At the opening of Doreen Fletcher’s RETROSPECTIVE, I publish this interview in which Doreen tells her story in her own words.

All are welcome tonight at the Private View of Doreen Fletcher’s RETROSPECTIVE at Nunnery Gallery, Bow Arts, Thursday 24th January from 6pm. The exhibition runs until 24th March.

I am IN CONVERSATION WITH DOREEN FLETCHER on Wednesday 30th January 7pm at Nunnery Gallery, showing the paintings and telling the stories. Click here for tickets

![DF]()

Portrait of Doreen Fletcher in her studio by Stuart Freedman

Doreen Fletcher - Looking back, I think I was attracted to painting even from the age of four or five. I loved colour and my dad used to take me to the local toy shop where I always insisted on the best quality paints. I was an only child, born into a working class family, and my parents were – as you might say these days – semi-literate. Consequently, from the age of about eight years old, I took responsibility for helping them out in dealing with officialdom, not unlike – I suppose – immigrant children in the East End today whose parents have limited English.

My mum and dad were very loving, and keen for me to have the opportunities they had missed. When I was five, I was bought a set of encyclopaedias from a salesman selling door-to-door on the never-never. It had colour reproductions of famous paintings such as Constable’s ‘The Hay Wain’ by Constable and Turner’s ‘The Fighting Téméraire’ and I thought they were wonderful.

I passed my eleven-plus exam but I had a very difficult time at grammar school because – although I was clever and always in the top six of the top stream – I came from the wrong side of the tracks. I felt I had to pretend I was from somewhere else, because most of the pupils came from professional middle-class families. Consequently, I could not invite school friends to our tiny terraced home. I did not speak with the right accent, have the social ease of the other children or possess their cultural knowledge.

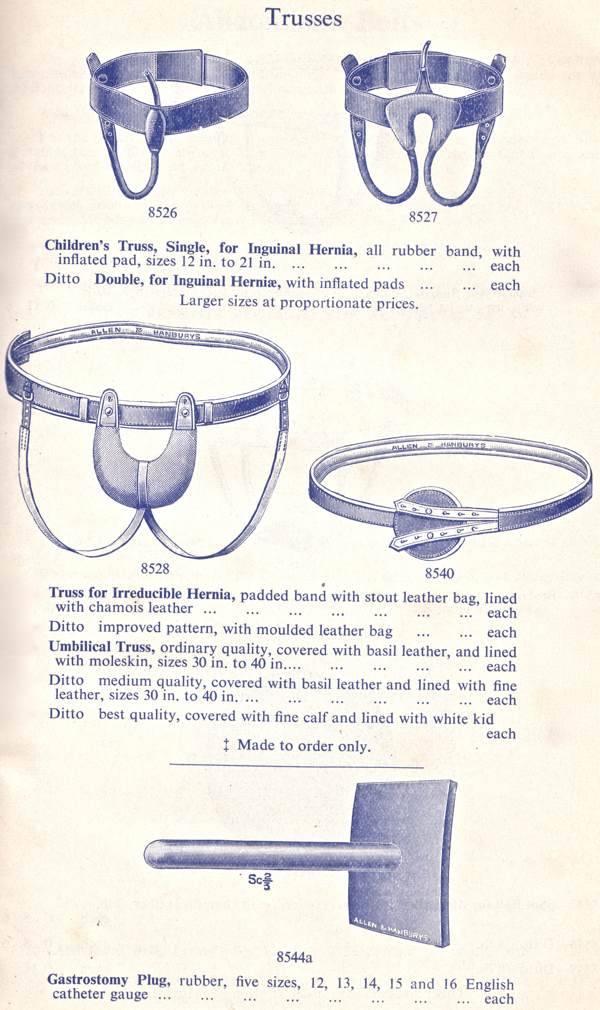

The art room was a refuge for me because there I could express myself fluently under the expert tutelage of the art teacher Mr Hanford. He had trained at the Royal Academy School and was probably the only teacher of any influence I ever listened to. I loved Fridays when there was a two hour after-school art club. It was at one of these sessions that Mr Hanford advised against using black paint straight from the tube. To this day, I mix ultramarine and burnt umber for a warm black and raw umber and indigo for a cool black.

