![L1000813]()

.

Longer ago than I care to admit, fortune led me to an old theatre in the Highlands of Scotland. Only now am I able to reveal some of my experiences there and you will appreciate that discretion prevents me publishing any names lest those who are still alive may read my account.

It was a magnificent nineteenth century theatre, adorned with gilt and decorative plasterwork. Since this luxurious auditorium with boxes, red drapes and velvet seating was quite at odds with the austere stone buildings of the town, it held a cherished place in the affections of local theatregoers who crowded the foyers nightly, seeking drama and delight.

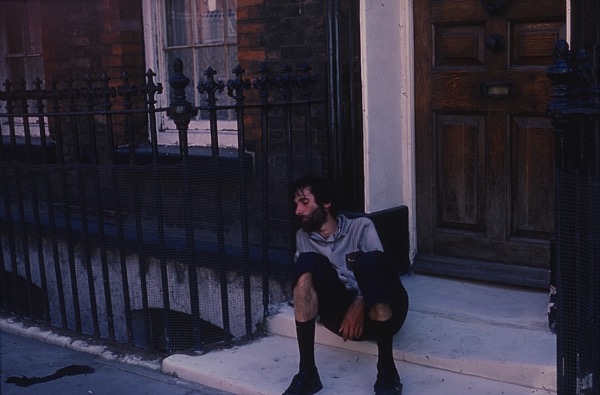

Although it is inexplicable to me now, at that time in my life I was stage struck and entirely in thrall to the romance of theatre. Perhaps it was because of my grandfather the conjurer who died before I was born? Or my love of puppets and toy theatres as a child? When I left college at the beginning of my twenties, I refused to return home again and I did not know how to make my way in London. So I was overjoyed when I landed a job at a theatre in the north of Scotland. I packed my possessions in cardboard boxes, took the overnight train and arrived in the frosty dawn to commence my adult life.

As soon as it was discovered I had a literary education, I was assigned the task of organising the script and writing the ‘poetry’ for the annual pantomime, which that year was Dick Whittington. In the theatre safe I found a stash of tattered typescripts dating back over a century, rewritten each time they were performed. These documents were fascinating yet barely intelligible, and filled with gaps where comedians would supply their own patter. I discovered that the immortals, in this case Fairy Bow Bells and Old King Rat, spoke in rhyming couplets. Yet to my heightened critical faculties, weaned on Shakespeare and Chaucer, these examples were lame. So I resolved to write better ones and set to work at once.

.

Fairy Bow Bells:

In the deepest, bleakest Wintertime,

I welcome you to Pantomime.

Here is Colour! Here is Magic!

Here is Love and naught that’s Tragic.

.

