David Buckman profiles Barnett Freedman (1901–1958) who was born in Stepney. A major retrospective, Barnett Freedman – Designs for Modern Britain opens at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester on 14th March and runs until 14th June.

I am giving a lecture about the work of Barnett Freedman and other twentieth century artists, Street Life: Painting the East End , at Pallant House on 30th April Click here for tickets

![21]()

Barnett raises his hat in Kensington Gardens to celebrate designing the Jubilee stamp for George V

Odds were heavily stacked against Barnett Freedman becoming a professional artist. Born in 1901 to a poor Jewish couple, living at 79 Lower Chapman St, Stepney, who had emigrated to the East End of London from Russia, Barnett’s childhood was scarred by ill-health and he was confined to bed between the ages of nine and thirteen. Yet he educated himself, learning to read, write, play music, draw and paint, all within a hospital ward. His nephew, Norman, recalled that “He played the violin for the king,” but that “When he acquired a bicycle his mother cut off the tyres as she considered it too dangerous for her son to ride.”

By sixteen, Barnett was earning his living as a draughtsman to a monumental mason for a few shillings a week. He made the best of this unexciting work in the day, spending his evenings at St Martin’s School of Art for five years from 1917. Eventually, he moved to an architect’s office, working up his employer’s rough sketches and, during a surge of war memorial work, honing his skills as a lettering artist.

For three successive years, Barnett failed to win a London County Council Senior Scholarship in Art that would enable him to study full time at the Royal College of Art under the direction of William Rothenstein. Finally, Barnett presented a portfolio of work to Rothenstein in person. Impressed, he put Barnett’s case to the London County Council Chief Inspector himself and a stipend of £120 a year was made, enabling Barnett to begin his studies in 1922. Under the direction of Rothenstein, Barnett’s talent flourished, taught by such fine draughtsmen as Randolph Schwabe and stimulated by fellow students Edward Bawden, Raymond Coxon, Henry Moore, Vivian Pitchforth and John Tunnard. Eight years after his entry, Rothenstein took Barnett onto the staff.

Although he could be prickly and even alarming on occasion, Barnett was revered by his former students. My late friends Leonard Appelbee and his wife Frances Macdonald, both artists, never stopped talking of his kindness. Burly Leonard used to help lift Barnett’s heavy lithographic stones when they were too much for the artist to manage alone, and when once Leonard and Frances considered moving to Hampstead, Barnett retorted – “You don’t want to go there. It’s an ‘orrible place!” According to Professor Rogerson, “He was a volatile character who did not respect authority and was always at war with the civil servants … yet I know people who were taught by him who say he was a very careful and punctilious teacher who paid a lot of attention to his students – though he could fire off if he was angry. At heart, I think he pretended to be a harsh kind of person but he was very good to a lot of people.”

After leaving the Royal College in 1925, Barnett had his share of problems. He painted prolifically but sold little – with his work only gradually being bought by collectors, although the Victoria and Albert Museum and Contemporary Art Society eventually bought drawings. In 1929, ill-health prevented him from working for a year. In 1930, he married Claudia Guercio whom he had met at art school, born in Lancashire of Sicilian ancestry. She also became a fine illustrator. Their son Vincent recalls that the home they created “was a warm place, vibrant with sound and brilliant colours, excitement darting from the music at night, the pictures on the walls, and the constant talking.”

Barnett enjoyed a long association with Faber and Faber, and his colour lithography and black-and-white illustrations for Siegfried Sassoon’s ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer,’ published in 1931, are outstanding. Works by the Brontë sisters, Walter de la Mare, Charles Dickens, Edith Sitwell, William Shakespeare and Leo Tolstoy benefited from his inspired illustration. Barnett believed that “the art of book illustration is native to this country … for the British are a literary nation.” He argued that “however good a descriptive text might be, illustrations which go with the writings add reality and significance to our understanding of the scene, for all becomes more vivid to us, and we can, with ease, conjure up the exact environment – it all stands clearly before us.”

He was also an outstanding commercial designer, producing a huge output of work for clients including Ealing Films, the General Post Office, Curwen Press, Shell-Mex and British Petroleum, Josiah Wedgwood and London Transport. The series of forty lithographs by notable artists for Lyons’ teashops was supervised by Barnett, including his famous and beautiful auto-lithographs ‘People’ and ‘The Window Box.’ Barnett wrote and broadcast on lithography and other aspects of art, with surviving scripts showing him to have been a natural talent at the microphone. When artists were being chosen for the series ‘English Masters of Black-and-White’ just after the Second World War, the editor, Graham Reynolds included Barnett among an illustrious band alongside George Cruikshank, Sir John Tenniel and Rex Whistler.