The Gentle Author - What work did your parents do?

Doreen Fletcher – Alice, my mother, worked in a munitions factory during the war and then became a domestic servant afterwards. It gave her ideas about not putting the newspaper or ketchup bottle on the table and she adopted ‘healthy eating,’ much to my irritation. She was also particular about keeping the front step, windows and net curtains clean. Colin, my dad, started off as a farm worker. He wanted to be a vet but due to illness he missed a year’s education at seven years old which meant that he left school hardly able to read or write.

After I was born, we moved from the village of Barlaston to Newcastle-Under-Lyme because my dad could earn more money in the town. In the late fifties, when the government erected pylons across the nation, he worked on the construction of these and later he found employment laying pipes for North Sea Gas. When my dad was fifty-seven, he had a brain haemorrhage at work, probably due at least in part to the vibrations of the pneumatic drill. He did not work again after that.

The Gentle Author - What was the first landscape that you knew?

Doreen Fletcher – It was composed of greys and browns – soot-streaked streets with sparrows and pigeons. I used to long for colour, for tinsel, for fairy lights and fairgrounds. Yet although I grew up in a two-up-two-down terrace in Stoke-on-Trent, every Sunday my parents took me on excursions by bus into the country, a different destination each time. This was rare at the time and I think it revealed their great sensitivity and care.

These trips were always accompanied by the purchase of a quarter pound of sweets and latterly, a brownie box camera that took tiny black and white photos. I liked going for long walks alone too. I was always looking and observing the variety of houses lining the streets I wandered through. Sometimes I roamed the countryside as well, walking along busy trunk roads. These days eyebrows might be raised, but there was nothing unusual in seeing unaccompanied children exploring back then. I loved my solitary walks.

The Gentle Author – What took you away from the Potteries?

Doreen Fletcher – I did not like living in a small town, it lacked cosmopolitanism. I hated the social constrictions and the pettiness I encountered. After A Levels, I decided I to study a subject that would earn me a living, so I enrolled on Bsc Sociology Course at North Staffordshire Polytechnic in Stoke. I have always been fascinated by other people’s lives, attitudes and behaviour.

However it proved a disastrous choice for me because the course dealt mostly with statistics and their interpretation. I did not even last two terms. So I went to work in a local tile factory – of which there were plenty in those days – where my job was sorting broken tiles. After six months I left, realising there was no future in it for me.

I knew my vocation was to be an artist. I spent a very happy year doing a foundation course in Newcastle-Under-Lyme. I felt at home there. I was comfortable and totally at ease in the chaotic atmosphere of the leaky portacabins that served as our studios. For the only time in my life, I did very little work. Instead I enjoyed making friends and formed a close relationship with a fellow student. Together we moved to London in 1972 where he attended Wimbledon School of Art and I worked as an art school model.

The Gentle Author - Did you apply to art school?

Doreen Fletcher – Yes, I applied to study at Croydon College. Even then, I was very independently minded and did not want a structured degree course where I might be expected to conform to a ‘house style’. At this point, I was painting quite a lot of self-portraits and still lifes.

