorish Arcade in Fashion St, examining different facades and door fronts, lintels and fanlights, approving or disapproving as the Queen Mother dictated.

Our door front had been a thing of beauty and a joy forever, until we had to have it taken away and repaired and, in that process, hundreds of years of paint was stripped off – O, God, forgive me – to reveal the original contours sleeping unsuspected beneath and then the door became a bad thing. In vain did I argue that mother and I had very little choice in the matter – the architect insisted - but Dennis would have none of it, and so Phyllis and I had the indignity of hearing Dennis and William Candy, the architectural-historian-who-wore-a-kilt-and-sported-a-pigtail, stop in front of our door and exclaim to the nation in a televised documentary, “This is very much an example of the Joan Collins School of Decoration! We prefer the Queen Mother’s School.” They both shook hands on it and that was that. Our fate was sealed.

My mother and I had been consigned to that uncomfortable circle of Dante’s Inferno shared by homosexuals and failed house restorers. Though he would have been mortally offended to hear it, Dennis’ house had a bit too much of the ‘Metro Goldwyn Mayer School of Decoration’ itself but God protect you if you ever hinted so much. He was not only very sensitive in these matters but also – and the two go together like a horse and eighteenth century carriage – deeply insecure.

I had previously joked with Lionheart about Dennis’ ordering us all about as if we were servants, “Now those of you who are sitting in them, bring the eighteenth century chairs up to the drawing room.”

“Dennis, which ones are they?” I asked.

“O, Rodney, really! The eighteenth century chairs have no arms, thereby enabling Mrs Jervis and her daughter, Sophia, to sit with their farthingales and hoopskirts unimpeded,” he emphasised, somewhat pedantically in his short quick trans-Atlantic accent.

Well, lah-di-bloody-dah, my dears, and God bless you all – Dennis, Ebeneezer Scrooge, the Queen and Spitalfields!

![Dennis Severs House, Xmas 2015]()

![Dennis Severs House, kitchen]()

![Dennis Severs House, Lekeaux Room]()

![Dennis Severs House, Dickens Room]()

Text copyright © Estate of Rodney Archer

Photographs copyright © Dennis Severs House

Dennis Severs House, 18 Folgate St, Norton Folgate, E1 6BX

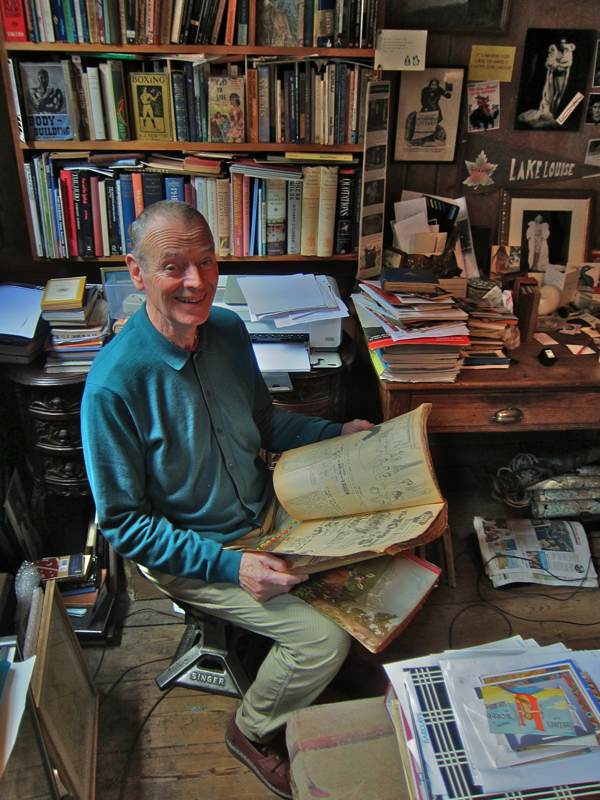

Rodney Archer deposited his diary in the archive at the Bishopsgate Institute earlier this year

You might also like to read

So Long Rodney Archer

Dennis Severs Menagerie

A Walk With Rodney Archer

Isabelle Barker’s Hat

Rodney Archer’s Scraps

Simon Pettet’s Tiles

Spitalfields Market

Spitalfields Market

![Demolition Image[1]](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Demolition-Image14-600x417.jpg)