Barnett joined that select group who served as Official War Artists. Along with Edward Ardizzone and Edward Bawden, he accompanied the expeditionary force in the spring of 1940, before the retreat at Dunkirk, yet Barnett did not shed his iconoclasm and outspokenness when he donned khaki. Asked if he would paint a portrait of the legendary General Gort, General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Barnett’s response was, “I am not interested in uniform … Oh well, perhaps I might if he’s got a good head?” On his return, Barnett continued to produce vivid, powerful pictures for the War Office and the Admiralty, gaining a CBE in 1946. But despite hobnobbing with military luminaries, Barnett never became posh, retaining his East End manner of speaking. Vincent Freeman recalls how Barnett once hailed a taxi-cab, “‘to the Athenaeum Club’, to which the incredulous driver retorted – ‘What, YOU?'”

After hostilities, Barnett remained busy with many commissions until in 1958, when he died peacefully in his chair at his Cornwall Gardens studio, near Gloucester Rd, aged only fifty-seven. Vincent recalls his final memory of his father, “discussing a pleasant lunch he had enjoyed with the family’s oldest friend [the artist] Anne Spalding.” Barnett was widely obituarized and his work was given an Arts Council memorial exhibition and tour. Subsequently, exhibitions such as that at Manchester Polytechnic Library in 1990 and new books have periodically enhanced his reputation.

Barnett Freedman is among my top candidates for a blue plaque, as one of the most distinguished British artists to emerge from the East End. There was a 2006 campaign to get him one in at 25 Stanhope St, off the Euston Rd, where he lived early in his career, but English Heritage rejected him, along with four others as of “insufficient stature or historical significance” – an unjust decision exposed by the Camden New Journal. The artist and Camden resident David Gentleman was one among many who supported the plaque, writing “He was a very good and original artist whose work deserves to be remembered. He influenced me in the sense of his meticulous workmanship. He was a real master of it.”

Professor Ian Rogerson, author of ‘The Graphic Work of Barnett Freedman’, considers Barnett “the world’s best auto-lithographer … A lot of people who do not seem to have contributed as much to the arts have managed to get blue plaques. Freedman’s work is being increasingly collected – and he is being recognised more and more as a major contributor to British art.” Of Barnett’s remarkable output, his son Vincent says – “A huge optimism and compassion shows itself to me in all his work and life. Humanity was his central driving force.”

![01Fam Portrait]()

Freedman family portrait with Barnett standing far left.

![6]()

Barnett painting on the roof top as a war artist

![B and C Freedman in front of Gun Turret]()

Barnett shows his wife Claudia a mural he painted as the official Royal Marines artist.

![Dad BBC Feb 1939]()

Recording the BBC ‘Sight & Sound’ programme ‘Artists v Poets’ in February 1939, Sir Kenneth Clark master of ceremonies with scorer. Artists from left: Duncan Grant, Brynhild Parker, Barnett Freedman, Nicolas Bentley, and poets – W. J. Turner, Stephen Spender, Winifred Holmes and George Barker.

![Dad Fishing]()

Barnett enjoys a successful afternoon fishing at Thame, Buckinghamshire, in the thirties.

![london ballet001]()

Designs for the ‘London Ballet.’ (courtesy Fleece Press)

![windowbox001]()

The Window Box, lithograph.

![Barnett Freedman Underground]()

Advertisement for London Transport from the nineteen thirties.

![epsom summer meeting001]()

![Underground 1936001]()

![telephone less001]()

Advertisement for the General Post Office rom the nineteen-forties.

![telephone less002]()

![festival of britain001]()

Advertisement for Shell at the time of the Festival of Britain, 1951.

![ealing001]()

Design for Ealing Studios.

![memoirs of an infantry officer001]()

Cover for ‘Memoirs of a an Infantry Officer,’ Faber and Faber.

![tribute to walter de la mare001]()

Cover for Walter de la Mare’s 75th Birthday Tribute, Faber and Faber.

![baynard claudia001]()

Barnett Freedman’s ‘Claudia’ typeface.

![dartington hall cider001]()

Design for Dartington Hall, Devon.

![Oliver Twist 004]()

Lithographs for ‘Oliver Twist,’ published by the Heritage Press in New York, 1939.

![oliver twist001]()

![Oliver Twist 003]()

![oliver twist002]()

![oliver twist003]()

![Oliver Twist 001]()

![oliver twist004]()

![Oliver Twist 002]()

Barnett Freedman works courtesy Special Collections, Manchester Metropolitan University

Barnett Freedman is featured in my book East End Vernacular, Artists Who Painted London’s East End Streets in the 20th Century

![9780995740112]()

Click here to order a copy of EAST END END VERNACULAR for £25

![BGX05 [1110] mesolithic flint adze length 139mm](http://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/050.jpg?resize=600%2C247)

![BGX05<389>[1327] Post Med Ceramic Tobacco Pipe pop fig 107 Admiral Vernon](http://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/0221.jpg?resize=600%2C706)

![BGX05<389>[1327] Post Med Ceramic Tobacco Pipe pop fig 107 Admiral Vernon](http://i2.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/022_22.jpg?resize=600%2C711)