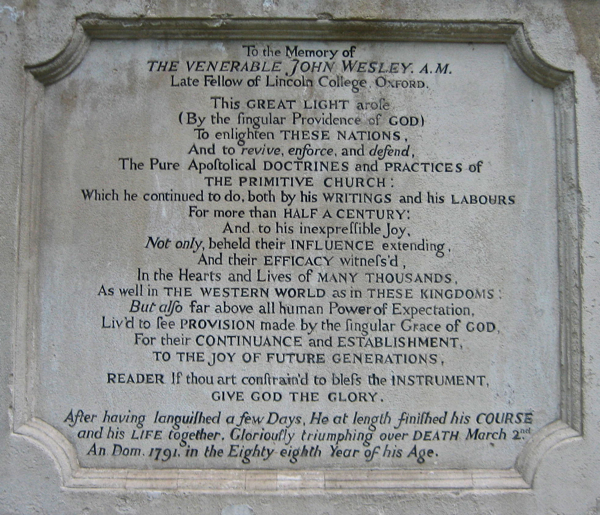

One day in late 1973 I saw an exhibition of paintings of Mow Cop by Jack Simcock in Cork Street. Mow Cop was a hilltop village not far from my home. In Newcastle-under-Lyme, if I leaned out of my bedroom window at a dangerous angle, I could just see the Victorian folly on the summit of Mow Cop in the distance.

The houses were built out of Peak District sandstone and local millstone grit. The place was bleak and dour. I was captivated, deciding then that I wanted to be an urban landscape painter, recording my own environment.

The Gentle Author - Where did you live when you first came to London?

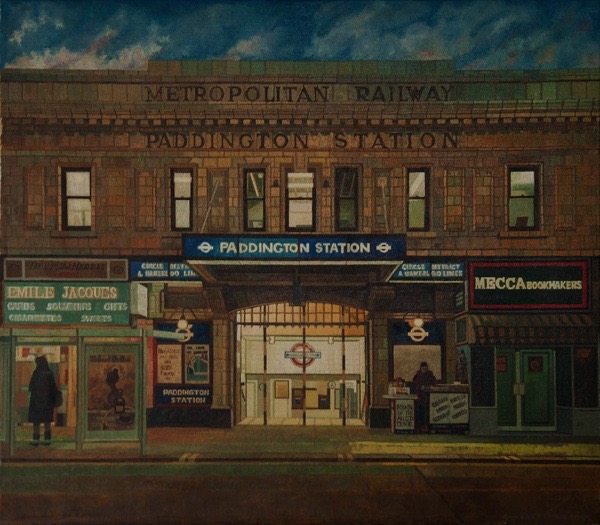

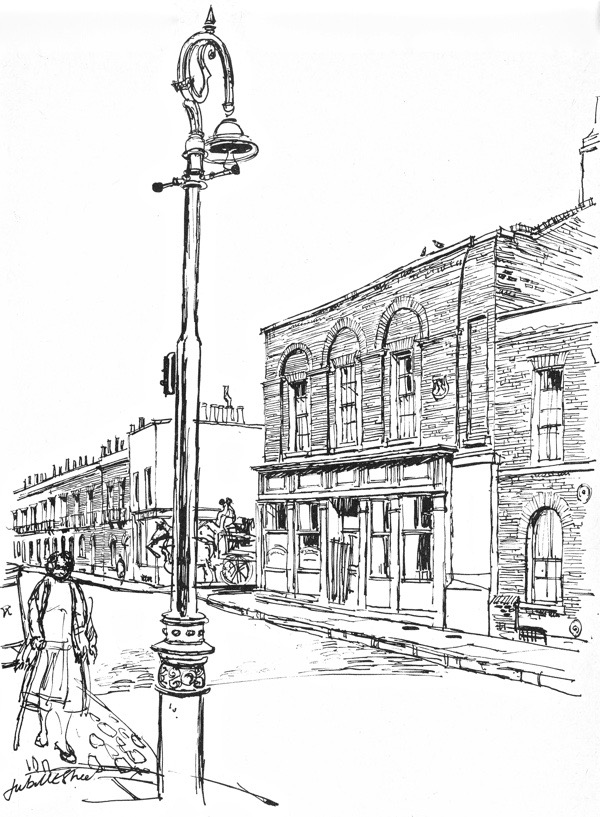

Doreen Fletcher – To begin with, I stayed around Wimbledon, then I spent seven years living in Paddington where my fascination with urban scenes escalated. Coming from a small town in the North, it was an exciting place to be. I was close to the Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, Notting Hill Gate and Portobello Road. I started painting local landmarks, the Electric cinema and the Serpentine boathouse. Then I became interested in Underground stations at night, Bayswater and Paddington. This project continued when I moved to the East End.