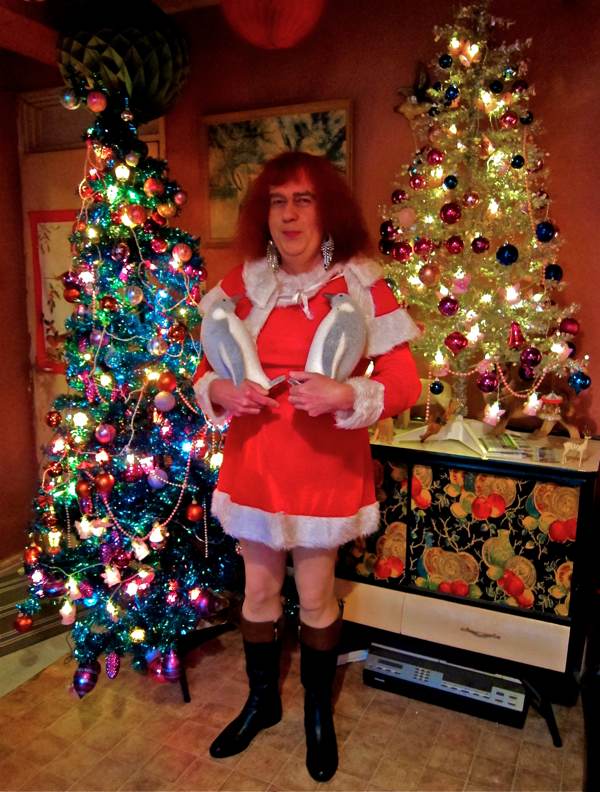

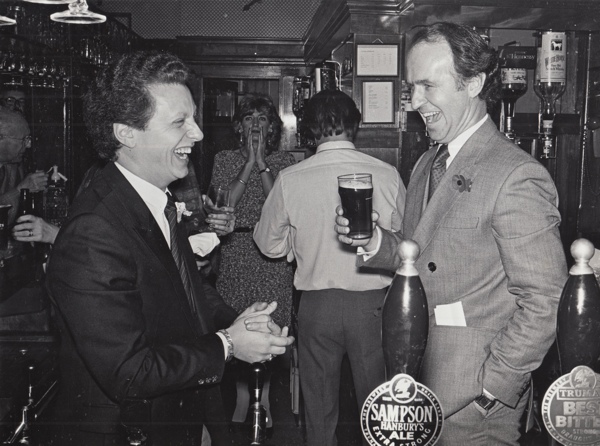

‘You are here to learn the art of compromise, and how to pour a decent gin and tonic, darling,’ the director informed me at commencement with a significant nod of amusement when I submitted my work. I tried to raise an amenable smile as I served the drinks, but it was a line delivered primarily for the benefit of the principals gathered in the tiny office for a production meeting. These were veterans of musical comedy and summer variety who played pantomime every year, forceful personalities who each brought demands and expectations in proportion to their place in the professional hierarchy, with the ageing comedian playing Dame Fitzwarren as the star. Next came the cabaret singer and dancer playing Dick Whittington and then the television personality playing Tommy the Cat.

It was my responsibility to manage auditions for the chorus of boy and girl dancers, sifting through thousands of curriculum vitae and head-shots to select the most promising candidates. Those granted the opportunity were given ten minutes to impress the musical director and the choreographer with a show tune and a short dance sequence. Shepherding them in and out of the room and handling their raw emotions proved a challenge when they lost their voices, broke into tears or forgot their routines – or all of these.

The cast convened for a read-through in the low-ceilinged rehearsal room in a portacabin in the theatre car park. Once everyone had shaken hands and a cloud of tobacco filled the room, the director wished everyone good luck and, turning to me before leaving the room, declared loudly ‘Don’t worry, darling, they know what to do!’, employing the same significant nod I had seen in the production meeting and catching the eye of each of the principals again.

We all sat down, I handed round the scripts and the cast turned to the first page. The principals gasped in horror, exchanging glances of disbelief and reaching for their cigarettes in alarm. Dame Fitzwarren blushed, tore out a handful of pages and spread them out on the table, muttering, ‘No, no, no,’ to himself in condemnation. I sat in humiliated silence as, in the ensuing half hour, my sequence of pages was entirely rearranged with some volatile horse trading and angry words. Was this the art of compromise the director had referred to? I had organised the scenes in order of the story – no-one had explained to me that in pantomime the sequence of opening scenes are a device to introduce the principals in order of status from the newcomers to the seasoned stars. Yet even if I had understood this, it would have made little difference since the cast were all unknown to me.

On the second day, the floor of the portacabin was marked with coloured tapes which indicated the placing of the scenery and it was my job to take the cast through their moves. Dame Fitzwarren was keen to teach his comedy kitchen sequence to the two young actors playing the broker’s men. Once he had walked them through, I suggested we should give it a go. ‘No,’ he said, ‘That was it, we did it.’ I understood that, in pantomime, comedians only rehearse their sequences once as a matter of honour.