![HLW06 Stone alleys CW from rear <134><133><132>[3000]<138>[4075] diam <132>15mm](http://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/0392.jpg?resize=600%2C405)

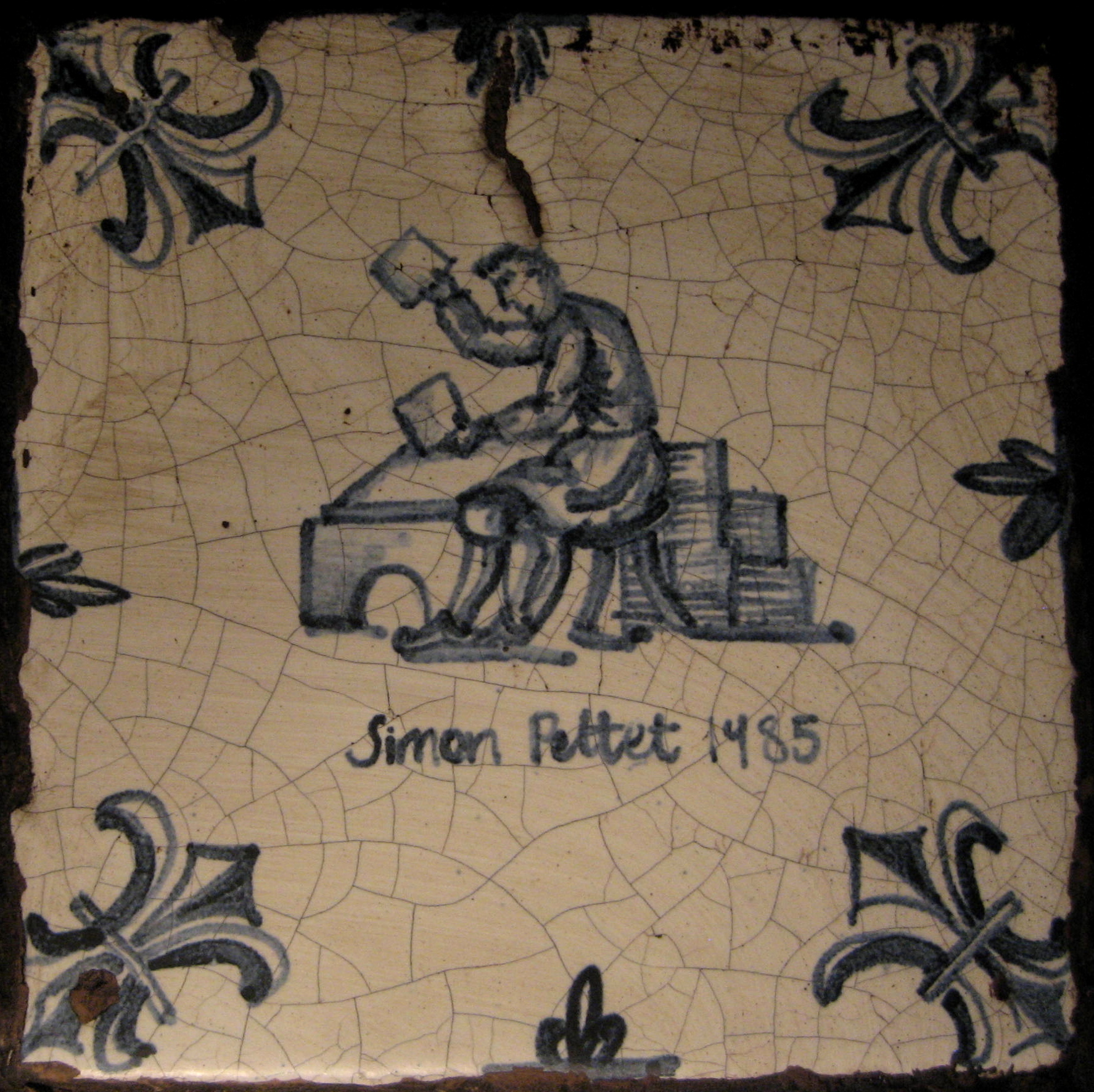

![BGX05 [2050] <1278> Ceramic wall tile](http://i1.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/024.jpg?resize=600%2C540)

![BGX05<680>[617]<173>[+] Post Med Wall Tiles](http://i2.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/051.jpg?resize=600%2C910)

![BGX05 [+] <161> Ceramic wall tile post med](http://i1.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/026.jpg?resize=600%2C603)

![BGX05 [2050] <1266> Ceramic wall tile post med](http://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/027.jpg?resize=600%2C578)

![BGX05<1534>[711] Post Med bone figure](http://i1.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/049.jpg?resize=600%2C2193)

![BGX05<1179>[2087] Cu Post med](http://i0.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/035.jpg?resize=600%2C275)

The Pope

The Pope

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Councillor or Magistrate

The Porter

The Porter

The Miser

The Miser The Gamesters

The Gamesters