The Gentle Author - What brought you to the East End?

Doreen Fletcher – At that time artists were attracted to live and work in the East End because of the cheap studio space that was available. It was easy to rent because the local population were moving out and and artists were happy to live in dilapidated accommodation if it gave them room to work. Before long, a mutually supportive community of artists developed around Bow, Stepney and Mile End.

The Gentle Author – How do you remember the East End then?

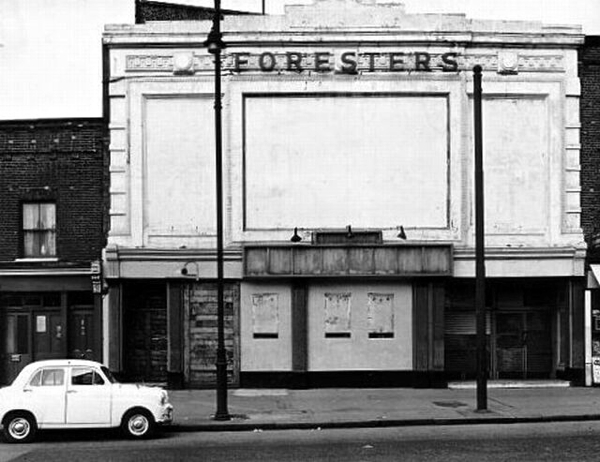

Doreen Fletcher – I noticed the skies first, open and dramatic as they advanced into Essex. There were corrugated fences everywhere, still bombsites where buddleia proliferated and a few prefabs inhabited by artists. There was an openness in the streets which has since gone, now every corner has been built up and every vacant space filled.

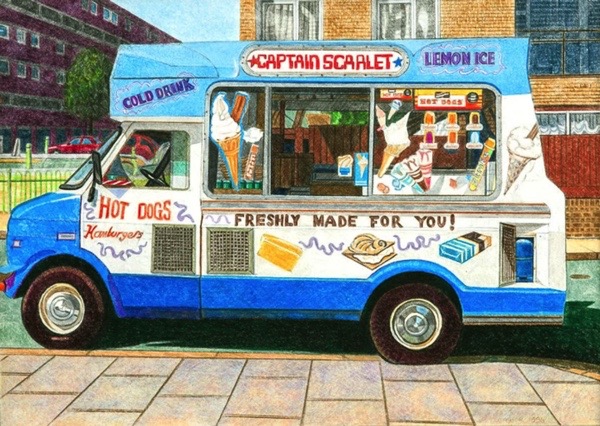

Yet the distinctive quality of light remains particular to this part of London, a luminescence generated by the proximity of the river. I loved it here because I had had enough of the West End. It felt to me as if I were returning home. Like Stoke, the East End was predominantly working class and also had once been an important centre for industry. Corner shops and tiny pubs proliferated among street markets.

The Gentle Author - Why did you start painting the East End?

Doreen Fletcher – I was excited visually by being somewhere new to me yet that also reminded me of where I grew up. In the Potteries, the town planners’ ethos was ‘If it’s old, let’s sweep it away’ – regardless of its cultural and historical significance. I saw the same fate awaiting the East End. The first painting I did here was the bus stop in Mile End in 1983 and then Rene’s Café next.

The Gentle Author – Was this your full time occupation?

Doreen Fletcher – I was working as an artists’ model in an art school. It was the most boring job you could imagine, but I stuck at it during term-time so I could have periods of full-time painting. I was able to keep myself by working three days a week as a model.

The Gentle Author - How central to your life were your paintings at that time?

Doreen Fletcher – Painting was the focal point of my life. My studio was a small room at the top of a run-down three-storey house in Clemence Street. It faced north so the light was good for painting.

I walked around the East End at different times of day and in different weathers. Eventually a particular scene imprinted itself on my mind that could have potential as a painting. I did thumbnail sketches and took a photograph. Once I had gathered this information, I made a detailed drawing as a basis for the painting. This might evolve over a period of months or even years, as the tension built up between my need to represent reality and the demands made by the painting itself. I always struggle to resolve a picture in an abstract way as well as portraying a subject. To this day,I follow this methodical process to make a painting.