The little theatre owed its existence to the wealth of the whisky distilleries which comprised the main industry in the town and many of the directors of these distilleries were members of the theatre board. In particular, I remember a diminutive fellow who made up for his lack of height with an abrasive nature. He confronted me on the opening night, asking ‘Is this going to be good, laddie?’ My timid reply was, ‘It’s not for me say, is it?’ ‘It had better be good because your career depends upon it,’ was his harsh response, poking me in the gut with his finger.

In fact, Dick Whittington – in common with all the pantomimes at that theatre – was a tremendous success, playing to packed houses from mid-December until the end of January. The frantic energy of the cast was winning and the production suited the mechanics of the building beautifully, with brightly coloured flying scenery, drop-cloths and gauzes. The audience gasped in wonder when Fairy Bow Bells waved her wand to conjure the transformation scene and booed in delight when Old King Rat popped up through a trap door in a puff of smoke. They loved the familiar faces of the comedians and laughed at their routines, even if they were not actually funny.

Given the punishing routine of three shows a day, the collective boredom of the run and the fact that they were away from home, the pantomime cast occupied themselves with a rollercoaster of affairs and liaisons which only drew to an end at the final curtain. Once Dick Whittington unexpectedly stuck her tongue down my throat in the backstage corridor on New Year’s Eve and Dame Fitzwarren locked the door of the star dressing room from the inside, subjecting me to his wandering hands when I came to discuss potential cuts in the light of the stage manager’s timings. I found myself entering and leaving the building through the warren of staircases and exit doors in order to avoid unwanted attention of this nature. The gender reversals and skimpy costumes contributed to an uncomfortably sexualised environment which found its expression on stage in the relentless innuendo and lewd references, all within an entertainment supposedly directed at children. ‘Thirty miles to London and no sign of Dick yet!’

I shall never forget the musical director rehearsing the little girls in tutus from a local stage school who supplied us with choruses of sylphs on a rota to accompany Fairy Bow Bells. ‘Come along, girls,’ he instructed the children, thrusting his chest forward and baring his dentures in a frozen smile of enthusiasm,’ Tits and teeth, tits and teeth,’ using the same exhortation he gave to the adult dancers.

Our version of Dick Whittington contained an underwater sequence, when Dick’s ship was wrecked, permitting the characters to ‘swim’ through a deep sea world which was given greater reality by the use of ultra-violet light and projecting an aquarium film onto a gauze. This was also the moment in the show when we undertook a chase through the audience, weaving along the rows. Drawing on the familiar tradition of pantomime cows and horses – and perhaps inspired by the predatory nature of the environment – I devised the notion of a pantomime shark in a foam rubber costume that could chase the characters through the front stalls and around the circle to the accompaniment of the theme from Jaws. I had no idea of the pandemonium that this would unleash but, each night, I made a point of popping in to stand at the back to enjoy the mass-hysteria engendered by my shark.

The actor playing Old King Rat had previously been cast as Adolphus Cousins in Major Barbara, so I decided to exploit his classical technique by writing a death speech for him. It was something that had never been done before and this is the speech I wrote.

.

Old King Rat:

This is the death of Old King Rat,

Foiled at last by Tommy the Cat.

No more nibbles, no more creeping,

No more fun now all is sleeping.

This is the instant at which I die,

Off to that rathole in the sky…

.

Naturally this was accompanied by extended death-throes, with King Rat expiring and getting up again several times. Later, I learnt my speech had been pirated by other productions of Dick Whittington, which is the greatest accolade in pantomime. Maybe it is even now being performed somewhere this season?

In subsequent years, I was involved in productions of Cinderella and Aladdin, but strangely I recall little of these. I did not realise I was participating in the final years of a continuous theatrical tradition which had survived over a century in that theatrical backwater. I did not keep copies of the scripts and the fragments above are all I can remember now. I do not know if I learnt the art of compromise but I certainly learnt how to pour a stiff gin and tonic. And I learnt that in any theatre there is always more drama offstage than onstage.

.

![L1000812]()

.

You may also like to read about

The Gentle Author’s Childhood Christmas

19 Mile End Place

19 Mile End Place