I worked a minimum of twenty-eight hours a week, a target I still adhere to. I was determined not to become a Sunday painter.

The Gentle Author - Did you have ambition for this work?

Doreen Fletcher – Yes and I did have some limited success in the eighties showing within the borough, receiving a few grants and being accepted in open exhibitions such as the Whitechapel and the London Group. Companies bought work from time to time and local people appreciated my paintings, but there was little interest from any critics or commercial galleries.

The Gentle Author - Did you pursue other avenues to get recognition for your work?

Doreen Fletcher - Once a month, I used to send off slides in response to competitions and requests for submissions in Artists’ Newsletter. It was time-consuming and costly without reward.

The Gentle Author - How did you maintain morale through those twenty years?

Doreen Fletcher – I am an optimist and I remained optimistic up until the late nineties, when my work grew increasingly unfashionable due to the rise of conceptual art. It became more difficult to find any places where I could exhibit my work that would even accept representational painting. My work was simply out of fashion My interest in the East End was waning too, as Canary Wharf transformed into a financial metropolis. I found I did not know what to paint any more. It felt as though a period of my life was coming to an end.

The Gentle Author - What made you feel that?

Doreen Fletcher - The East End was changing in a way that I could not understand or portray. The new buildings were densely packed, destroying the distinctive sense of place and community. At first, I was interested in the construction – on the Isle of Dogs for instance – but once it was finished there were just too many people and too much architectural uniformity.

The Gentle Author - Were there changes in your life too?

Doreen Fletcher – I grew more involved in teaching art to youngsters with special needs, taking a part-time job in further education. I became more interested because I found I was good at it and my teaching work was appreciated. Gradually, I worked more in the administrative side of education, supporting other lecturers.

The Gentle Author - Did you find that satisfying?

Doreen Fletcher – Yes, I was earning a salary and contributing to the community. It was rewarding to be working with other people after my years of isolation. I enjoyed participating in the local community rather than being an observer.

The Gentle Author - Once you had completed nearly twenty years of painting the East End, what were your feelings about that series of work?

Doreen Fletcher – I did not realise that I was creating any kind of social document at the time because I was so absorbed with each painting, each one constituting such a lot of work. I had tried very hard to get my pictures out there and get them seen. I had hoped for some kind of recognition. I was never ambitious in terms of international recognition but I did feel that the work was good enough to be recognised more than it was.

The Gentle Author - Were you disappointed?

Doreen Fletcher – Yes. I remember the day I made a conscious decision to pack away my paints. It was November 16th 2004. I said, ‘That’s it! I am not going to paint again.’ I had no knowledge that I was undertaking a journey and enduring a struggle that other artists in the East End had already experienced. If I had been aware of the East London Group and their example, I might have had the heart to continue.

The Gentle Author - Do you think your project reached its culmination?

Doreen Fletcher – At the time I did not think so, I believed I had done all that work for nothing. But looking at the work again, I am very glad I did it. I think it was important that I recorded something which has now vanished.

The Gentle Author - Do you think you evolved as a painter by doing this work?

Doreen Fletcher – If I had I been taken on by a gallery, I might have developed more as a painter. Instead, I think I found a method of working that suited what I was doing and I stuck with it. Maybe with a bit more encouragement I would have done what I am doing now, since I have come back to painting.

The Gentle Author – How do you judge if one of your paintings is successful?

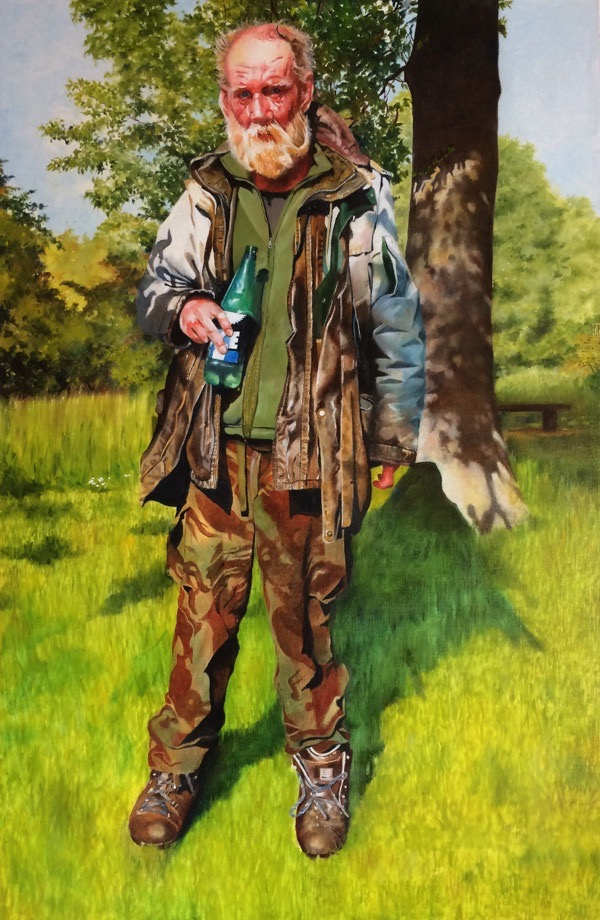

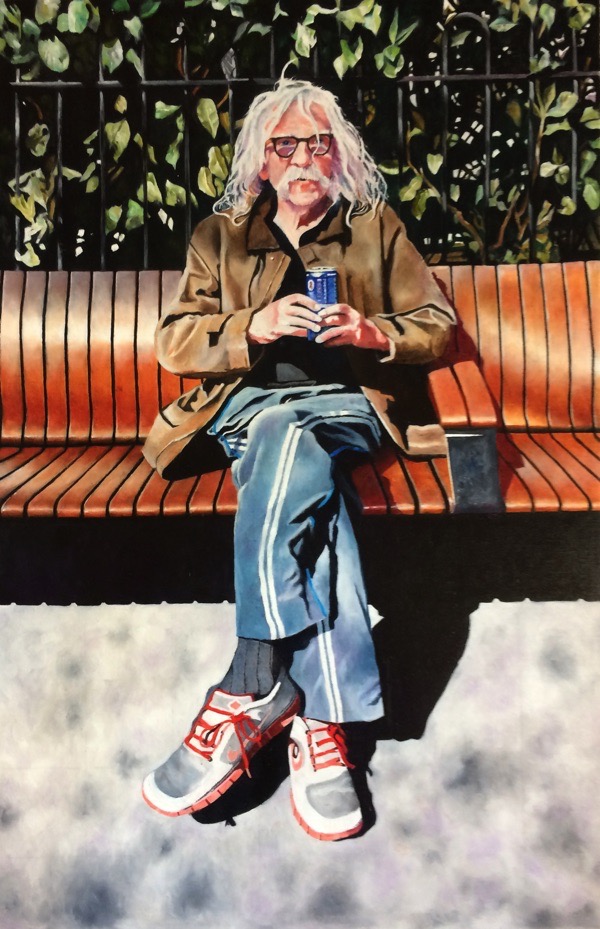

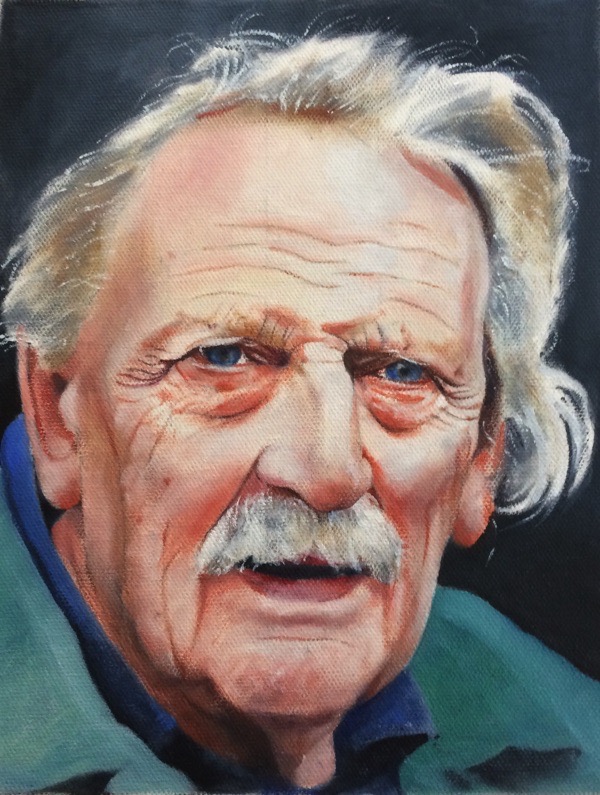

Doreen Fletcher – A painting is successful for me when I believe I have captured an essence of a place in a moment. A picture must sit comfortably and solidly on the canvas. My concern as an artist is with the pockets of life that we ignore.

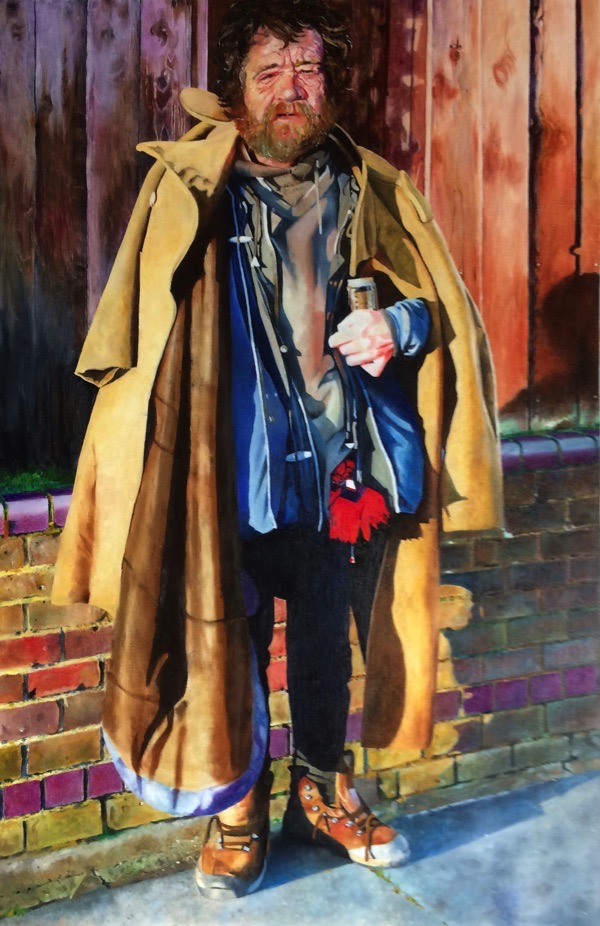

Now I have started painting again and the series of pictures I have been working in the last two years are the result of having lived in East London for thirty-five years. I have been reflecting on how much remains from the early years and come to appreciate how those people who still live here have adapted to the changes.

In the early eighties, this part of London was run down and very few people chose to be here. Some streets and buildings remain as reminders of that era, left to compete with new concepts of London that have emerged since the closing of local industries and the rise of corporate culture. In representing their utilitarian quality, I envisage my subjects not only as reminders of the past but also as active survivors struggling positively to find a place in a world changing beyond recognition.

I am a painter concerned with environments that are or have been inhabited. I try to resolve the struggle between how I see things and with abstraction, where the pictorial demands of structure, organisation and balance hold sway. My work is carried out slowly and methodically using a range of techniques to communicate a place of quietude and serenity. The difference between the work I am making today and the work I was doing before is that now I am a participant, no longer only an observer of East End life.

.

![9780995740143]()

.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER A SIGNED COPY OF DOREEN FLETCHER’S BOOK FOR £20

.

![SLB-2]()